Carroll William Westfall

Does Anyplace Teach Architecture Anymore? Part 2

“They don’t teach architecture here anymore,” Emeritus Professor Howard Moise told me in 1957 in one of my three semesters as an architecture major at the University of California, Berkeley. Established in 1903, it had recently instituted the Bauhaus program to replace the one based on the École des Beaux Arts. What did it teach?

It taught students to do what architects had always done, which is to design beautiful buildings to serve and express the purposes of the political order. They learned their art through experience on building sites and apprenticeships with architects who used the art of architecture to elevate the art of building to the higher standards required for the most important buildings.

The oracle at Delphi’s pronouncement, “The most just is the most beautiful,” applies to individuals and to their political bodies as they pursue lives lived honorably, justly, and well. In doing so they engage in the liberal arts, the arts that a free people use in governing through authoritative institutions. The ultimate authority might reside in a god or gods as a theocracy with secular affairs vested in one person as monarch, several as oligarchs, or the body of citizens in a democracy. In these names, the term arch refers to primary or most important, the role it plays in archi-tect-ure that commands the techne or craftsmanship that fabricates buildings. The art of building is used for all buildings, but the art of architecture elevates that art for the most important ones, the public buildings that serve the most important purposes within the common good. Like the actions of individuals and of cities and nations, all buildings wear a public aspect even those serving private purposes. The resources used in building them are controlled by the political authority, directly for public buildings and indirectly for private ones..

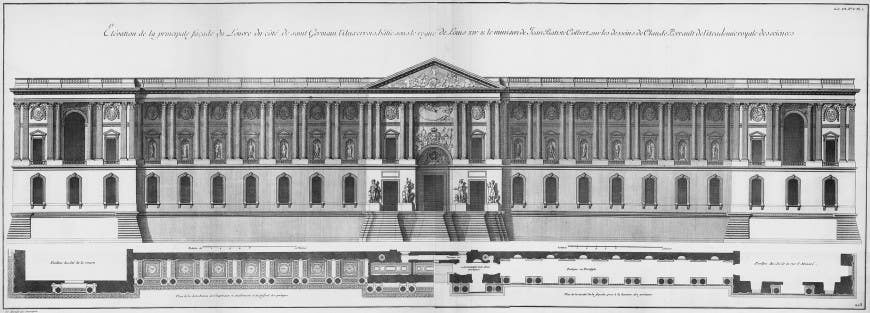

In all political orders the varied purposes are arranged in a graded hierarchy. In traditional societies, the institutions serving religion and public, secular purposes are high on a list that runs on down through residences to trade and manufacturing. Ancient cities built to serve the ancient gods, and Saint Augustine transposed that idea when he define the city of man as the secular host of the City of God, the enduring point made visible in the dominant place churches occupy in traditional urbanism. Augustine’s doctrine would continue well into the Renaissance. It is explicit in Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise that followed Vitruvius’ pairing of reason (ratiocinatio) and technology (fabrica) with the architect’s reasoning intellect producing a design or drawing consisting of lines and angles that control the art of building’s fabrication of material elements and their placement in the building’s composition. This instituted a three step process that moved from a purpose to be served to the architect’s design to serve and express it and ended in construction. The buildings were to be beautiful counterparts to the city’s promotion of the common good. Design, central in architecture and the other visual arts, express, as Norris Kelly Smith noted, “the Albertian belief that there exists an order of things in a lawful universe that possesses the reality and intelligibility of durable stone buildings.” (Here I Stand, 1994, p.158)

This modernized ancient architecture gradually took hold in Italy and France, but in the ensuing centuries its foundations in religion gave way to changed arrangements between church and state and eventually to today’s secularized world.

In late 17th c. France the objective status of beauty was challenged, and in the next century it was separated from being the counterpart of the good. Beauty in buildings had always served as an attribute of power, and now, like power, it came to be understood as variable in different times and places. As a quality in things seen, beauty became a quality relative to the judgment of the eye of the beholder. Its purpose was to give pleasure to the senses, and like the palate’s role in assessing food and wine, the eye’s judgments were called judgments of taste. Experience and education could improve those judgments and expand the pleasure, but the intellect’s reasoning that had formerly been involved no longer was, and beauty’s former connection with morality and the good was severed.

Architecture did, nonetheless, remain firmly planted among the liberal arts, which were absorbing the model of the modern empirical natural sciences in testing received beliefs and doctrines. What was demonstrably false and inefficacious was discarded. Furthermore, in architecture, buildings serving new roles were incorporated into the graded hierarchy—department stores, galleries, factories, railroad stations, multi-story apartment buildings—and deftly fitted into the urbanism.

