Carroll William Westfall

How to Make Use of History

In my previous blog I presented the deficiencies of our current, canonic architectural history, calling attention to its stress on style and invention and its lack of attention to architecture traditional role of seeking beauty and serving the common good. Modernism’s commitment is to internationalism, but architecture is necessarily a national pursuit. Modernism is a progressive movement that uses revolution to annul tradition. It has little interest in serving progress by making innovations within tradition.

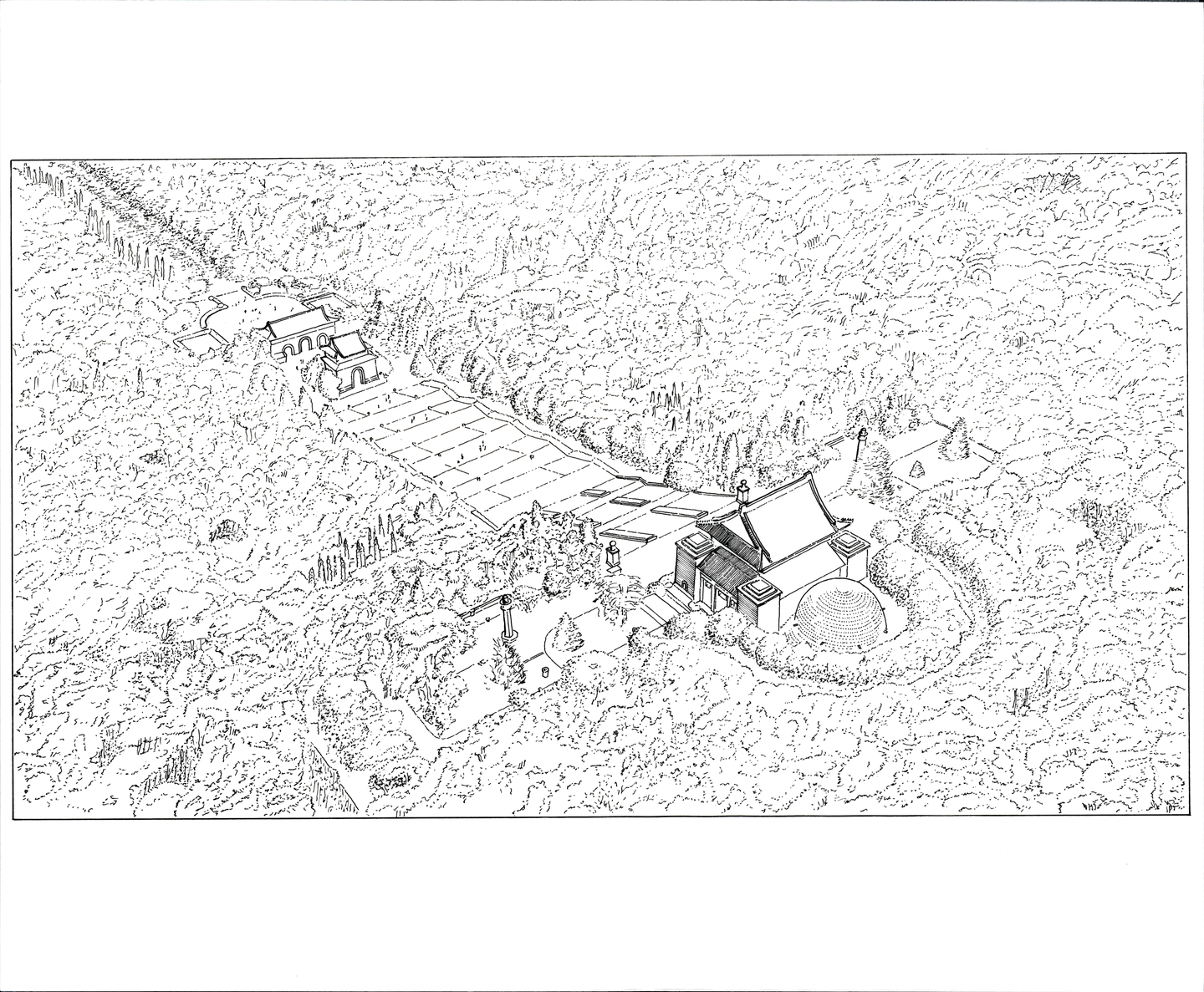

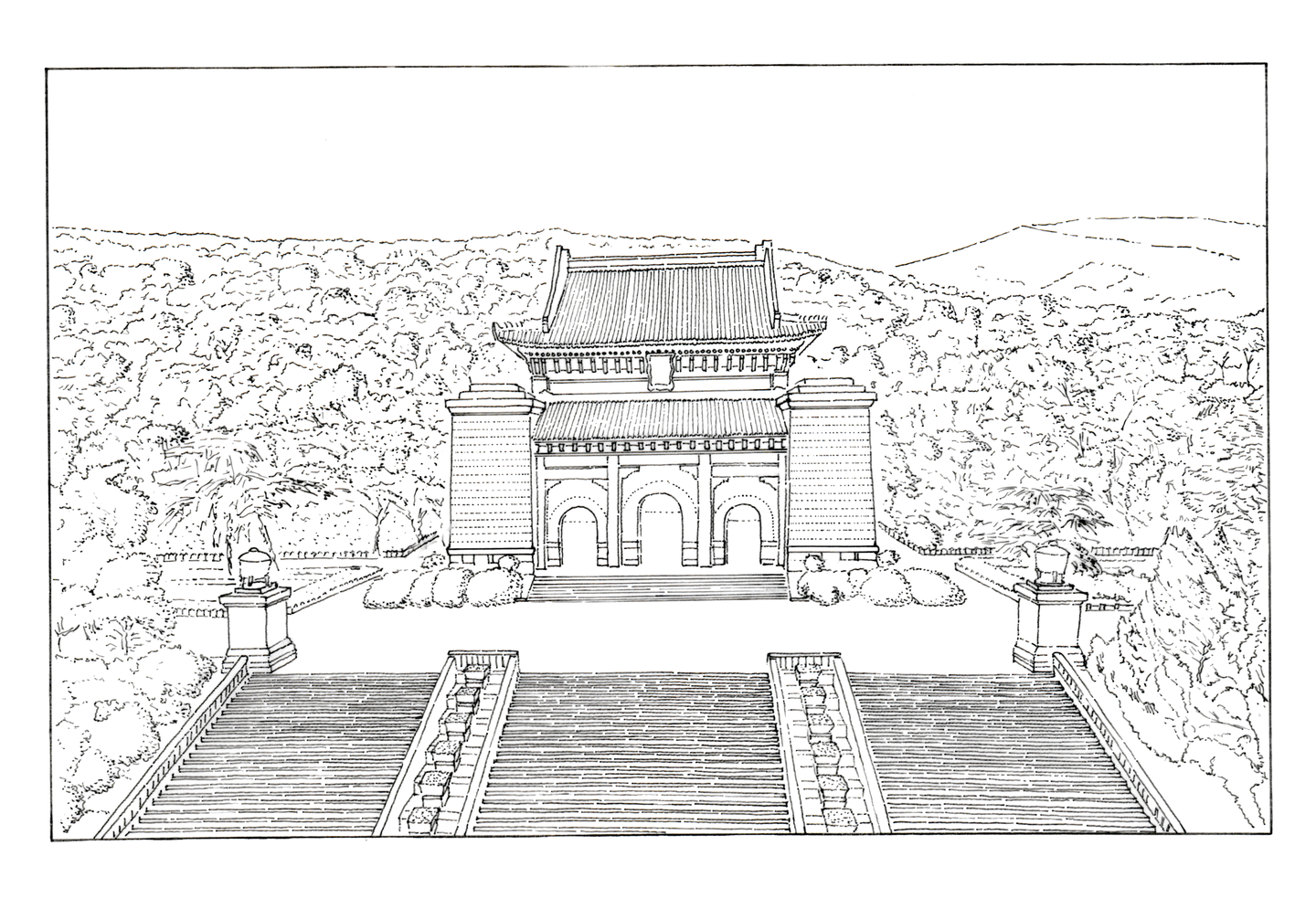

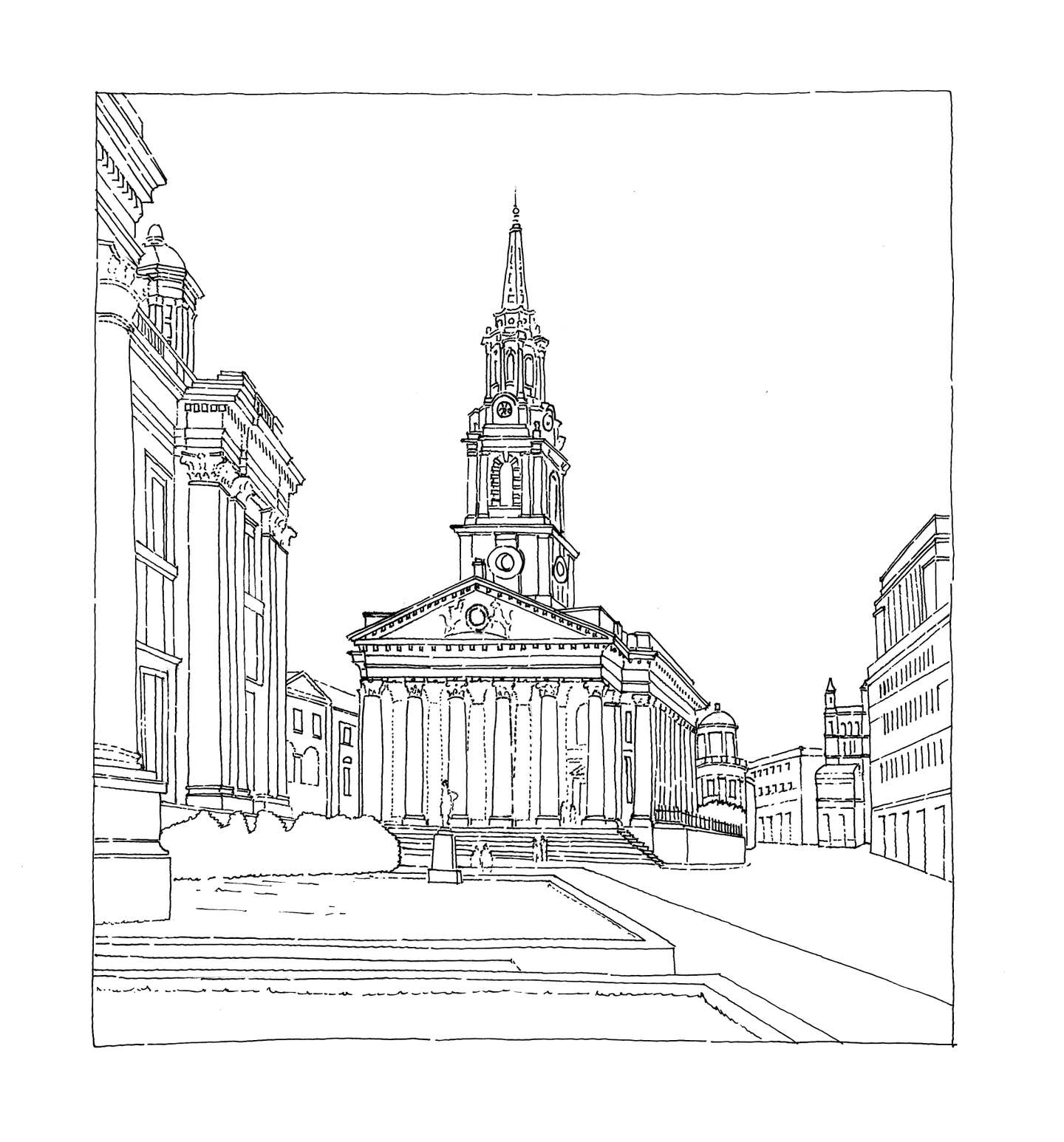

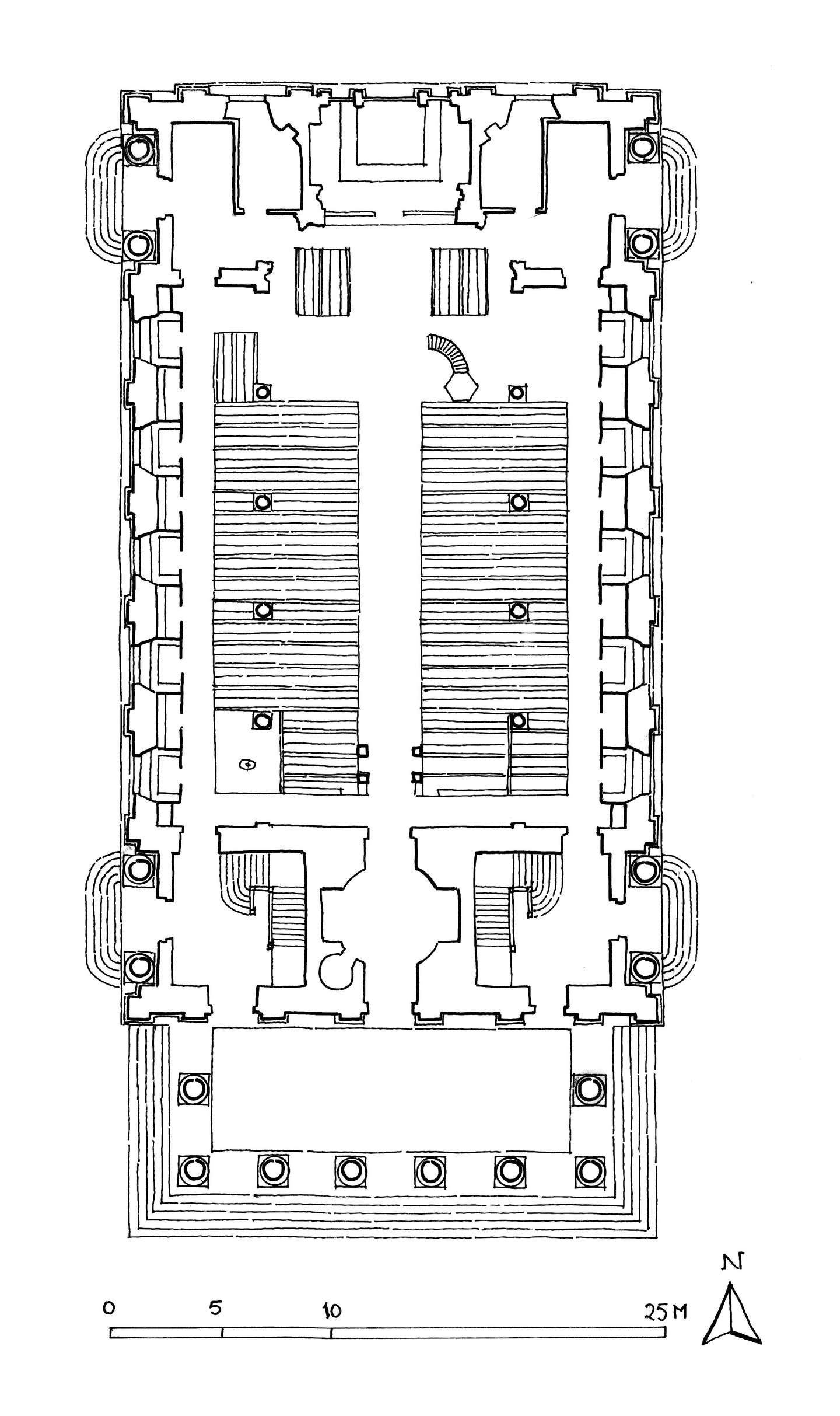

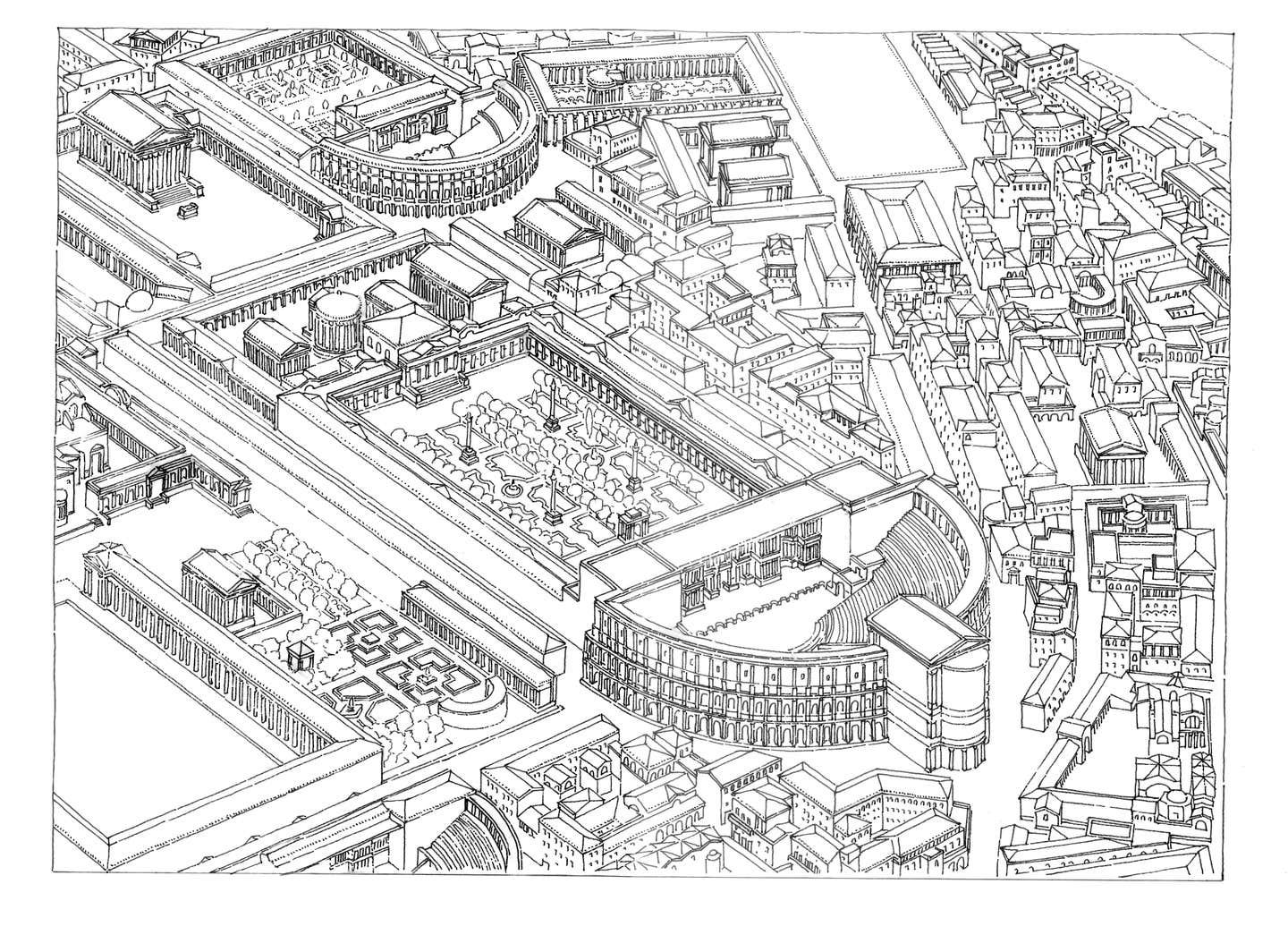

