Carroll William Westfall

Against the Style Parade: Purpose as the Ground of Classicism.

Classicism and it variant words is a workhorse in architecture. In the history of architecture first published in 1943 that became the mother of all subsequent histories, Nickolaus Pevsner warns “against confusion between three terms classic, classical, and classicist.” Classic demotes “the rare balance of conflicting forces which marks the summit of any movement in art,” and classical refers to “anything belonging to or derived from Antiquity.” Classicist, like classic and classicism, belongs to ”aesthetic attitudes.”

Two factors are important here. One concerns aesthetic attitude that developed in the 1700s when works of art were prized more for the pleasure they offer the senses than for their beauty that that portrays the order, harmony, and proportionality of Nature that engages the mental facilities and are connected to the moral good. Beauty now resided in the eye of the beholder and distant from the intellect. For Pevsner, beauty was irrelevant.

The other factor was the identity given to buildings. Pevsner’s “Introduction” opens with the memorable line, “A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture.… The term architecture applies only to buildings designed with a view to aesthetic appeal.” His is “a history of expression, and primarily of spatial expression.” Forget purpose and focus on appearance, that is, on style, the evidence of the Zeitgeist or the “changing spirits of changing ages” over time.

Histories presented chronicles of changing styles. They taught architects to move with the times. In earlier ages existing buildings and treatises informed architects as they made new buildings by drawing on buildings serving the same purpose and modifying those precedents to account for changed interpretations of beauty and changed contingencies. These sources and practices connected architecture to other fields of knowledge that activated the religious and civil orders. Histories began replacing treatises in the 1800s and architects absorbed and put into practice the rules governing the historians’ narrative: one style per era; each new style makes all predecessors obsolete; recurrences are branded as revivals; and the spirit of the age (Zeitgeist) commands the march of the styles through time.

