Carroll William Westfall

The Republic’s Architecture, Not a Partisan Style

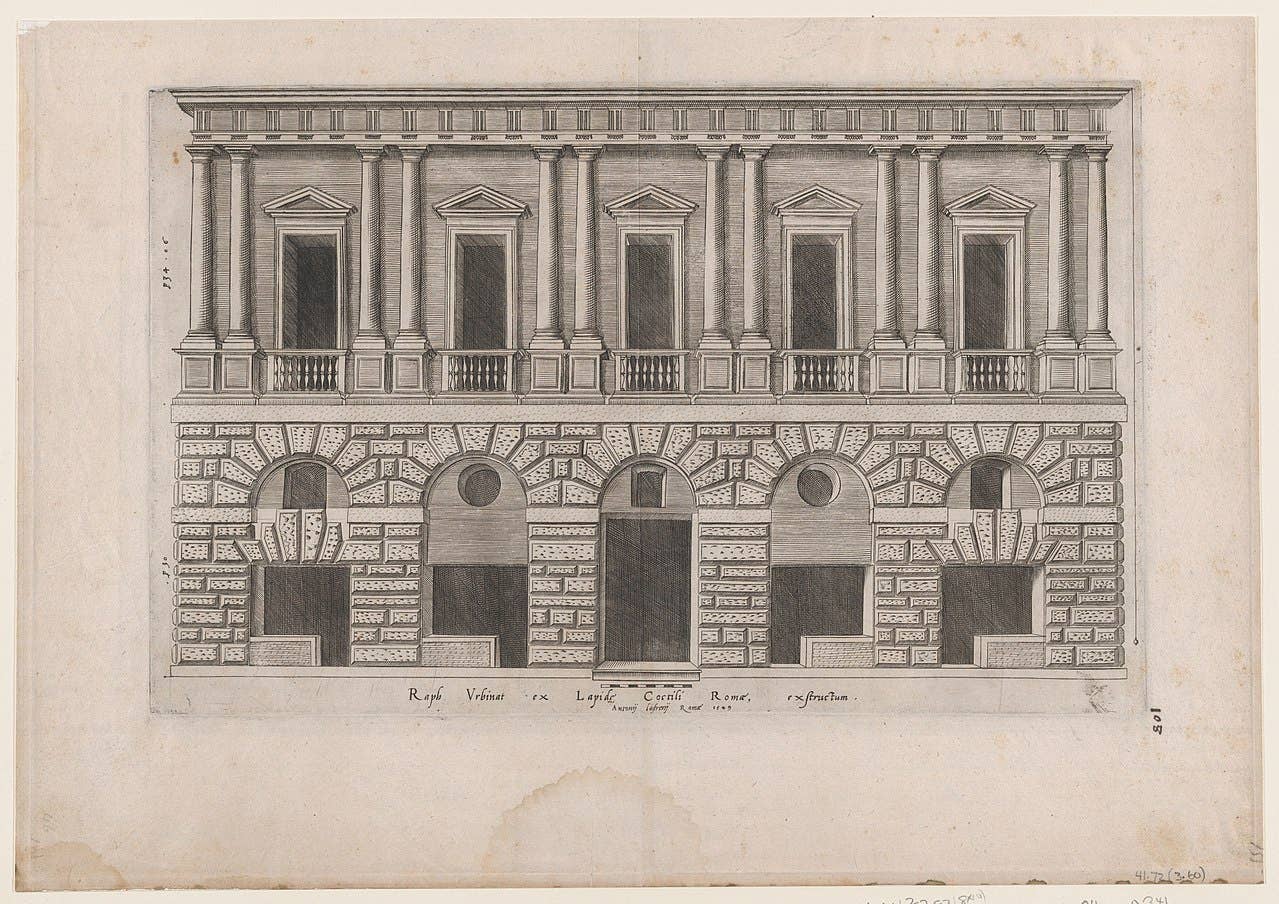

Vitruvius explained the role of “suitable public buildings” to the “divinely intelligent” Augustus who as emperor was “solicitous … of community life and the body politic.” This is the classical that the founders used, and it remains the nation’s proper national architecture.

Vitruvius explained that the art of building had to provide firmness, commodity, and delight for both public and private buildings while buildings serving public roles had to reach the higher standards achieved through the art of architecture. It provided the proportionality between their several parts and among other building, the attention to make its beauty visible, and the decorum or appropriateness appropriate for its purpose. Decorum, a central tenet of any good political and social order, unites us to the order, harmony, and proportionality of Nature and Nature’s God, as the Declaration of Independence put it.