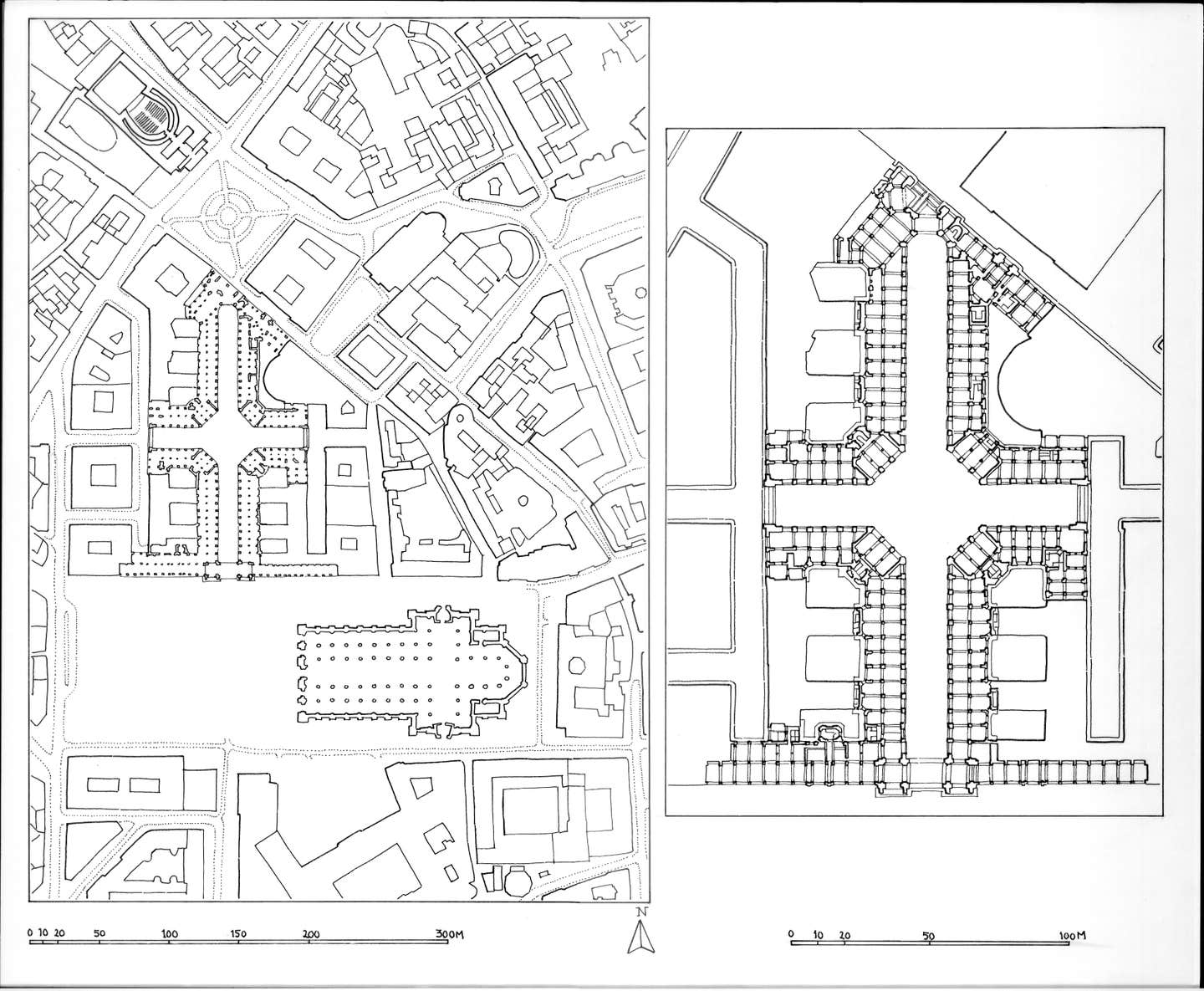

To provide a basis for reinterpreting architectural history so that tradition can play its proper role in practice, my Notre Dame colleague, Samir Younés, and I collaborated on a book published this year titled Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture (New York: Routledge, 2022). It is a preface, a prolegomenon, or a guide for interpreting architecture, but it includes no narrative marching through time. It assumes the reader is well equipped with photographs and, better, with personal knowledge of a broad range of traditional buildings and hopes to extend the tradition with new buildings that fulfill architecture’s twin roles of serving the authoritative institutions that serve the common good and doing so with beautiful buildings and urbanism. Authority, here, designates the common set of agreements that we call civic laws. Such agreements gain authority because they demonstrably guarantee our collectives as well as our individual freedoms. Professor Younés’ drawings of more than 100 buildings illustrate the text, each with our commentary, sorted according to the purpose they serve and usually in chronological order.

We stress the inescapable fact that a building occupies land that is under the authority of a government. This necessarily makes it a public object, and, whether built by a public authority or a private interest licensed by that authority, its purpose is to assist government in promoting the common good.

For the role of style we substitute several alternatives. One notes that the necessary support for any work of architecture is the integration of the three legs of a tripod, the tectonic or material means, the expressive character that displays its role in serving the common good, and the urban that gives a building its proper place in the civil order’s urbanism. We explain that these legs are operative in traditional architecture no matter the tradition.

We also identify a building’s massing of components or its spatial configuration, its identify its membrature made out of other buildings or their parts, and discuss how together, configuration, composition, and membrature produces its expressive character. We emphasize the constant change in national architectures as they remain vivid and useful through receiving innovations that reform traditions to serve changed circumstances.

