Carroll William Westfall

Architectural History, the Common Good, and the Beautiful

“The Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) promotes the study, interpretation and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all. SAH serves a network of local, national and international institutions and individuals who, by vocation or avocation, focus on the teaching, practice and history of architecture, design, landscapes and urbanism.”

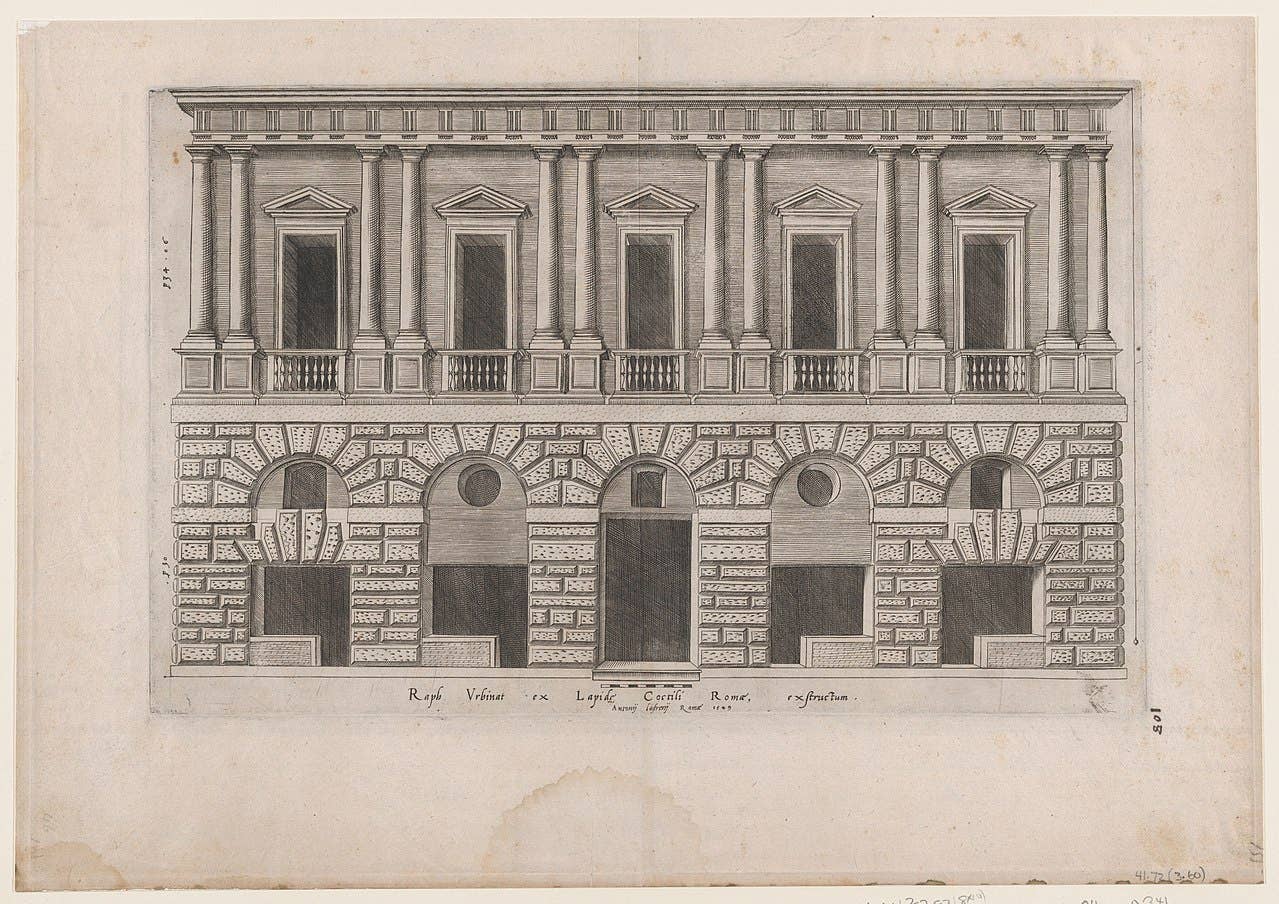

Since its foundation in 1940 historians have separated their academic discipline from the practice of architecture. Their inherited narrative puts buildings in a chronological sequence of styles, each of its time, each expressing the culture whose influences produce them. A building is an art whose style allies it with other visual arts. A style is not to be repeated in a later age. Ancient classicism was a style, and Renaissance classicism was given a pass because the whole of Renaissance culture was based on ancient culture and, as Jacob Burckhardt had declared in 1860, Renaissance man was the first of modern man who eventually invented Modernist styles.