Until well into the 20th century public buildings stood out against the private buildings that the art of building provided. They served and expressed the government’s commitment to public happiness. In the traditions stemming from ancient Greece, the forms of government and the appearance of buildings changed, but the buildings retained their of being visible, beautiful counterparts to the moral principles embodied in the common good. When our founders framed the Constitution and built the buildings to serve its institutions, they drew from for the deep well of that experience.

While the American colonies were brewing revolution, intellectuals on the Continent were challenging that understanding. They shifted beauty from being a counterpart to the good and made it a quality of an artifact that provides delight to the eye of the beholder. They also quit identifying a building based on its purpose in serving the good and gave it squarely to the style of its appearance. They then used styles as markers of the eras of civilization’s progress—from primitive to ancient, medieval, back to the classical, and now the modern era’s modernism. The wrote history as a cavalcade of styles, each one distinctive of its time, and each new one making all previous styles obsolete.

Beauty was pushed aside, and with it went architecture’s role of providing reasoned proportionality between beauty and the moral good. The Vitruvian trilogy of firmness, commodity, and delight applying to the art of building, always adequate for private buildings, was now accepted as applicable to public buildings as well. On the Continent World War I’s destruction of the states that were heirs of the ancient civil order led architects to claim that a new age had appeared and it demanded its own style. Styles uninterested in beauty and unconcerned with the common good were invented to feature new materials, new technologies, new functions, new civil orders, and creative liberty unbounded by past styles.

The exponents of this new architecture reduced the classical to a style, charging it with being an impediment to progress and the tool of nazis and other totalitarians. In this country the artistic avant garde and commercial interests embraced these new styles, and the federal government finally did so in 1974. Modernist styles became the emblems of the liberal, progressive future; by 2020 the architecture establishment was thoroughly committed to them.

Among the final actions in his first term, President Donald Trump launched a program to give preference to classical architecture for new federal building. President Joseph Biden, within weeks of assuming office, cancelled the program, but Trump, immediately upon regaining office restored it, again with the predictable outcry from architects.