And finally, we stress the distinction between purposes and functions, with purposes serving enduring civil or religious ends and functions providing changing means for doing so.

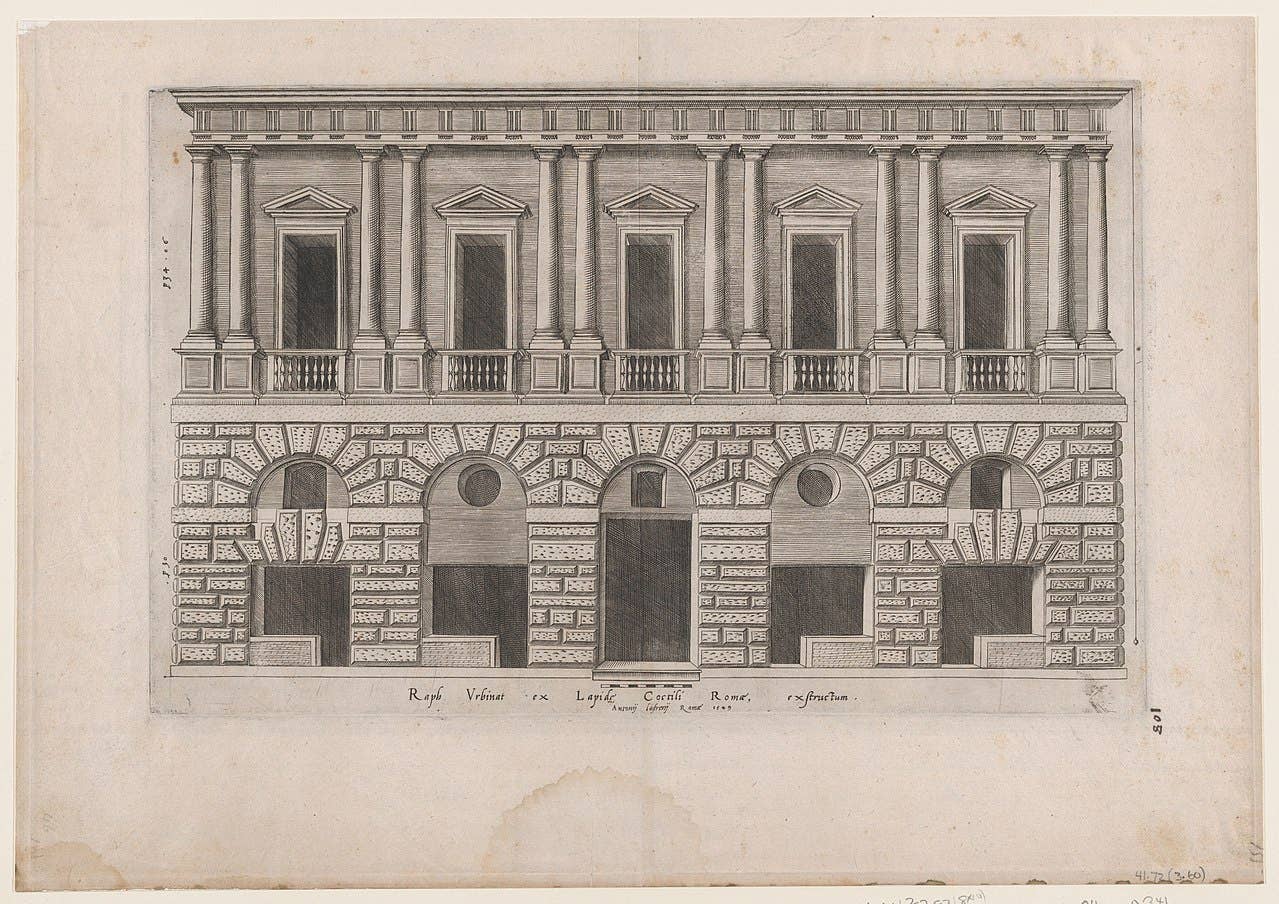

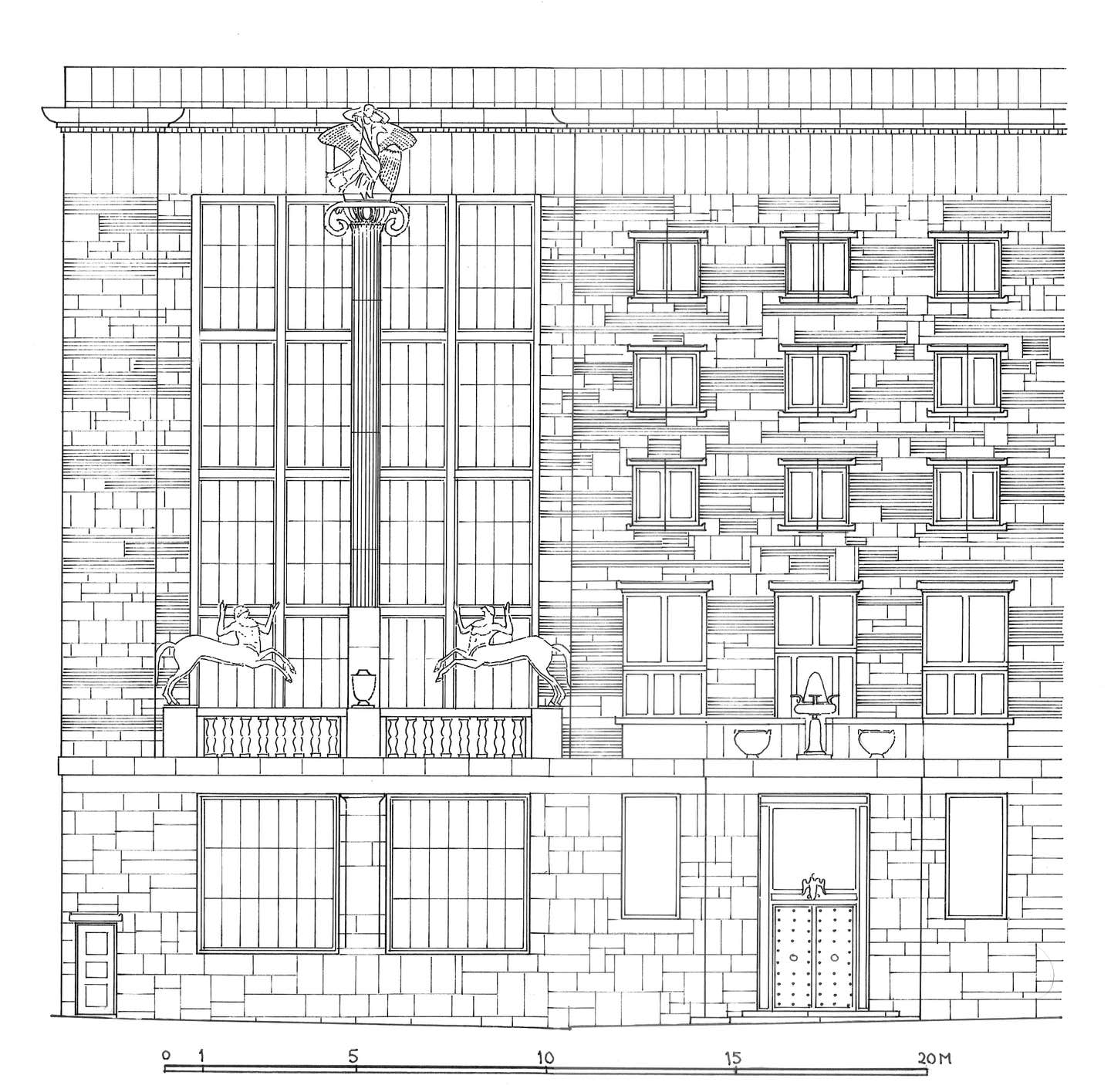

Our discussion of the tectonic leg explains that the architect marshals three kinds of material components, pieces, elements, and motifs. Pieces are the smallest components in an assembly. In the classical orders they are the base, shaft, capital, and entablature or arch with its voussoirs that are composed to make an element, or one complete structural unit. In a masonry wall the pieces use are bricks and stones arranged as sill, rise, and coping. Another is a bay composed of the three orders or piers or walls supporting an entablature or arch. Another is an opening’s embrasure. These and others like them are composed to produce a motif. Examples are a wall articulated by bays, a colonnade, a Palladiana, a temple front, a dome. These motifs are assembled into compositions that produce the material membrature that encloses the configuration and, with ornament and decoration, complete the building’s expressive character.

In the classical tradition these material components remain visible and identifiable, even fictively as when a rubble wall or brick column is stuccoed or steel columns and beams are enclosed by terra cotta. A good design satisfies both sets of Vitruvius’ criteria, those of the art of building (commodity, firmness, and delight) and those of architecture (symmetria or proportionality, eurythmia, that is, the adjustments needed for beauty in the assemblage, and decorum, or the expressive character appropriate for its role in the civil order).

The expressive leg uses the arts of building and of architecture to make visible building’s role in serving the common good by synthesizing type and character. By type we do not mean any of its casual uses in speech and narratives today, such as functional types (e.g., church; factory; residence), compositional types (e.g., skyscraper; center-hall residence), or styles (e.g., early Renaissance classicism or the multitude of style types within International Style Modernism). Those belong to a Modernist way of thinking and reveal little about traditional architecture

Instead, we use the word type as shorthand for idea-type or generative-type that identifies the role a building plays in the common good. We identify seven types that are not bound by national customs and habits. Instead, each type has a distinctive generative image serving one of the seven purposive activities devoted to serve the common good universally in different times and climes. (See accompanying diagram.) Some buildings serve more than one purpose; they hybridize the types.

The tholos (1) serves the veneration of what is worthy of worship.

The temple (2) is where people assemble for celebratory rituals and ceremonies. Churches are commonly hybrids with a tholos farthest from the entrance.