Tradition still gave architects models that their innovations adapted to serve the new uses and to use the new materials. Treaties, such as Francesco Milizia’s Principi di architettura civile with multiple editions between 1781 and 1875, continued to furnish the history useful for architects. It retained the ancient doctrine of architecture as an art of imitation, but replaced the imitation of “a lawful universe that possesses … reality and intelligibility” with nature’s model of the primitive hut that builders and architects had improved down to his present day. This history was soon replaced by the current genre introduced in 1764. Unconnected to theory, it presented a succession of eras with each producing buildings with distinctive formal characteristics or styles that, with their eras, rise, mature, and decline and obey two rules: one style per era, and, because each new era and style replaced its predecessor, no repeats, but revivals as occurred in the Renaissance were allowed.

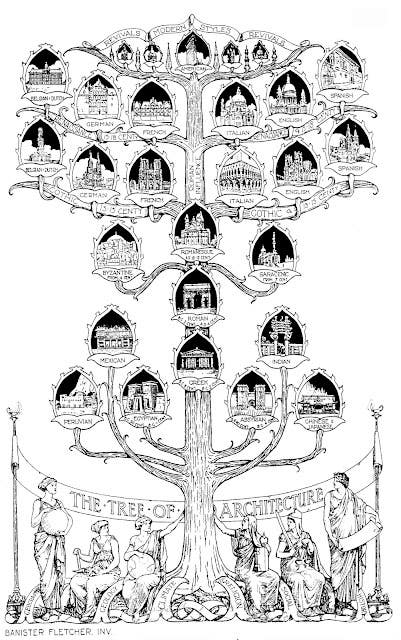

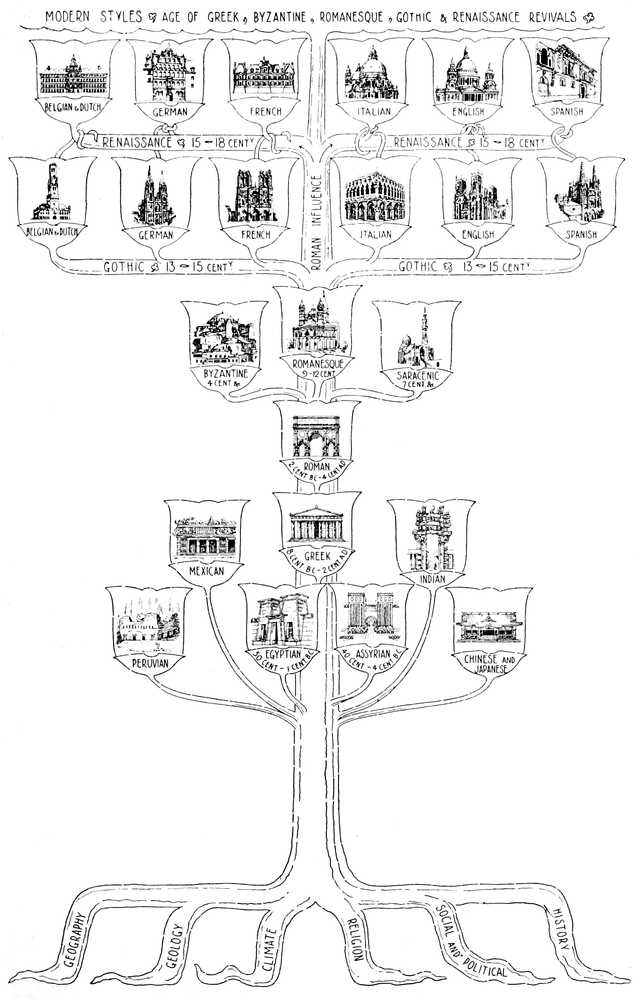

In the 19th c. a secularized idea of progress became the motive force in the narrative. Irresistible progress toward a utopian future was made by a succession of advances that now, in the modern era, was accelerated by modern technology and the natural sciences. In each era, World Historical Figures had captured the era’s influences and produced the culture that included architecture whose style identified the era’s culture. This perfectly closed causative circle is dominant today: The influences of an era’s Zeitgeist produce a style whose style identifies the influence’s era. Bannister Fletcher’s History of Architecture (first ed. 1896) illustrated this progress in 1905 with six influences nourishing the “Tree of Architecture.” The revised “Tree” in the 1921 edition that lavished praise on America’s innovative skyscrapers added a limb featuring D. H. Burnham’s 1902 Flatiron Building.

