Carroll William Westfall

A Factory Building Wearing a Dickey

The most common classical building is a box dressed for the occasion its purpose serves. For very important purposes, it needs formal dress, and a temple-front can serve as a dickey. Andrea Palladio dressed boxes with dickeys for the rural villa dwellings he built for some of the Venetian upper class whose dwellings in Venice were palaces but who lived in the countryside when superintending their rural estates.

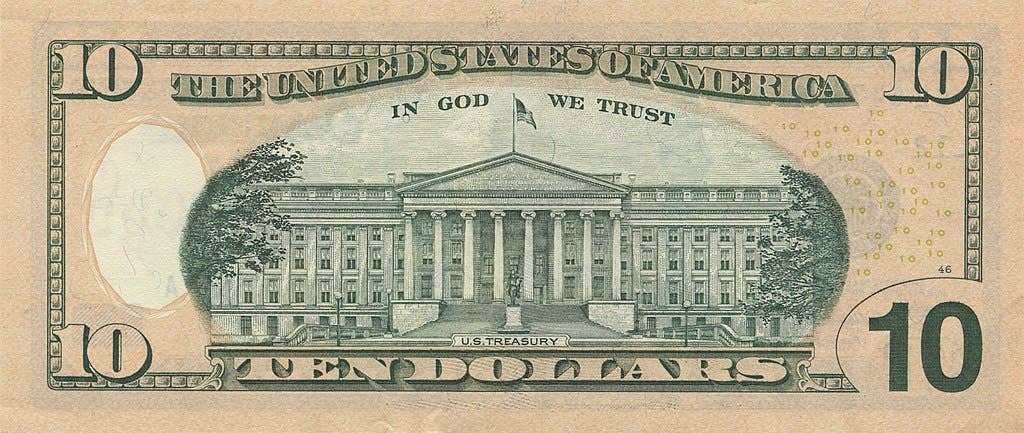

Palladio’s book carried the style of dress to England and then to the new United States where attaching a temple front to a box became common practice for the most important federal buildings: James Hoban’s’ White House, Robert Mills’ Treasury, and much later, Cass Gilbert’s Supreme Court and finally the streamlined, proto modernist Federal Reserve Building by Paul Cret. In these, the dickey declared, “Something important happens here!”

Why, then, do we find something like it on the façade of a mere factory building built in 1916 or 1921? The former Cussons, May and Company, 715 Bowe Street, Richmond, Virginia was founded by John Cussons an English immigrant, Confederate veteran, and outspoken defender of the Lost Cause who had died in 1912. It contributes to a small National Register district of brick industrial buildings. To the north is a now revitalized Jim Crow neighborhood trashed by an elevated interstate highway that separated it from the HBCU Virginia Union University. To its west was a railroad yard with spurs running into loft buildings now replaced by a Lowes and a small supermarket and parking lot facing this factory across a narrow street. In its hypostyle timber post and beam were printed advertising calendars, blotters, and labels for medicine and wine bottles used throughout the country; now it holds three apartments.

Its three bay, three story façade, now liberated and easily seen, has a two story, two bay, recessed extension and runs six bays deep along the alley whose facade is like the extension’s.

The principal façade has a three layer classical composition that it wears like a dickey. The first layer is a knee high podium that supports four pilaster-like panels, each one four bricks wide, rising unbroken to capitals suggested by three slightly projecting courses. These “pilasters” carry an “entablature” of seventeen courses, some of them headers, laid with three series of recessions and projections suggesting the architrave, frieze, and projecting cornice, with pairs of bricks suggesting acroteria aligned with the pilasters.

The next layer is the wall rising from the podium’s canted headers. Two bricks show on each side of each pilaster. In each bay on each floor were 4 over 4 wooden sash windows, now replaced. Soldier courses suggest lintels, and canted header courses suggest sills. Running beside the fenestration from the lowest windows’ sills are face bricks casting distinct shadows and meeting the entablature with a stone or concrete block. Four of the nine windows are slightly different: In the middle bay of the second story and in the three ground floor windows the sill sits atop soldier courses; they also lack the let-in panels below the other five windows. Its absence above the middle ground floor windows gives a slight emphasis to the block’s center.

The only ornamentation is above the portal in the two bay office/entrance attachment. It is surmounted by an assembly of corbels, lintel, abbreviated entablature, and pedimented constructed with cast stone and lacking incising or profiles.