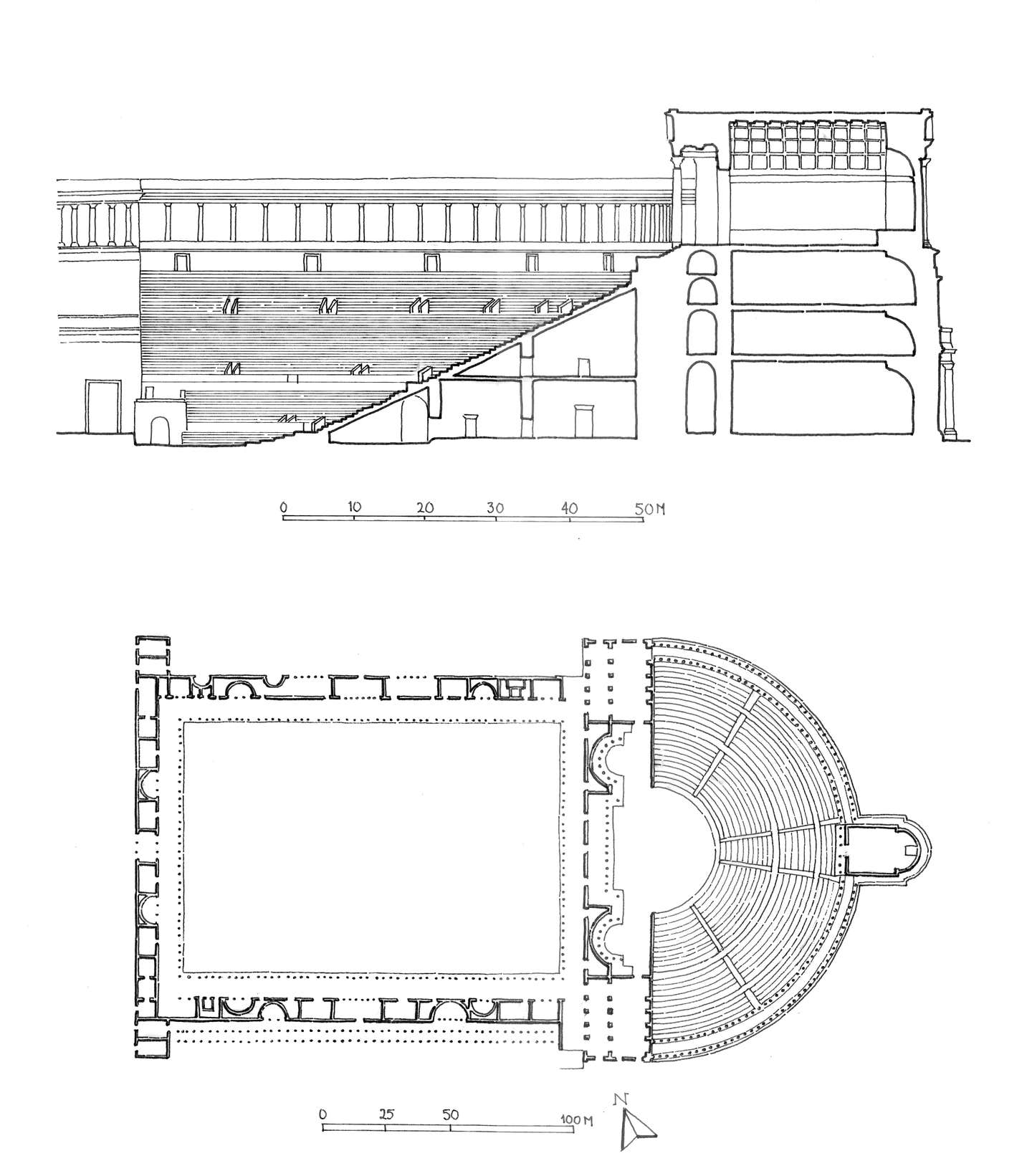

The theater (3) serves engagement of participants with dramas or councils for imaging improvements in the fates of the assembled or of the world.

The regia (4) protects authoritative public institutions and individuals.

Those four are ranked highest while others fill out the civil activities and urbanism. The dwelling (5) shelters those lacking authoritative roles and is often combined with 6, the shops, that serves trade and manufacturing.