History and theory now simply ignored the pairing of ratiocinatio and fabrica and the former linkage of beauty and the good. But there were three important survivors. One was the Vitruvian trilogy of firmness, commodity and delight required of all buildings. The second was decorum’s role in policing the graded hierarchy of institutions. And that hierarchy’s survival was the third. Reasoned deliberation superintending ordinatio, dispositio, euythymia, symmetria, and distribution were lost, and beauty remained, but now paired with utility. Its pleasures were now whittled down to the associations carried by borrowed styles in an age of eclecticism. And furthermore, architects continued designing as they always had, by improving on the most recent examples, or the most suitable earlier models, that served or had served similar purposes within a nation’s tradition: Romanesque styles for expressing vigor, Gothic for churches, pre Revolutionary royal buildings for Napoleon III’s empire, ancient buildings for the new American Republic, and so on.

The sequence of purpose to design to construction survived but was given major alterations. Purpose, continuing to be defined by their service to the institutions that built them, now had also to include programs defined by functions and accommodate the “form follows function” formula that Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand had formulated in 1794. It was the genius of the École des Beaux Arts to mesh this with decorum’s policing of design within the graded hierarchy. Another, more consequential modification, immersed construction into the expertise of engineers, which irrevocably separate the art of architecture from the art of building.

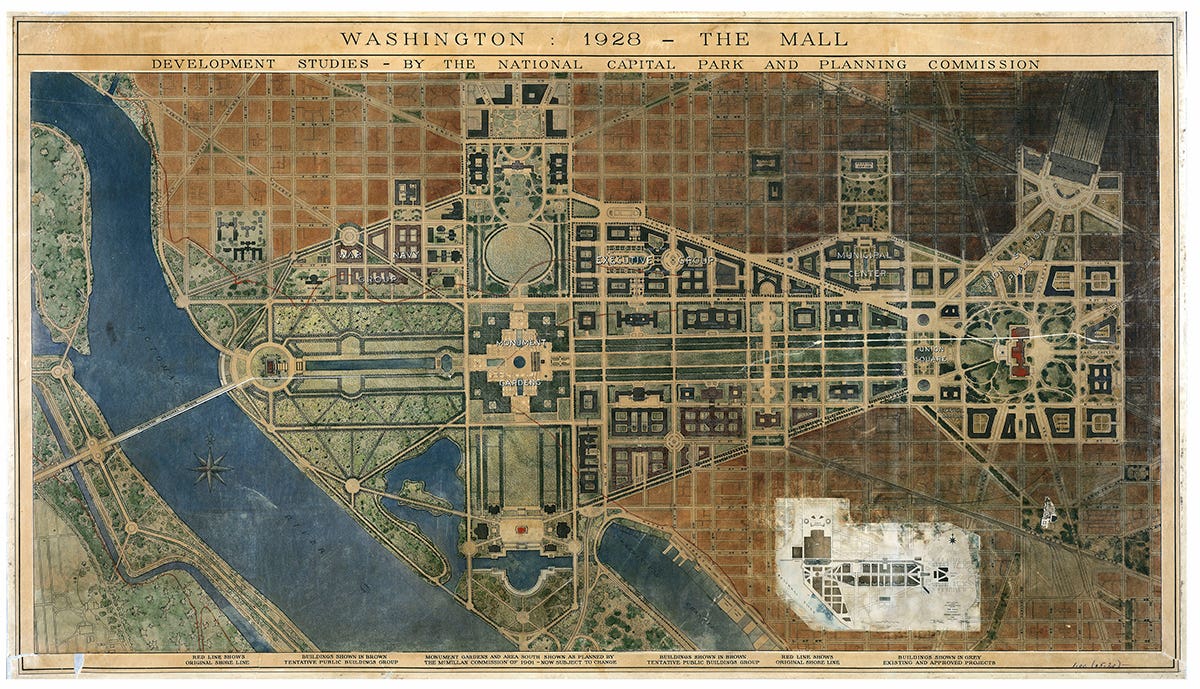

This is the architecture that was imported from the Continent after the Civil War and planted in a novus ordo seclorum, now prosperous and expanding. Buildings would no longer imitate “an order of things in a lawful universe” but instead be entities within a tradition that modernity was modifying but had not yet nullified. They were emblematic of a nation’s order, with its plan of Washington by L’Enfant, Jefferson, and Washington modernized, enlarged and protected by the Capital Planning Commission and its White House, Capitol, and soon-to-be-built Supreme Court finding heirs in towns and cities serving and expressing the purposes of authoritative public institutions, of privately owned corporations, and residential and commercial properties, buildings we love and seek to preserve for posterity.

They were designed by architects when their art was allied with the liberal arts and when the American Institute of Architects in 1906 defined an architect as a “gentleman of general culture with special architectural abilities.” But as Professor Moise said, what they were taught is not taught anymore. What they are taught instead will be the topic of Part 3 of this series.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.