Patrick Webb

Plasters That Play Well Together

For the past couple of years here on Traditional Building Magazine online we’ve been considering the fundamentals of traditional plasters. We began with the basics, explaining what makes something a plaster, where you might expect to find different plasters utilized as well as the practical functions they perform in architecture. Next, we gave an overview of the few simple components making up traditional plasters, paying especially close attention to the chemistry and physical properties of the binders, the “mineral glue” that most influences how a plaster will perform.

Here we take it one step further by mixing things up a little, seeing what happens when we blend certain plaster binders together and identifying which plaster binders play nice together!

Explaining the Diagram

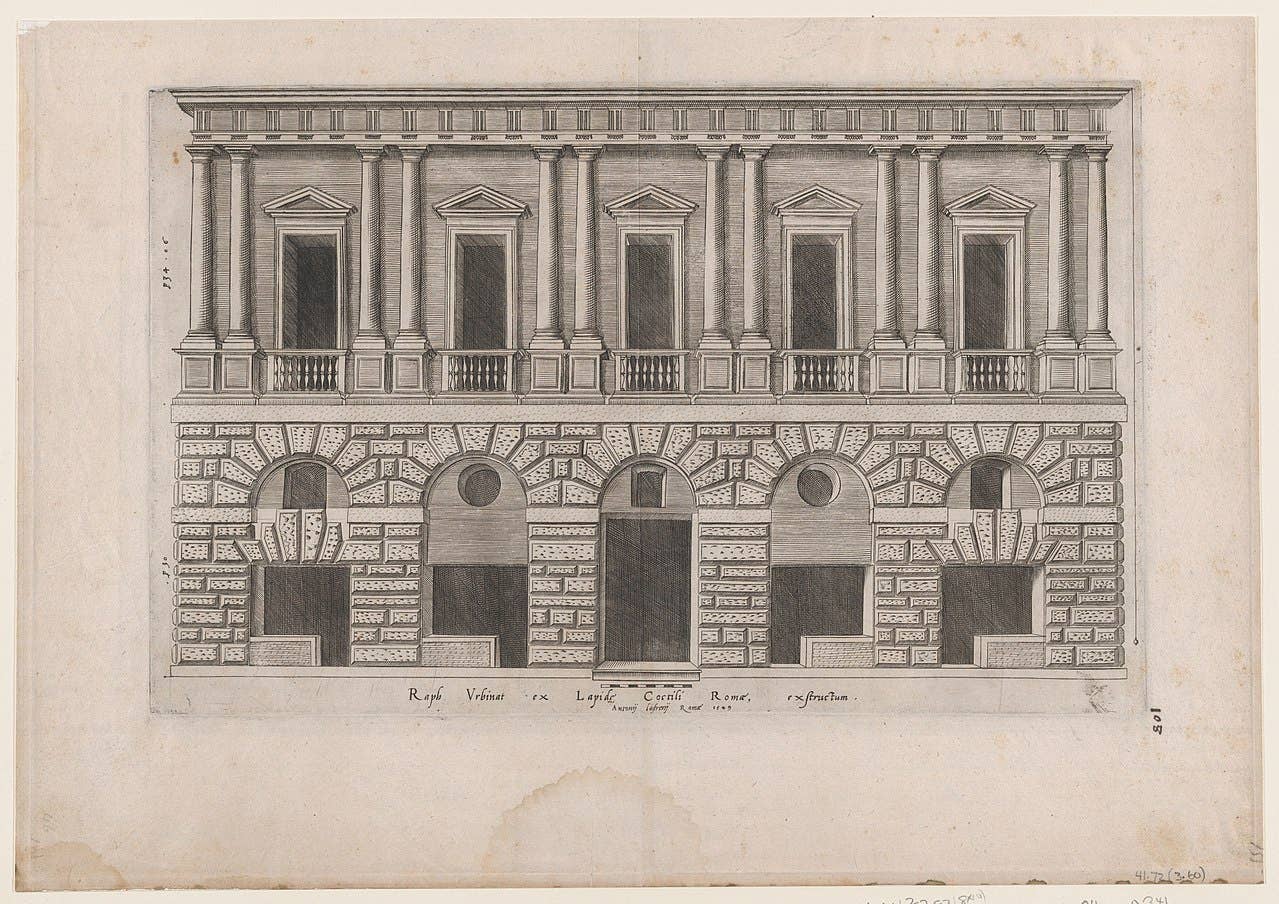

Years ago, when I was studying French plaster traditions in Paris, a local friend and colleague who is a manufacturer of heritage plasters sketched a little useful diagram on a napkin as he was explaining to me which plaster binders were chemically compatible with which. The diagram is used as a basic memory aid that I quickly learned all the plasterers trained with Les Compagnons (the traditional guild system) knew and seemed to almost take for granted.