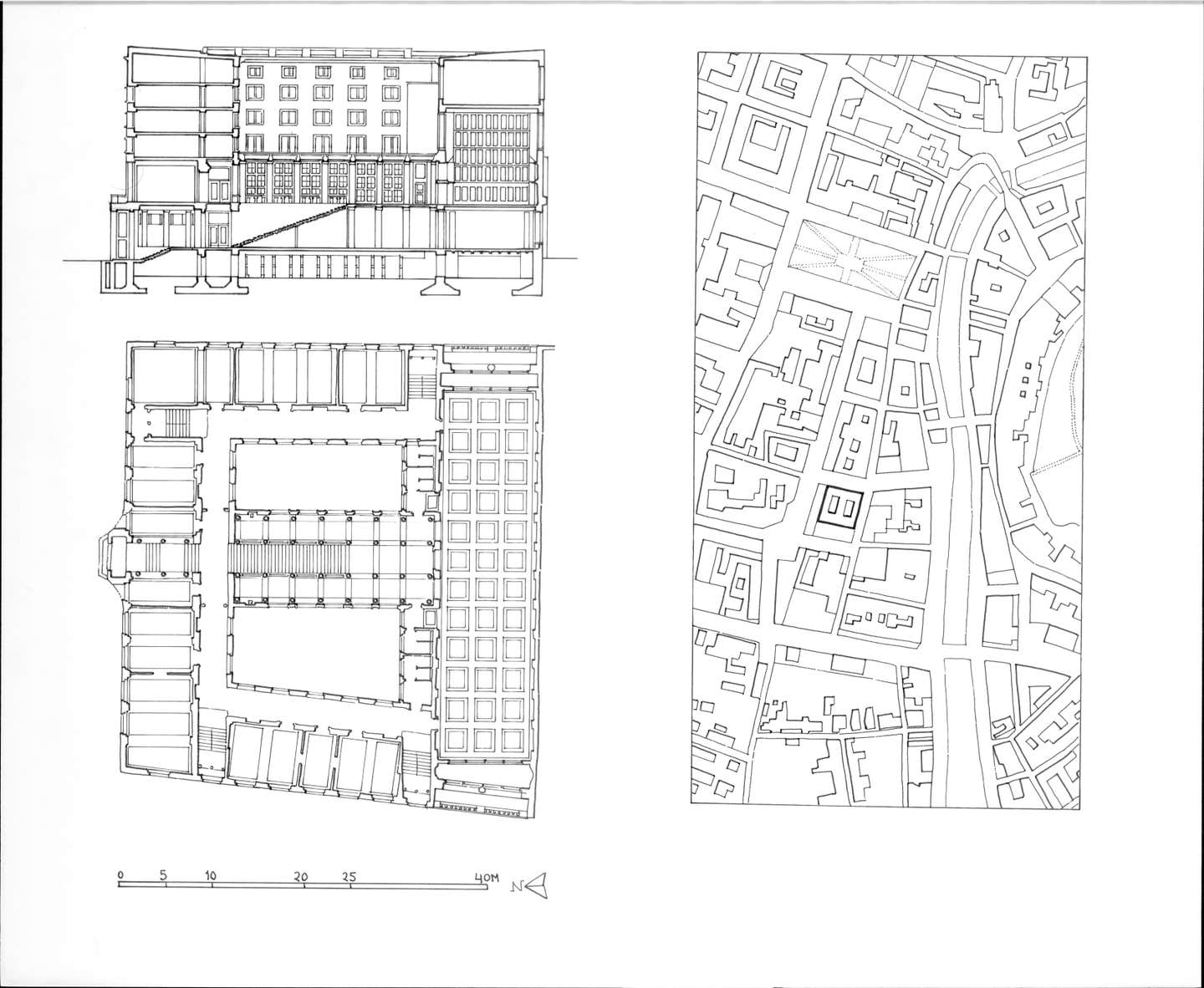

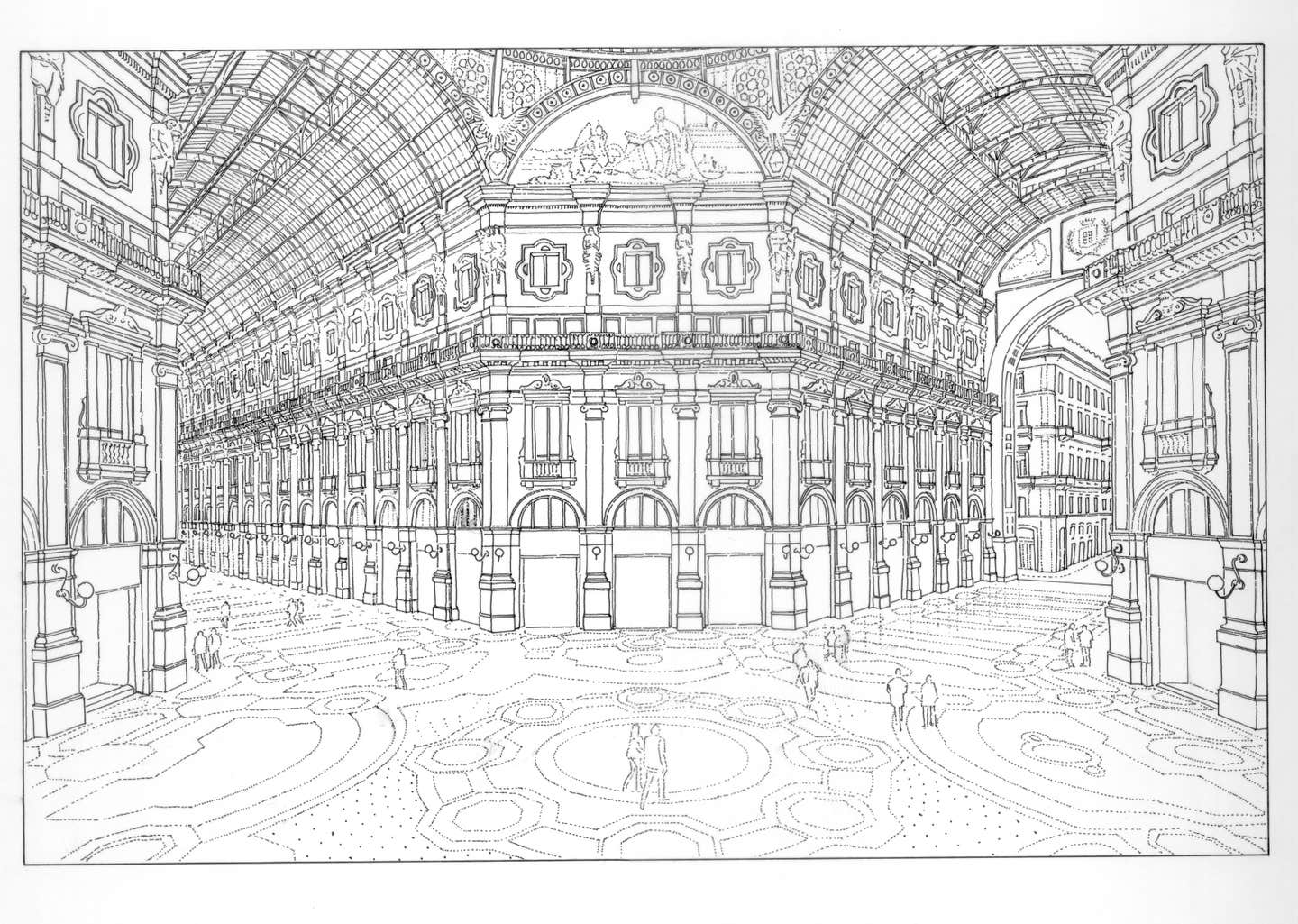

And finally the hypostyle (7) that serves gatherings for various roles, functions, purposes and other activities. When enclosed, it may be spanned with trusses; when stacked, it makes a highrise. It is often ornamented and decorated to identify its function(s) and even purpose(s).

A building is generated from the idea-diagram appropriate for the purpose(s) the building is to serve. From it is made the parti that controls the plan’s development of the configuration that is enclosed externally and supported internally by the membrature. A traditional building rarely makes its type-diagram difficult to discern.

The membrature composed of the tectonic leg with whatever ornament and decoration it carries is the public face that identifies a building’s role in the common good by calling to mind the buildings that have traditionally served that role or can easily be seen to do so. These buildings include extant predecessors and allies, including those that have been modified over time with innovations responsive to present conditions. The range of predecessors is to be at a scale commensurate to the reach of the authority it exercises, whether national for top-tier government buildings or site-specific for dwellings, or somewhere in between. Here we see that in a very real sense, a building is excavated from its site.

In addition to serving the purposes of those who build and use it is the equally important role of making the beautiful present. The beautiful is to architecture what good work is to government, evidence of the quest for the highest ideal in its role in our lives. But note: the beautiful is a counterpart and not an expression of the good. The art of governing seeks the good within changing civil orders with the nation being the most extensive. Governing exercises authority over the actions that serve the common good. Government does not command the art of architecture. That art is practiced within national traditions of the art of building, and the beautiful belongs to the art of architecture and can be achieved independently of the national traditions of governing. Beauty is agnostic. The beauty of buildings serving religion is available to believers of other faiths and to those with no faith. A western visitor to Beijing can see the beauty in the Hall of Supreme Harmony.

