Carroll William Westfall

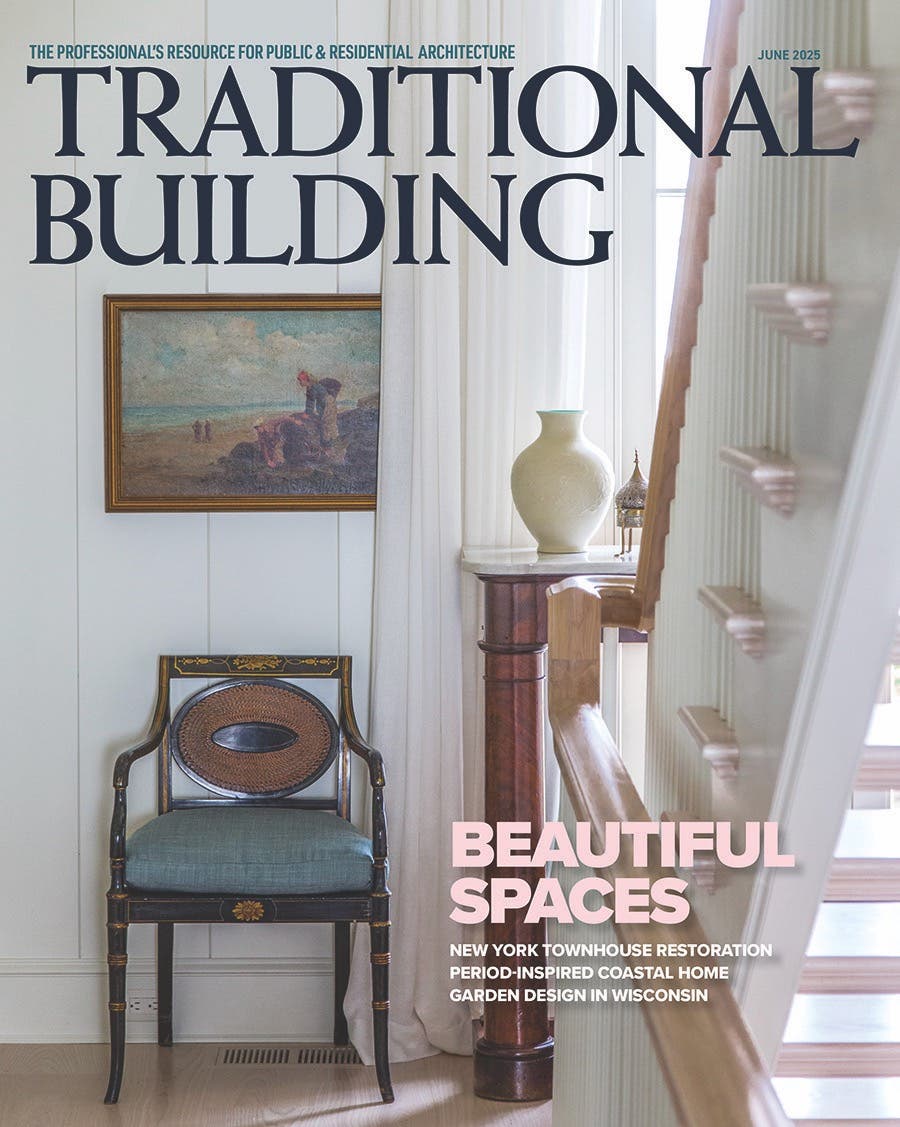

Does Anyplace Teach Architecture Anymore? Part 3

“They don’t teach architecture here anymore,” Emeritus Professor Howard Moise told me in 1957 in one of my three semesters as an architecture major at the University of California, Berkeley. Established in 1903, it had recently instituted the Bauhaus program to replace the one based on the École des Beaux Arts. What is taught there and elsewhere now?

Design. They teach design.

In Part 2 we saw that design entered architecture-talk during the Renaissance as the middle term in the architect’s movement from purpose to be served to design as drawings that guided construction in building a beautiful building that serves and expresses its purpose. Architecture was allied with the liberal arts to serve the political order with buildings representing the varying importance of their purposes in serving the common good. In designing, the architect’s designs drew on precedents and experience transmitted by tradition and used reasoned deliberation to adapt to new circumstances and contribute to the urbanism they joined.