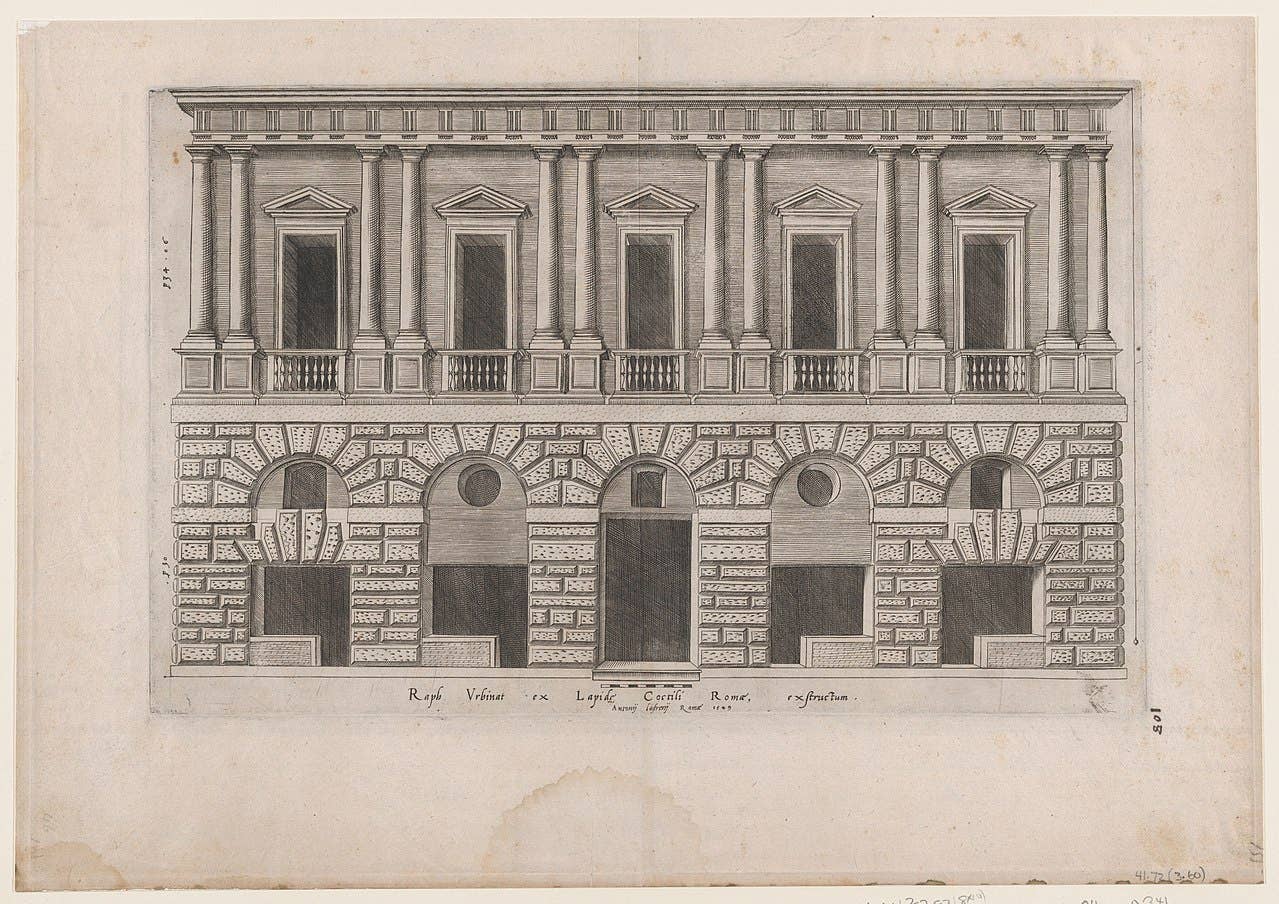

The antique spirit, that is, classical architecture, is “truly revived in the gravity of mature Bramante and Raphael,” and then it stumbles into Mannerism. Peruzzi’s Palazzo Massimo “disregards all the canons of the Ancients.” Pevsner skips over another Mannerist classic that is our concern, the Palazzo Maccarani Stati (it has several other names). It was designed by Roman born Giulio Romano who at age 21 was among Raphael students finishing his frescoes and undertook this major commission before pursuing fame and fortune in Mantua in 1524.

The Roman palace is no longer a dark brown, brooding mass whose northern front deprives it of shadows highlighting its architectural elements. The east facade catches better light, but the three narrower bays on the west facade face a very narrow street, and like the other side stops short of the interior’s depth that extends behind unarticulated stucco. The 19th century’s superelevation on the northeast corner remains. The interior now holds Senate offices.

A standard academic stylistic analysis presents its facades’ clear dependence on Bramante’s c. 1514 two story Palazzo Caprini, which Raphel bought and was subsequently destroyed and well known through Antoine du Pérac Lafréry’s atlas. A drawing of its corner is attributed to Palladio. The differences are obvious: the ground floor is higher, the shops’ arches are now flat arches with heavy voussoirs, the shopkeeper’s windows have surrounds, and the entrance portal takes command with a pediment filled with vertical voussoirs lacking a spring point. The piano nobile windows with alternating pediments are set on bibs rather than balusters, and they reside in let in panels, each in a bay framed by a low relief pilaster whose capital dissolves into the entablature’s architrave and frieze with a thin, barely projecting cornice. An added third floor largely reproduces the one below but is less tall with windows set in a let in panel and framed and topped by suppressed arches. Its pilasters lack any transition to its architrave, and its terminus in a thin cornice.

This exemplifies Mannerism. “If balance and harmony are the chief characteristics of the High Renaissance, Mannerism is it very reverse; for it is an unbalanced, discordant art.” Antiquity is the ultimate source of its classical style; and the aesthetic attitude it evokes is clearly that of classicism. It is a clear departure from the High Renaissance style seen in the Palazzo Caprini or in the Palazzo Farnese, and it shows that the Zeitgeist decreed that it was time to move on.