The diagram is mainly composed of two triangles arranged back to back with a space separating them. As for the triangle at left, above it is Clay, below it is Lime, and to the far left of it is Gypsum. The triangle indicates that any one of these binders may be mixed with any other or even all three together; there being no inherent chemical incompatibility.

The triangle at right is similar. One can blend Clay, Lime and the family of Hydraulic Limes together without an adverse chemical reaction.

However, that is not the case for Gypsum and Hydraulic Limes; they should never be mixed together directly as they will quickly precipitate expanding salts, alternatively known as efflorescence. Hence, the reason for the separation space between triangles. There is one exception. Although hydraulic lime plasters should never be applied over gypsum, it is acceptable to apply gypsum plasters over hydraulic plasters if you wait a full 28 days for the hydraulic component of the lime to cure.

Just because you can blend a binder doesn’t mean you should and not every blend is interesting. However, some blends have proven to be extremely useful extending the aesthetic and performance possibilities beyond any binder used in isolation. Let’s consider a few classic mixes.

Lime and Gauge

Lime plasters are really amazing. They’re the perfect combination of sticky and slick, and the easiest to work up to a perfectly smooth finish. These properties allow the plasterer to apply lime even to the most difficult surfaces such as ceilings with minimal effort.

Lime plaster has a few major drawbacks however. They take a couple of weeks to cure, they always shrink and because of that if you apply them even a little too thick they’ll crack and potentially fail. Plasterers learned that they could “gauge,” that is add gypsum as a minor ingredient to lime and the blended material was still lovely to work with but would set firm in minutes and resist shrinkage and cracking.

Stucco Forte Veneziano

In Venice, there is a tradition similar to lime and gauge but utilizing an opposite ratio; a small amount of lime and marble dust is added to a base of gypsum with a hide glue that retards the set. Because gypsum is self-binding, no aggregates are needed.

The lime makes the blend ductile, perfect for carving in situ and the addition of marble dust allows the blended plaster to be buffed to a high polish. The “stuccotori,” expert Venetians of this medium and technique were highly pursued artisans who carried out grand commissions throughout Italy and eventually abroad to Germany, France and the United Kingdom.

Stabilized Earthen Plaster

Clay based materials such as adobe, cob, rammed earth and earthen plasters are very ecological and inexpensive, requiring no industrial processing and very little if any energy consumption. However, because they are more susceptible to erosion their use has either been limited to very dry climates or require constrained designs with extended eaves to prevent streaming water. However, blending a small percentage of natural hydraulic lime can go a long way in stabilizing an earthen plaster.

While the lime portion stabilizes the clay, the hydraulic component crystallizes around the aggregates. The result is an earthen plaster that retains much of the ecology and breathability typical of clays that can be used in almost any weather environment and with greater architectural liberty.

With a solid foundation in place I think we’re just about ready to progress to the next steps: considering practical specifications for plaster in the contemporary built environment and learning about amazing traditions of working with plaster so that we can set free once again its incomparable aesthetic potential.

My name is Patrick Webb, I’m a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of natural, historically utilized plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime in contemporary architectural specification.

I was raised by a father in an Arts & Crafts tradition. Patrick Sr. learned the “decorative” arts of painting, plastering and wall covering as a young man in England. Raising me equated to teaching through working. All of life’s important lessons were considered ones that could be learned from the mediums of tradition and craft. I found myself most drawn to plastering as I considered it the richest of the three aforementioned trades for artistic expression.

This strong paternal influence was tempered by my grandmother, Geraldine Webb, a cultured, traveled, well-educated woman, fluent in several languages. She made a point of instructing her young grandson in Spanish, French, formal etiquette and opened up an entire worldview of history and culture.

After three years attending the University of Texas’ civil engineering program with a focus on mineral compositions, I departed, taking a vow of poverty, living as a religious aesthetic for a period of seven years. This time was devoted to clear reasoning, linguistic studies, examination of world religions, exploration of ethics and aesthetics. It acted as a circuitous path leading back to traditional craft, now imbued with a deeper understanding of interconnection in time and place. I ceased to see craft as simply work or labor for daily bread but among the sacred outward expressions of the divine anifest

within us.

From that time going forward there have been numerous interesting experiences. Among them study of plastering traditions under true masters here in the US as well as in England, Germany, France, Italy and Morocco. Projects have included such high expressions of plasterwork as mouldings, ornament, buon fresco, stuc pierre, sgraffito and tadelakt.

I’ve been privileged to teach for the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, where I currently reside and for the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art across the US. “Sharing is caring” – such a corny cliché but so true. I hardly know a

thing that hasn’t been practically served to me on a platter. I’m grateful first of all, but now that I might actually know a few things, it becomes my responsibility to be generous as well.

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.