Everyone involved in architecture has learned that doctrine: students, architects, developers, bankers, city officials, building committees, university officials, journalists, critics, and the general public. Academic historians explore details, and they teach surveys and write books that with very few exceptions teach that traditional and classical architecture are styles of earlier periods.

Their role in the 20th century is given short shrift, and inventive architects such as Bernard Maybeck, Edwin Lutyens, and Jože Plečnik are ignored. The narrative treats the past as past with nothing to contribute to the present, and it accepts architecture’s beauty as an attribute of a distinct period, offering nothing for present use except tired and vague formulae about proportions and other formal esoterica.

The narrative’s heroes are the innovative individuals selected by the Zeitgeist to channel the influences of their time into the style of their time. This teaches architects to say, “I was influenced by ….” More recently, the influences have shifted to architects who have claimed the mantle of invention to achieve fame and fortune by creating highly individualized new Modernist styles that lesser beings emulate to be “of our time.”

This effort to be modern and thereby superior to antiquity began in the 17th century. Strengthening the moderns’ claims were discoveries of natural laws that caused ancient laws of natural phenomena to be discarded. People soon began imagining similarly innovative prospects for progress in political, social, and cultural affairs.

In the waning years of the 18th century political revolutions produced tumultuous changes within nations and wars between nations, culminating in World War I. To assure peace, in 1920 the League of Nations was founded. It failed, and after World War II the United Nations superseded it in 1945.

These international institutions needed buildings, and in the spirit of cooperation the League held a competition to find a design, but the nine European jurors could not find agreement, so in 1928 five others designed its headquarters opened in 1936. A similar scenario ensued at the UN.

Wallace Harrison supervised an international committee of architects nominated by ten nations. Again deadlock, until a design jointly produced by Oscar Niemeyer and Le Corbusier began construction in 1948. Its conspicuous, precocious, strictly Modernist building opened in 1950.

In traditional architecture, peer institutions build equally to their rank, and lesser institutions use appropriately diluted versions.

In 1929 it was decided to build a Supreme Court Building; its high classicism completes the triad of the nation’s top institutions. The WPA’s buildings that followed during the 1930s used the anodyne stripped classicism of the League of Nations Building already being used in the late 1920s.

After World War II the new UN Building Building’s Modernism presented the face of the future. Originating as a vehicle for anti-national and anti- traditional internationalist political reforms, Modernists shifted to making it an apolitical style for the new Modern age. Introduced in 1932 at the Museum of Modern Art, it quickly took command in an internationalism committed to Schiller’s and Beethoven’s declaration, “Aller Menschen werden Brüder.” Aggressive corporations used the new style, and soon so did like-minded, self-interested entities and government agencies in a swirling potpourri of artistic styles.

More than a half century ago Leo Strauss noted that nations do not go to war over artistic styles. They battle to preserve what they believe is theirs by right and what is embedded in their national common good. Artistic styles have no dog in that fight. (We might add, it is understandable why there is little popular enthusiasm for preserving and protecting what international Modernism builds.)

Here we meet a basic principle of architecture: Buildings are public objects on land that has been granted for them by a civil order in return for their prospective service to the nation’s common good. A building’s most fundamental duty is to serve and express the government’s authority and the role it plays in serving the common good. From Athens and Jerusalem and other ancient authorities we know that nations seek what they understand is the common good of their members. Different nations, like different individuals and different entities between nation and individual, have different histories, and these carry customs and habits that compose a world view that characterizes the nation and forms the ideals that bind individuals into a nation. Unlike older nations, ours is composed of immigrants who willingly or in bondage left their native lands and adjusted to and contributed to this nation’s world view. In the early 1960s Meyer Shapiro observed that it is easier for people to change their view of the world than to change the way they use their eating utensils. American Chinese restaurants still offer chopsticks.

