David Brussat

Love, Beauty and Architecture

Steve Mouzon, an architect in Miami, has been for years the strongest advocate of lovability in architecture. He correctly sees lovability is a crucial factor in the creation of a living environment, and in assuring that people care for it (and take care of it) well into the future.

Mouzon expounded his lovability theory in his book The Original Green, and has written an article on his blog called “Lovability Gains Momentum.” It cites other articles wondering why most architects treat love as if it had the cooties. He notes that professionals in other fields do not feel the same angst that architects do when it comes to embracing the idea of love in their work. Most architects have a similarly strange reaction to the idea of beauty.

By the way, I am with him 100 percent on the importance of lovability in architecture. In the following passage, from the article, he describes a conversation with his wife Wanda during their third year of architecture school, and then he makes a key point:

“Why [asks Wanda] do you refuse to design buildings that anyone else I love would love?”

“Do I?”

“Of course you do!”

“How do you know they wouldn’t love what I design?”

“Have you ever listened to non-architects talk about architecture?”

“No, our professors tell us that we should educate the clients.”

“Well, if you’d ever stop and listen to them, you might learn what they actually love.”

The point to this story of the origin of my use of the term “lovable” is that the term requires something many architects are completely incapable of demonstrating: humility. Listening to the untrained requires humility.

Precisely. Architects are trained to rise above humility – a big mistake in their education. The idea that the public needs to be educated to appreciate their work arises from most architects' profound ignorance of human nature. Their instincts are suffocated in architecture school. In fact, they are the real untrained. Humans of every station in life have spent their entire lives interacting with architecture at a degree of intimacy far beyond that given to any other aspect of their aesthetic life. Only architects seek to purge that intelligence from their minds.

People do not read poetry or watch plays or see sculpture every day of their lives but they experience architecture almost every moment of their lives. They may not think much about it – indeed, in today’s built environment, numbness to one’s surroundings is a sort of required defense mechanism – but their brains do. So people develop a judiciousness regarding architecture far more sophisticated than that which architects develop in architecture school – which is mainly a process of unlearning all that life has taught them about their built environment in their lives up until matriculation.

Of course, most people do not know how to build a house, but shown two houses they can reliably choose the one that most appeals to them – and their choice arises from decades of experience. Their sense of taste is well developed. They will almost always choose a more traditional over a less traditional house – and that is an expression of intelligence that a refugee from architecture school can almost never equal. This is why almost all architects are in denial. They are, in key respects relating to their own profession, stupider than almost all of those they themselves consider stupid.

So stick you head in the sand, architect! That’s where it is and that’s where it belongs until you wake up from your egotistical dream-world of self-love.

I’m sure Steve and Wanda have shucked most of what they learned in architecture school, which is why what they say about lovability in architecture deserves respect. Let’s hope lovability is indeed gaining momentum.

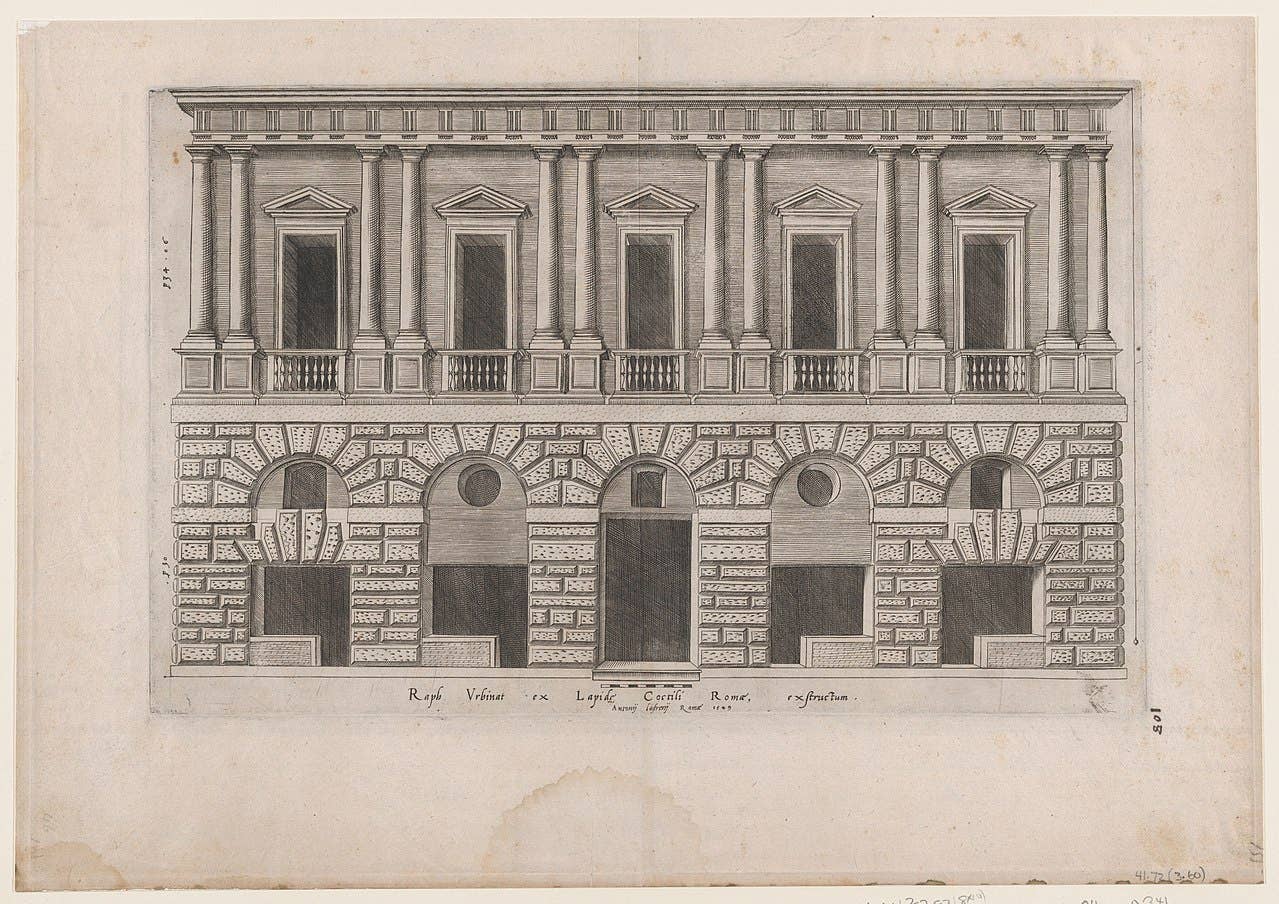

On another note, Steve hopes to publish soon the second edition of his Living Tradition: Architecture of the Bahamas, which today is out of print. The blog RJohnTheBad, in a post called "Steve Mouzon makes me crazy sometimes," writes that Mouzon incorporates into his analyses of building the phrase "We Do This Because," explanation of which clarifies many otherwise tangled architectural issues. Bad John says that the book shows readers step-by-step how to pick "a consistent level of grammar for your building, deciding how plain or how fancy you want to build and [how to stay] within that zone."

Steve has just concluded a Kickstarter funding effort for the second edition, but has begun a list of people whose donations came in too late for the campaign, which he is continuing on his own. Readers can email him at steve@mouzon.com.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.