This membrature, derived from the classical apparatus forms, is a minimalist sketch that relates the factory to buildings of much higher rank such as Thomas Jefferson’s Capitol not far away. It can become the Supreme Court Building by adding a pediment, substituting marble for brick, using a free standing Corinthian order rather than the Doric and eight rather than four with the central pair set slightly farther apart with another row behind, putting it above a flight of stairs and in front of an impressive entrance porch, adding ornamental enrichment, extending long wings that are set further back on both sides with pilasters between tiers of basement and tall windows, and placing it in a landscape setting rather than across from a Kroeger parking lot.

Both the sketch and the top ranked version have, for thousands of years, connected people with the world and with others living in it. Those meaningful connections are part and parcel of experiencing classical buildings, and have been ever since the finest that classical architecture was able to produce has been used to serve and express their highest purposes and aspirations. They were crafted by hand to serve the gods and whatever else deserved the best, such as EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW. That connection between architecture and its service to the good life well lived was the invaluable legacy that is classical architecture.

That connection unraveled under the pressures of new roles that buildings were asked to play in the world embracing commerce, industry, technology, and philosophy. The connections earlier that classical theories explained were cast aside was new theories were offered to invest their forms with meanings. In 1914 Geoffrey Scott’s remarkable book The Architecture of Humanism, written before modernism had breached architecture, unmasked the fallacies being used to justify building designs, dismissing them as notions that inhibited the aesthetic pleasure architecture offered. Disregard them, he urged, and enjoy what you see. “Architecture simply and immediately perceived, is a combination revealed through light and shade, of spaces, of masses, and of lines.” Its coherence satisfies the order that human nature craves and the architecture of humanism supplies. We betray that aesthetic experience when we substitute “secondary and encircling interests.”

In the half century that followed, modernist architecture largely banished that architecture from the public realm, but Henry Hope Reed campaigned to keep the classical flame alive. In 1954 he published The Golden City, and in 1974 he saw to the republication of Scott’s book. In its Forward Hope stated, “The direct physical reaction to what we see Scott called taste, ‘the disinterested enthusiasm for architectural form’.”

Hope lucidly distinguished taste from fashion, but he left the appreciation in the aesthetic realm without extending it into the meaning and content that classical architecture carries as it connects us to one another and to the world we live in, a role that is neither trivial nor disinterested.

In classical buildings we see what is admirable and valuable in others, in ourselves, and in our activities, connections that are lacking in modernist architecture’s focus on creativity, dependence on technology, and on wizardry of construction. The columnar orders, for example, have long been seen metaphorically as the ancient gods and goddesses and personifications of the sacred, of justice, of power, and of authority in our lives, qualities embodied in the trust we entrust to the Supreme Court and can see in courthouse and in other important public buildings throughout the land. Meanwhile, in this lowly factory we might see the pilasters as the blue-shirted workers, people who enjoy personal dignity and are empowered to participate in the nation’s consequential affairs. In the building’s physical fabric, something carefully crafted in brick and mortar, we are reminded of the importance of those who labor with their hands even as those who labor with the head are more highly regarded and rewarded. And in its classicism were are connected with its workers, with the city and our nation, and with traditions running back to ancient Greece that use the best possible classical architecture to serve the highest purposes and now, in this country, commits itself to equal dignity and justice for all.

It also connects our current moment with all of our forebearers in a tradition of building that adapted and modified what tradition transmitted, using common materials such as bricks and timbers and now cast iron connections in the hypostyle and cast concrete for the portal head. This unite us to the building in a way that the construction of a recently built factory does not. Its materials, extracted from the earth with human labor and skillfully shaped and placed in the construction, allies it with immemorial construction while also easily accepting the modern materials for the windows and the portal head.

Sporting a dickey is not enough to admit this factory to the rarified status that its betters occupy, but it continues to serve. Its presence reminds us that urbanism is constantly amended and that well-built, handsome buildings adaptively reused serve the sustainability that the common good requires. Formerly a humble but steady worker as a factory, it is now a dwelling that continues, more visibly now then formerly, as a handsome presence in the urban realm.

In my previous post I included a drawing that I said was by Sanford White showing his three new buildings at UVA connected by a pergola, and I noted that unfortunately the pergola was built to a lower height; it is, however, the height shown in the MMW monograph.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.