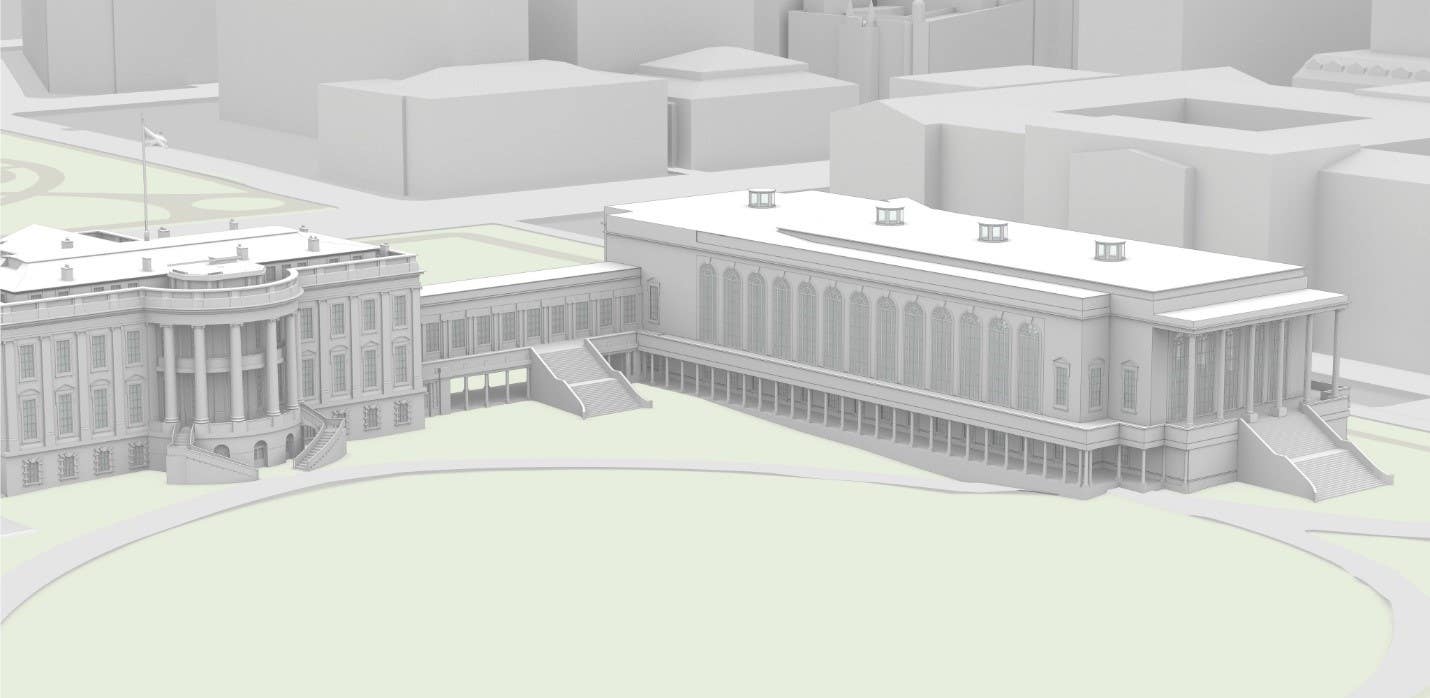

The styles of buildings had become proxies in a partisan war: modernism = liberals, progressives, and the left, while classicism = conservatives, MAGA, and the right. Trump the builder went to work at White House, adding a pair of flagpoles outside and gold gewgaws in the Oval Office and Cabinet Room. The paved over rose garden became “The Rose Garden Club at the White House” where insiders are served from the White House kitchen. For the upcoming 250th celebration he wants a triumphal arch and a Garden of American Heroes. And for state dinners and other gala affairs he has plans for a ballroom. Earlier in life he built in modernist styles; as president, he wants the grandeur of Caesar and the gilded glimmer of Louis XIV.

Eager to begin he unlawfully razed the East Wing, destroying buildings going back to Jefferson, Latrobe, Charles Follen McKim, and the final expansion in a 1942. The outcry was overwhelmingly negative, although in the Washington Post Catesby Leigh noted that the initial proposal for a 650 guest ballroom was reasonable but the enlargement to 999 was not, and certainly not the now 1350 or larger capacity noted in a recent New York Times article.

An onsite ballroom he plans would be a gilded pleasure dome in a place he thinks of as his personal domain where he can do as he wishes. Like the presidency, it is a personal possession rather than a public trust, and as the architecture he proposes to restore to federal buildings. For him and his followers, it is the style of conservative values that will thrust a thumb into the eye of his enemies, the modernists, endorsed by people professionally involved in building and the liberal university architecture schools and the journalists who excoriate new classical buildings.

The belligerents on both sides in this battle know buildings only as styles, not as architecture. They are oblivious to the fundamental differences between styles in buildings and the classical in architecture. Styles serving personal, private preferences are appropriate for private buildings; classical architecture belongs to public buildings serving the public good. Private buildings must satisfy the Vitruvian trilogy of firmness, commodity, and delight and do so with as much decorum as the owner wishes to honor. But a building serving a public purpose must be, and look to be, proportionate to its purpose while presenting beauty and honoring decorum as the counterpart to the good. In a civil society governed by laws not kings, this public role trumps private inclinations.

Building a gilded, bloviated, billionaires’ playroom on this treasured site would make it an ineradicable trophy in the partisan style war. Building it with private money to indulge the whim of a temporary resident of a public building would taint the image of public classical architecture and impede its future restoration.

But built right, it can be the first victory in the quest to make American architecture great again. Build a ballroom, but with a reduced footprint and bulk, perhaps even smaller than the proposed original size, and reject the image of Versailles but join the American classicism of Jefferson, Latrobe, McKim, Pope, and Allan Greenberg’s redo of the State Department interior. And make it a complementary building to a modified West Wing to produce the requisite proportionality and decorum on a site that the White House commands.