There is a role for the word style in this scheme, but it is a very small one. Style refers to the marks that identify when, where, and perhaps by whom a building was built, and nothing more.

The first histories of architecture were written in the 19th century. Nikolaus Pevsner’s Outline of European Architecture, appearing in 1943, became the urtext for all that followed. In all narratives the tholos, temple, theater, and regia dominate, with others entering in more recent years. Those four are to the history of architecture what the three fundamental activities of any civil order are: making laws, executing them, judging compliance with them. These three parts of governing were shuffled around, altered, reformulated, and passed on from their earliest articulation in ancient Athens and in Sinai, and they remain present in every civil order today. In recent centuries they have acquired a number of ancillary departments of government and innumerable extra governmental entities, from brotherhoods to corporations, from guilds to labor unions, whose activities have richly complicated the historical narrative and acquired buildings for doing their work.

In the civil order, many of those complications derived from the several periods of turbulent revolutions and peace in industry, commerce, technology, and the political lives of nations. Architecture’s service to them brought its historical narrative a greatly increased range buildings that have received architecture’s attention, but the types prevail. A vast array of institutions claim the status the regia, which is also the place for participants in a representative democracy with the theater for their deliberations. Commerce has exploited the flexibility of hypostyles, often decking them out as regias. The shop bas metastasized into the hypostyle. And people who find regias beyond their reach settle for dwellings stacked as hypostyles.

In the present as in the past, the tholos, temple, theater, and regia serve the most important and authoritative activities of civil orders, and not only in the classical tradition, with variations that provide their expressive character. But Modernism has proven itself unable to do the same. A restoration of traditional architecture can surely assist in restoring the civility that is needed to protect and enrich the common good that serves the good of all of us. In an age when the Modernists declare: “Look only forward and win fame!” we respond, “Draw on tradition to serve and benefit from the common good.”

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.