Now we turn what is taught and practiced in architecture today. It is the Modernism in its many styles that flow from the Bauhaus program. Walter Gropius described it in The New Architecture and the Bauhaus in English in 1935, two years after Hitler closed that school and its faculty dispersed. The reasoning, intentions, and instructional methods described nearly 80 years ago now dominate the culture of architecture—in curricula and criticism, in histories and practices, and in professional and general architecture-talk.

At its heart is the concept of design, no longer meaning merely the drawings used in constructing a building serving and expressing an institutional purpose. Instead, a design leads to the encapsulated “authoritative significance… that men achieve by working “independently, although in close cooperation, to further a common cause …” and “like human nature, should be all-embracing in its scope.”

Design is to be creative and void of all precedents. In architecture, “the morphology of dead styles has been destroyed; … we are returning to honesty of thought and feeling.” (19)

Design is omnipresent in architecture-talk, and so is the word influence justifying and explaining designs that are “simply the inevitable logical product of the intellectual, social and technical conditions of our age.” As historians explain it, the influences of the Zeitgeist produce the styles distinctive of the succession of eras leading from pre-civil ages to the present.

With traditions and precedents dismissed, control in designing moves to the influences of the present and the instincts that reside in human nature. To let them flourish, eighteen year old students are given the opportunity “to acquire that personal experience and self-taught knowledge which are the only means of realizing the natural limitations of our creative powers … [and] give tangible shape to their own creative instincts.”

In the purpose to design to construction process, design is in command. Purpose would serve efficiency with disregard for the common good, and construction would use new materials and technologies entrusted to a small elite that “will know … how to make industry adopt their improvements and inventions [and] …make the machine the vehicle of their ideas” (86).

Two fundamental traditional links are severed. First, whether built for public purposes or for private uses, a building is no longer a public object partnered with the liberal arts’ contribution to the common good. Instead, it is a fine arts object like a painting or sculpture, a Ding an sich, a private, creative expression inescapably displayed in public. Thus liberated, “A modern building should derive its architectural significance solely from the virgour and consequence of its own organic proportion, … logically transparent and virginal of lies or trivialities, … a direct affirmation of our contemporary world of mechanization and rapid transit.”

Second, “But what about beauty?” Beauty within the equation of beauty and utility is banned as “a florid aestheticism, as weak as it was sentimental.” Utility as an aesthetic survives “in diametrical opposition to that of ‘art for art’s sake’.” Ponderous, earth-hugging buildings give way to “simple and sharply modeled designs … [whose] “aesthetic meets our material and psychological requirements alike … [with] concrete expression of the life of our epoch … in clear and crisply simplified forms.”

Gropius defended his program against claims that it is obsessed with mechanistic technique, blindly seeking “to destroy all deeper national loyalties,” and “doomed to lead to the deification of pure materialism.” No: it is based on his “thorough and conscientious series of investigations.” It runs counter to current needs and demands. No. “The necessity of the New Architecture can no longer be called in doubt. And the proof of this … is that in all countries Youth has been fired with its inspiration.” And it undermines the German spirit and tradition. And no. His personal lineage from Prussian architects is in “the tradition of Schinkel;” in earlier pronouncements he had argued that it extended Germany’s architectural traditions.

Other opponents included Nazis who others who added that it was communist, bolshevist, socialist-inspired, or aligned with the radical parties opposing the Weimer Republic.

Its flat-roofed, strip-windowed, white, urban complexes (1) were unsuitable for Germans who wanted pitch-roofed family houses with kitchen gardens. (2: 3)

The Nazis gained control and in 1933 closed the Bauhaus and initiated a vigorous building campaign with the various Nazi officials building in progressive versions of traditional styles while Hitler used Albert Speer for large, indubitably monumental classical buildings serving and expressing his totalitarian schemes.

Gropius’ new architecture was imported to America through the Museum of Modern Art founded in 1929 by Phillip Johnson, an aesthete who thrilled to the power of Hitler’s rallies, program, and buildings, and Henry Russell Hitchcock, an enthusiast of Fascism. The vehicle was an exhibition in 1932 with a book, The International Style: Architecture Since 1922. In the United States the term International Style had been bruited about, but the exhibition disentangled it from Germany and offered it as the style of the new, exciting era currently suffering in the Depression. The MoMA’s director Alfred Barr, Jr. supported this avant-garde Modernism that, as Ortega Y Gasset observed in “The Dehumanization of Art,” was for the elite few who could “recognize themselves and one another in the drab mass of society and … learn their mission which consists in being few and holding their own against the many.”

