Carroll William Westfall

Does Anyplace Teach Architecture Anymore? Part 1

“They don’t teach architecture here anymore.” So said Emeritus Professor Howard Moise in 1957 at the Beaux Arts Ball in one of my three semesters as an architecture major at the University of California, Berkeley.

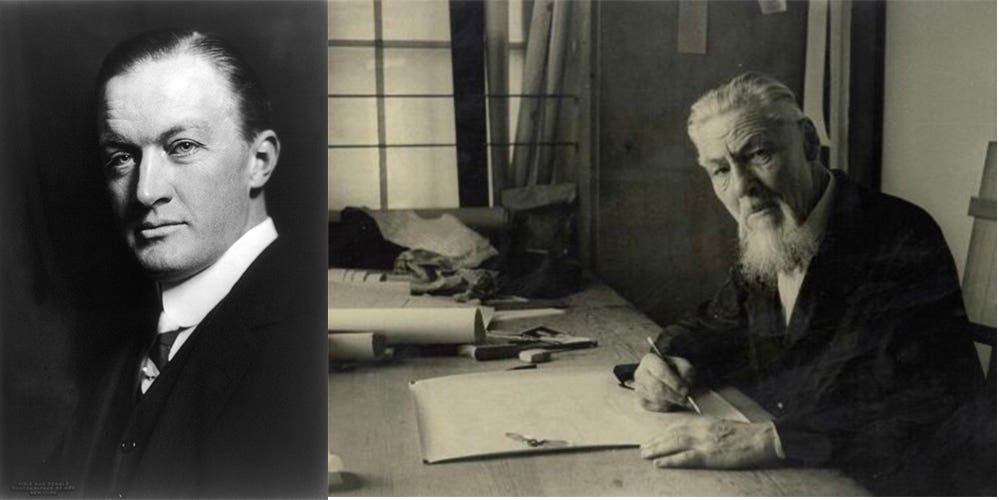

It was held in “The Ark,” the school’s beloved redwood home constructed in 1906 by John Galen Howard (1864-1931). After studying at the École des Beaux Arts Howard had worked for Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge and for McKim Mead and White before founding Berkeley’s Beaux-Arts program in 1903, the nation’s 13th., and populating the university and its region with his buildings.

Howard’s program had slackened before he was replaced as Dean in 1927 by Warren Perry (1884-1980), a Berkeley graduate with two years at the École and a faculty member since 1911. The professional periodicals had whetted students’ appetites for stripped, modern classical styles, but the Dean and faculty were unresponsive. As the economy floundered the students became adamant and disruptive, and in 1932 Perry hired Moise to steady the ship. A Harvard graduate working for James Gamble Rogers, he preferred the Gothic, was a solid designer who also taught history and theory, and was charming and much liked. He responded to students, gradually loosening the Beaux Arts rigors and adding attention to housing and planning.

Moise, who would retire in 1955, argued vehemently for including sociology in the curriculum, but in 1940 he apologized to Perry for having grown "closer to the modern student who is certainly unhappy, disillusioned and worried about what the future holds for him." Those students’ post-war successors, even more distressed, appealed to the university president and pounded on Perry who offered to resign as Dean but continuing to teach design and history until 1952.

In 1950 William Wilson Wurster (1895-1973), a San Francisco native and Berkeley graduate, assumed command. After working in New York and travelling extensively in Europe, he returned to Delano and Aldrich’s office before setting up his own office in San Francisco in 1924. The residences prominent in his oeuvre were low slung with open plans using regional materials and fitting the terrain, as in a 1926 prototypical ranch house.

For Frank Lloyd Wright he was a shanty builder, for others he was Redwood Bill. After the war his thriving practice, Wurster, Bernardi, and Emmons, produced some famous Case Study Houses and Modernist commercial buildings.

Wurster had familiarized himself with Scandinavian and other Modernisms while travelling in 1937. In 1940 he married Katherine Bauer, a leading housing advocate, enjoyed a year’s fellowship at Harvard in 1943 followed by a year teaching at Yale and in 1944 appointed as Dean at MIT. He gathered a diverse, high-quality faculty, added planning and the social sciences to the curriculum, made connections with other MIT resources, foreswore doctrine, stressed student involvement, and substituted the open juries universally used today after ending sending student work to the closed juries of the Institute of Beaux Arts Design in New York.

At Berkeley, he transformed the troubled program. He instituted the five-year BArch, collected a diverse faculty, brought in notable visiting faculty, and initiated planning for a new architecture building.

He replaced the Beaux Arts’ master-pupil surrogate or apprenticeship, instead offering a smorgasbord of diverse views along with the university’s liberal arts requirements.