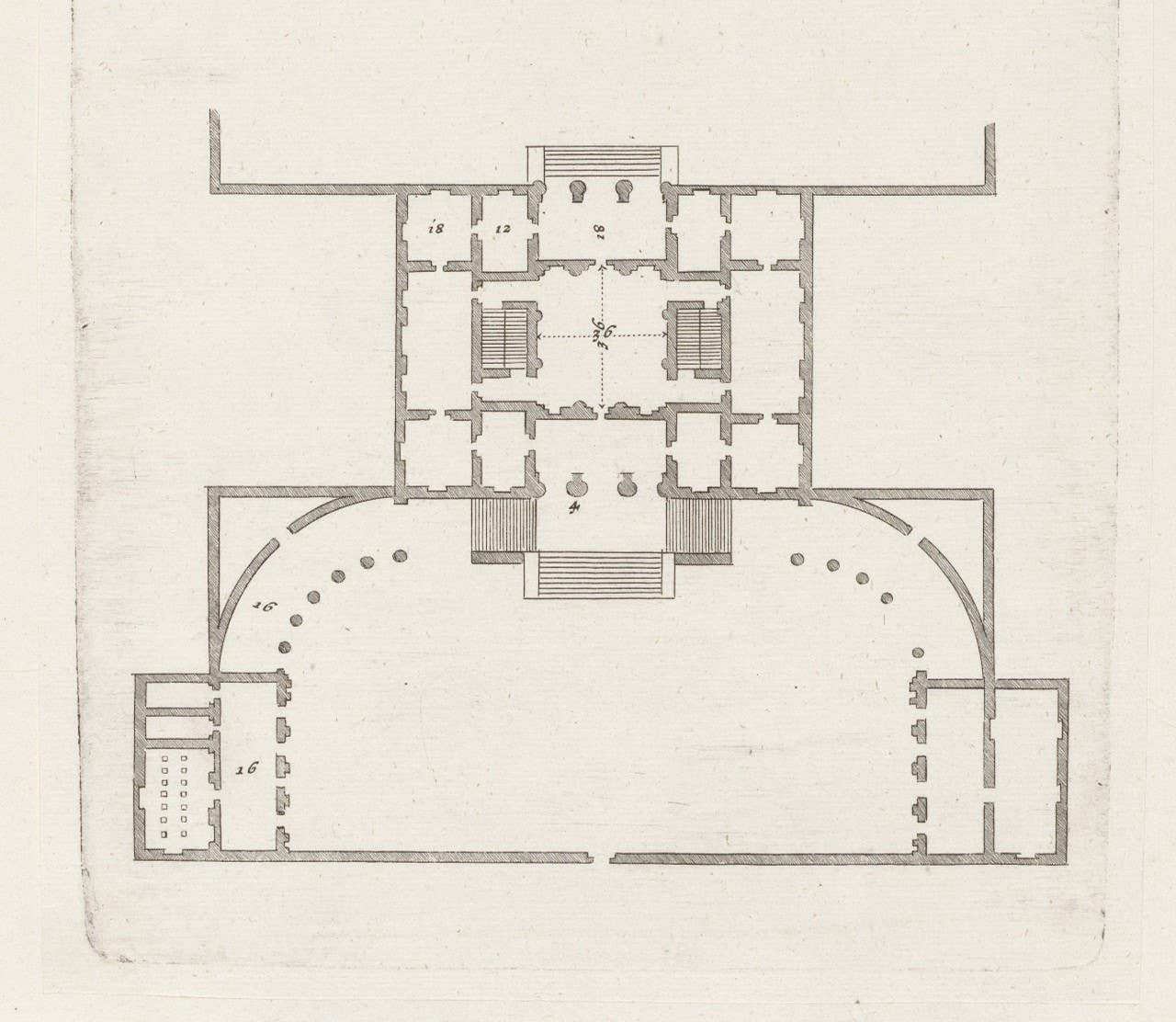

Tradition supplies ample precedents. The Palladian tradition that includes the White House has often equipped a main building with wings holding ancillary services. The White House has had them from the beginning. Larger, new wings would pull together a pair of bigger buildings, the Treasury to the east and the former War and State, now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, to the west, that were sited there for proximity to the Executive Mansion. The urbanism of the 1902 McMillan Plan that led to the Washington we know today proposed additional buildings serving executive departments for three sides of Lafayette Park facing the White House grounds; they were later built in the Federal Triangle.

Then, ban modernist styles for public buildings and instead build proper classical architecture again. With the new White House complex as a model, implement a program that recognizes that classicism is not a style easily done by favored GSA firms and on the quick. It is instead the architecture designed by skilled architects and built to serve public purposes with beauty as the counterpart to the public good they serve.

Implementing and sustaining this program would include the involvement of the public in decisions about what is built . and it would require the administration and review of knowledgeable people. We did it before, when the McMillan Commission in 1902 proposed building the Washington we have today and installed guardians to protect it. Unfortunately, modernists infiltrated the guardians, and the city began being mauled. It can be made great again.

Architecture stands for the nation that builds it. Concerning the standing of our nation we might ask the question a lady did of Benjamin Franklin at the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. “Have we got a republic or a monarchy.” “ A republic,” replied the Doctor, “ if you can keep it.”

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.