No architect or patron before the 1800s thought in the terms that Pevsner used. They did not think in terms of style, and they knew nothing of aesthetic intention. Their interest was in beauty and fitness for purpose. Every building had to satisfy the Vitruvian trilogy of firmness, commodity, and delight, and the important buildings then elevated construction to architecture by investing them with the proportionality that connected them to Nature’s order, with the adjustments that contingencies required for the precedents that identified the purposes, and with the decorum that assured that they fitted their purposes and places in the city. From ancient Athens forward, the buildings’ beauty was the counterpart to their service to the common good. After the Zeitgeist was given the upper hand in the 1800s, patrons and architects began making buildings that are built as technological exercises competing as styles in popularity contest.

Rather than using style in assessing a building, consider the purpose it was built to serve. A palace was the seat of a person or family wielding and exhibiting political power. Renaissance palaces strengthened that purpose by using classical architecture. In Florence it affirmed the city’s foundation by the ancient Roman republic and separated it from the control of feudal barons claiming imperial authority. In drawing on ancient precedents, in Book VI of Vitruvius’ recently recovered treatise they found specifications for the residences of important families. They were divided into two zones spread across a single story. One has the public areas open to anyone where the pater familia received the salutatio of his clients and others seeking favors with its vestibule, courtyard (cava aedium), atrium, peristyle, and ancillary rooms for doing business. The other, the personal area, has bedrooms, dining rooms, baths, etc. with “no possibility of entrance except by invitation” (VI, 5, 1; Rowland).

Renaissance architects organized those areas into a compact, multistory mass with a facade coordinated with the interior. Previously, the public business was conducted in the loggia, usually 1 by 3, in front of the private quarters in the stumps of tower house in the family compound. Cosimo de’ Medici’s palace incorporated the loggia into the ground floor giving access to the public cortile (its four arched openings were originally open) with the personal areas in the upper stories (the present grand stairs dates from the ducal period). The facade’s fictive ashlar on the upper stories acknowledges the newly gained classicism, but the heavy rusticated ground floor and window designs firmly plant the building in Florence.

A similar classicizing of traditional palace construction was also occurring in Rome. On the Campidoglio, the municipality’s building was built with halls and rooms behind square cross windows below a lower third floor and above an arcade before various offices. The modifications to the contiguous ducal palace and the Vatican’s new Wing of Nicholas V would be the model for several new palaces including the Palazzo Venezia’s first and second phases. Elsewhere I suggested that Leon Battista Alberti may have been behind this compositional type for these palaces for Roman potentates and based on local precedents: three stories high with a tower adding a story at one end, with battlements and a stucco facade articulated only by string courses at each floor, sometimes with ground floor shops, and a grand entrance leading to the cortile with the grand salone on the piano noble behind square cross windows.

The audience for these buildings was local. In 1503 Julius II expanded it to universality, and he shifted the architectural precedents from local practice to ancient imperial Rome. We see the shift in comparing the Capitoline municipal palace and the Bramante’s Palazzo Caprini for a notable local family. His enlarged Vatican Palace hid Nicholas V’s Wing and became the model for ambitious Roman families such as the Farnese.

Giulio Romano’s big palace for a family claiming importance in ancient Rome and avoiding the papal orbit elides a connection with the Vatican while clearly linking it with ancient Rome. Access to its cortile, carved out of older fabric, is emphasized by the exaggerated size of the rusticated blocks and the portal’s farming. A connection to Rome’s towered quattrocento palaces is subtly signaled by doubling the pilasters on the corners, suggesting towers and making those end bays slightly wider (the unfortunate addition of the rain water pipes botches the appearance).

This reading rather than a stylistic reading of the building teaches several lessons about how to implant Vitruvius, ancient precedents, and current developments in new buildings. Form follows precedents and purpose, not style and function; functions after all, are merely transient ways to accomplish a purpose that is enduring and deserves classical architecture. Present day classists can indeed make beautify buildings that serve the common good and stay free of the sterile style parade.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.