When I arrived the previous program’s last remaining students were producing beautifully rendered projects such as a “Monument to Joan of Arc.”

Their history lectures offered a march through the styles documented in Sir Banister Flecher’s History with its famous “Tree of Architecture” with G.W.F. Hegel’s goddaughters personifying the six influences lounging underneath. Also prominent was Julien Gaudet’s Elements and Theories that ignored stylistic changes while providing grist for the Beaux Arts mill.

In 1952 Wurster hired the school’s first person to teach history who was not trained as an architect. James S. Ackerman (who would leave for Harvard in 1960), another San Franciscan, had studied the discipline of architectural history imported by German refugees. In his required survey the texts were Pevsner’s slim 1957 documentation of Modernism’s inevitability in the 5th edition of An Outline of European Architecture with its “American Postscript” and Geoffrey Scott’s The Architecture of Humanism that offered critical assessments for buildings.

The College’s “Announcement” laid aside the idea held by “some architects … for whom a building is almost wholly a personal work of art, quite removed from the practical world.” The architect must work joyfully with clients to build something practical, enduring, “an integral part of the community environment and the civic scene,” a citizen and skilled professional craftsman, in a career “interwoven with history but with infinite care that it is neither only a reflection of the past nor the move to the new for its own sake.”

This translated into addressing social purposes and suitability to the present time, place, and materials. Form followed function, each one new and unique calling for a new, inventive design at the leading edge of the ongoing march of styles. When I was learning about that march I asked Dean Wurster on a Friday afternoon when he met with students in the “The Ark’s” courtyard how he would characterize the style of the buildings, old and new, on Berkeley’s handsome campus. His reply: “Each the best of its year.”

My fellow 18-year-olds had come to learn how to become architects from those who knew, but we were instead being taught to become designers by drawing designs out of ourselves.

Our first year courses were taught by two non-architects. James Prestini, who held two Yale degrees (mechanical engineering and teaching), was a master craftsman in wood and metal hired in 1956.

He had been a student at University of Stockholm in 1938 and in 1939 a student of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy at IIT where he befriended Mies van der Rohe and designed furniture for Knoll International. After spending three years in Italy he arrived at Berkeley where he would establish a “design laboratory” or shop for experimental research in Berkeley’s new architecture building before retiring in 1975.

Wurster had hired him in 1956 on the recommendation of his former IIT student Jesse Reichek whom Wurster had hired in 1953 on the recommendation of MIT’s Gyorgy Kepes. Gaining fame as a painter of abstract works, his career had included study with Serge Chermayeff at IIT’s predecessor, the army, four years in Paris with a nominal affiliation with the Academy Julian and a diploma in 1951, then IIT with Chermayeff having him head the basic design curriculum. He retired from Berkeley in 1986.Here are their course descriptions: First semester: “1N: Exploration of tools and materials: study of line, plane, color, texture, tone, visual relations and physical structures. Time about equally divided between drafting room and shop.” The second semester, also six hours: “2N: Continuation of 1N, with emphasis on the study of space, scale, form, environment, motion, light. Introduction to basic needs of man, space requirements for human functions, and circulation patterns.”

Courses like those remain embedded in architectural education. Here is Virginia Tech’s current year-long introductory course: “Foundation Design Lab is an immersive, interactive learning environment focused on inquiry, experimentation, discovery, and synthesis for students studying architecture, landscape architecture, interior design, and industrial design. The design lab develops self-reliance and self-critique, opens intellectual horizons, and challenges students to continually expand and deepen their aesthetic judgement and critical understanding.” Nothing there about the art of architecture. It was all about having students invent unprecedented designs for things.

Class time involved not instruction but discussions about our designs. Examples: Purchase a broad range of materials that make marks and use them to make examples of “line, plane, texture,” etc. Make a cube using illustration board perfectly 4 inches on a side. It was then tested with a carefully constructed wooden matrix for snug fit and no wobble. Remove a face of the cube and insert one of two identical objects, say, a ping pong ball, and treat the cube’s interior in a way that made it appear different from the one not inserted. Enclose a transparent volume 36 square inches in plan and six inches high that will sustain a weight on its top using the least material weight relative to the supported weight. In the shop make a solid piece of wood flexible.

Beaux-Arts students were taught how to made a building within an art of architecture serving and expressing a commitment to the common good with beauty allied with predecessors within a local or national tradition. Instruction in architecture now concentrates on design as a medium for personal self-indulgence. Nonetheless, there is an increasing presence of traditional building and architecture in practice and expanding opportunities for instruction in the art of architecture as a public, civic good, most notably at Notre Dame.

In later contributions I will discuss what has been lost and what is being offered in education in architecture. Read Part 2, Part 3.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.