Stripped classical styles and social concerns, becoming visible during the 1920s, grew more prominent during the Depression. At Penn, Paul Cret responded in his studios, and at Cal Moise was hired to calm student agitation. In Chicago in 1937, the former Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy established the Institute of Design, and in 1940 it was combined with the architecture program that Ludwig Mies an der Rohe (the last director of the Bauhaus) had established to form the Illinois Institute of Technology. (As mentioned in Part 1, IIT would supply Cal with faculty.) And also in 1937, Gropius was brought to Harvard from England to chair the Department of Architecture.

With victory in World War II, civilian construction resumed and International Style Modernism quickly achieved dominance. The United Nations Building for the center for progress toward world peace was completed in 1952, the same year as Lever House, a corporate headquarters, and a year after Mies’ 860-880 Lake Shore Drive apartments. Colleges, universities, and cultural institutions soon followed, and so did local school boards. They had formerly built civic monuments to educate a citizenry; now they built efficient factories processing baby boomers. These buildings, whether private or public, were built with other people’s money, securing Modernism’s position among those who valued standing out from the “drab mass of society,” that is, from the many who use their own money to build for their own purposes and, preferring the traditional styles provided by builders, disdain architects’ Modernism.

The glass-box-style of the elite understandably led to ennui that unleashed a parade of new Modernist styles, some playing with the Modernist canon, others inserting caricatures of earlier styles or expressing nihilism, or designed by computers, or simply overdosing with self-satisfied narcissism as “art for art’s sake.” This is hardly surprising their instructors and models were former eighteen year olds had emerged from professional training at schools like Cal’s whose current website calls it “one of the world’s most distinguished laboratories for experimentation, research, and intellectual synergy… skilled professionals to help craft built environments [their] teachers cannot yet conjure.” (4)

Or Harvard (5):

“Today’s graduates in architecture continue this tradition by pioneering new design approaches to the challenges posed by contemporary society.” Or IIT (6):

Here “resourcefulness and daring are rewarded. We are committed to helping our graduates become exceptional design leaders as well as ethical global citizens.”

Absent is the commitment to a profession that defined an architect in 1906 as a “man of general culture with special architectural abilities.” Now the architect is a person whose designs are, as Gropius had hoped, the “logical product of the intellectual, social and technical conditions of our age:” indeed that, and no better than that.

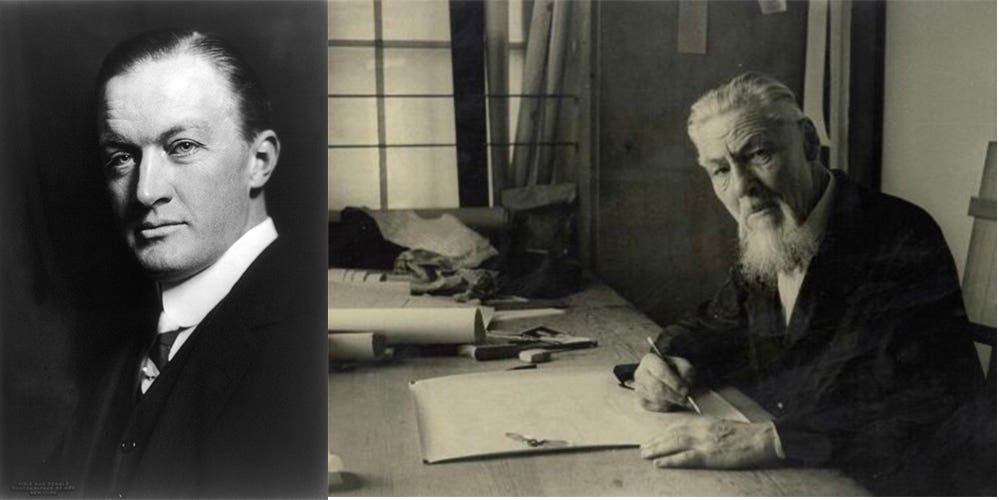

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.