Although new, our nation is a successor of ancient Greece and Rome and the heir of common law. Our liberal, democratic political order has replaced monarchy, oligarchic, and other forms of organizing political power. This progress has been achieved through innovations that have reformed valued customs and traditions. One example: we have also replaced gladiatorial contests with ritualized combat in boxing contests. This progress serves our common good, a transcendental good like the true and the beautiful. These universals are materialized in different habits and customs within world views in different times and places. Each is as valid today as it has always been. In our world view the good becomes the ideals of peace, justice, abundance, and liberty, and other people throughout the world are eager to emulate them in their nations. Its ultimate source, as our Declaration of Independence acknowledges, is in the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God,” that is, in the natural law that endows individuals with certain inalienable rights and the source of the good, the true and the beautiful.

These transcendentals are materialized in different ways in different times and climes, and in arts that are particular to it. The good’s primacy vehicle is governing and willful individual acting, and the beautiful in building, singing, and other kinds of making. These transcendentals’ content can never be fully present, but it is part of our human nature to seek their greatest possible completeness: here is the pursuit of happiness. Incompleteness always produces differences, and this leads some to think of them as only relative values. No. They are absolute, enduring, and universal, always present even in incompleteness. Expertise in the respective arts will manifest their presence, but what they offer is available for each of us without being limited by an attachment to other transcendentals. The palace of a tyrant can be beautiful, and a beautiful building can serve despicable acts: With beautiful song, Puccini’s tormented Tosca leaps to her death at the Palazzo Farnese. We can hear the beauty in a song in a language we do not know and see it in a building in a foreign land and distant time. A Lutheran can see the beauty in Saint Peter’s Basilica. And a bankrupt need not be blind to the beauty of a bank’s building.

Architecture can make beauty available through the art of building, but this role for architecture is absent from the historical narrative. Instead, we have a narrative that encourages, indeed, teaches as inevitable, the current hyper individualism in the potlatch of Modernist styles. The narrative also spuriously attaches styles to cultures and cultures to particular forms of political organization. But styles are variations within the classical tradition, and they exhibit differences in political and religious beliefs by using differences in how they render beauty. Beauty itself does not take sides; it is the common property of good buildings and absent in bad ones. The differences between Baroque Catholic churches and austere Protestants ones are variations, and so are the preference of English architects for Palladio and the French choice of the Rococo.

This misunderstanding linking styles with particular forms of political organization, which is endemic to the present narrative, blocks what is central to architecture, which is its obligation to express the authority of the government that builds it and uses it. The art of governing requires using authority to fulfill the ideals of the good, and its buildings serve the government’s purposes in doing so. Within governments, partisan positions present alternative means of doing so, and the political bodies of governments assess under the light of the true and thee good to find the best way forward. It is common today to hear architecture presented as a participant in partisanship rather than as an element in a civil political dialogue seeking the good: the left spurns the classical and the right wants a revivalist classicism. But these are partisan positions within the same political order. Might we say that the cacophony we see in Modernism’s styles is the equivalent of, and encouragement for, the partisan shouting and braying that impedes the duty to protect and promote the common good?

Rational discourse among people of good who can put aside partisan position and even their personal interest is needed to serve the common good. Might traditional and classical architecture provide an instructive model? Consider the analogy to a beautiful building: Guided by tradition with innovations to address current and particular circumstances, it assembles many parts with each serving its purpose within a whole that can take its appointed place within the urban order and serve its purpose within the common good, and to do so with beauty.

In earlier periods, histories of architecture assisted architects in building such buildings, and their builders expected as much.

But only rarely, and thankfully still, today. Restoring and broadcasting a narrative that tells such a history to students, the general public, and everyone in between would offer a tremendous benefit to our lives.

Until we have such a narrative, every architect needs to develop one for use when designing. To that end, my colleague and I have published a book that outlines how to construct that narrative.

In my next opinion piece I will provide a sketch of its framework.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.