Features

Traditional Approach, Interview with Gary Brewer

the Darden School of Business

at the University of Virginia.

Foursquare house. Photo by Francis Dzikowski/Otto

Gary Brewer is an important figure in the world of modern traditional design. Before launching his independent practice in 2024, Gary was a longtime partner and studio leader at Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA), directing a team of 25 within the 200-person office and operating with relative independence and the blessings of the founder. His work has been influential in demonstrating the value of traditional approaches to architecture across a broad range of contemporary building types. He has also done much to bring together a community of like-minded practitioners and decision-makers to discuss and debate topics ranging from the design of houses to historic preservation to traditional town planning.

Here Gary speaks with Peter Morris Dixon, who worked with him for more than two decades at RAMSA as director of external communications.

Hamptons dunes. Photo by Peter Aaron/Otto

the Cougar

Point Golf Clubhouse, Kiawah Island, South Carolina. Photos by Peter Aaron/Otto

Business School.

East Quogue, New York. Photo by Peter Aaron/Otto

in Virginia Beach. Photo by Eric Piasecki

the living room on the piano nobile of the classical

beachfront house in Seaside, Florida. Photos by Peter

Aaron/Otto

the living room on the piano nobile of the classical

beachfront house in Seaside, Florida. Photos by Peter

Aaron/Otto

Gary, it’s great to be having this conversation with you. I’ve known you for 25 years, and during our time working together at RAMSA I always considered you an essential member of the firm’s design leadership. What first brought you to your focus on traditional design?

Unlike many of my colleagues here in New York, I was raised in the Midwest. I studied architecture at the University of Minnesota under Ralph Rapson, a Cranbrook-trained modernist. After completing my education, I came east, first to Baltimore, where I worked for RTKL, mostly designing festival urban marketplaces. I came to New York in 1987 to work with Sam White, at that time a partner at Buttrick, White & Burtis, who taught me a lot about architecture and New York culture. Then in 1989 I joined Bob Stern’s office. The 1980s were a heady time in architecture, with the first stirrings of Postmodernism and New Urbanism, both of which appealed to me. It’s important to remember that advocating for traditional design was quite radical in those days. I joined a community of like-minded peers—in 1995 The New York Times called us “the young old fogies”—and we knew we had a lot to do to educate ourselves about the rich history of architecture that we hadn’t been taught in school. I took a course on the Classical orders with architect Alvin Holm at Henry Hope Reed’s Classical America, and it was the desire for more that led to the creation of the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art in 1991. I was one of the ICAA’s early founders, a longtime board member, and co-chair of the committee that oversaw the publication of the journal The Classicist. I also planned a number of conferences for the Institute, including the memorable two-day “Reconsidering Postmodernism” conference, with a keynote by Tom Wolfe, in New York in 2011.

Now that you’re practicing independently, what can you tell us about the work you did during your decades at RAMSA?

Over the past several years I’ve been thinking about the many different ways there are to be an architect over the course of a professional career. Working as a design partner at RAMSA was right for me for many years. I was a design partner leading a design studio that was unique within RAMSA, as I was able to take on the widest variety of building types, from houses to academic buildings to hospitality projects and multifamily residential buildings. My completed work at RAMSA represents my distinctive perspective on architecture. I was able to complete a wide variety of houses, including a Shingle-style house in the Hamptons that was published in Architectural Digest. I also designed a variety of buildings on university campuses in styles particular to each institution’s “brand,” including a fitness and aquatics center at Brown University, a restoration-and-addition project for one of the University of Arkansas’s central Collegiate Gothic buildings, and a classroom building and a student center at the University of Portland in Oregon. My completed hospitality projects include golf clubhouses at the Ocean Course and at Cougar Point, both on Kiawah Island, South Carolina; and I was responsible for the design of Courier Square in Charleston, which combines a 70,000-square-foot office building with a 220-apartment residential building. In addition to leading my studio’s design efforts, I was responsible for managing the team and for bringing in new business and working directly with clients. I was also very involved with recruiting the best students from schools with Classical architecture programs, including traveling to career days at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Miami.

What else did you learn in your years at Robert A.M. Stern Architects?

Bob Stern was a wonderful mentor to me and to so many others, leading us to new levels of responsibility and imagination. He taught us the importance of really thinking things through from first principles, of developing a rigorous process of research and exploration and sticking to it, from concept design all the way through to construction details. Bob taught me the importance of a floor plan—as basic as that sounds, he really opened my eyes to it—how to take inspiration from historical precedents, and how to capture the spirit of a place. I learned how to design a house, which is in my view the most difficult of building types and prepares an architect well for success with other building types. Even the 2,700-square-foot house I designed following Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk’s brilliant guidelines for Seaside, Florida (also published in AD), had to fit together like a 3D puzzle—and was the better for it! There was a lot of talent in the office, and I think Bob learned a lot from us as well—he showed us how to graciously integrate others’ ideas into a collaborative design effort.

Bob also taught me the importance of advocating for your ideas and participating in professional discourse: in addition to the ICAA, I have long been active in the Congress for the New Urbanism, the Urban Land Institute, the Society for College and University Planning, and the AIA’s Custom Residential Architects Network.

How do you think you contributed to RAMSA’s evolution during your years in the office?

I believe I played an important role in the firm’s evolution from postmodernism—an essentially modernist approach that referenced traditional design tropes, often ironically—to a more reverential attitude toward traditional design. For example, Bob Stern’s first university project was the expansion of the Observatory Hill dining hall (1984, sadly demolished in 2004) at the University of Virginia, wrapping a Modernist box with new construction that nodded to the school’s earliest buildings by Thomas Jefferson with applied Chippendale ornament. Just a few years later, Bob entrusted me to lead the design of a much larger project at UVA, a new campus for the Darden School of Business. Our winning competition proposal, which was realized in 1996, was a more faithful interpretation of Jefferson’s approach—not just in its architectural expression, but also in its organizational strategy: we broke up the scale of our building by developing our design as a series of pavilions defining lawns and courtyards, just as Jefferson did on the university’s central grounds.

Breaking down a large mass into pavilions, by the way, is a wonderful way to give large buildings—even large houses—a human scale. I and my colleagues carried that approach to other campuses, coming to view their architectural legacy as an important part of their “brand” that our buildings could help strengthen. For example, I led the winning competition design for the Spangler Center at the Harvard Business School, drawing inspiration from the campus’s foundational McKim, Mead & White buildings, and again creating pavilions that tame the building’s size and frame an inviting courtyard. The firm went on to deploy that same strategy on dozens of campuses across the country.

What have you been focusing on as you launch your new practice?

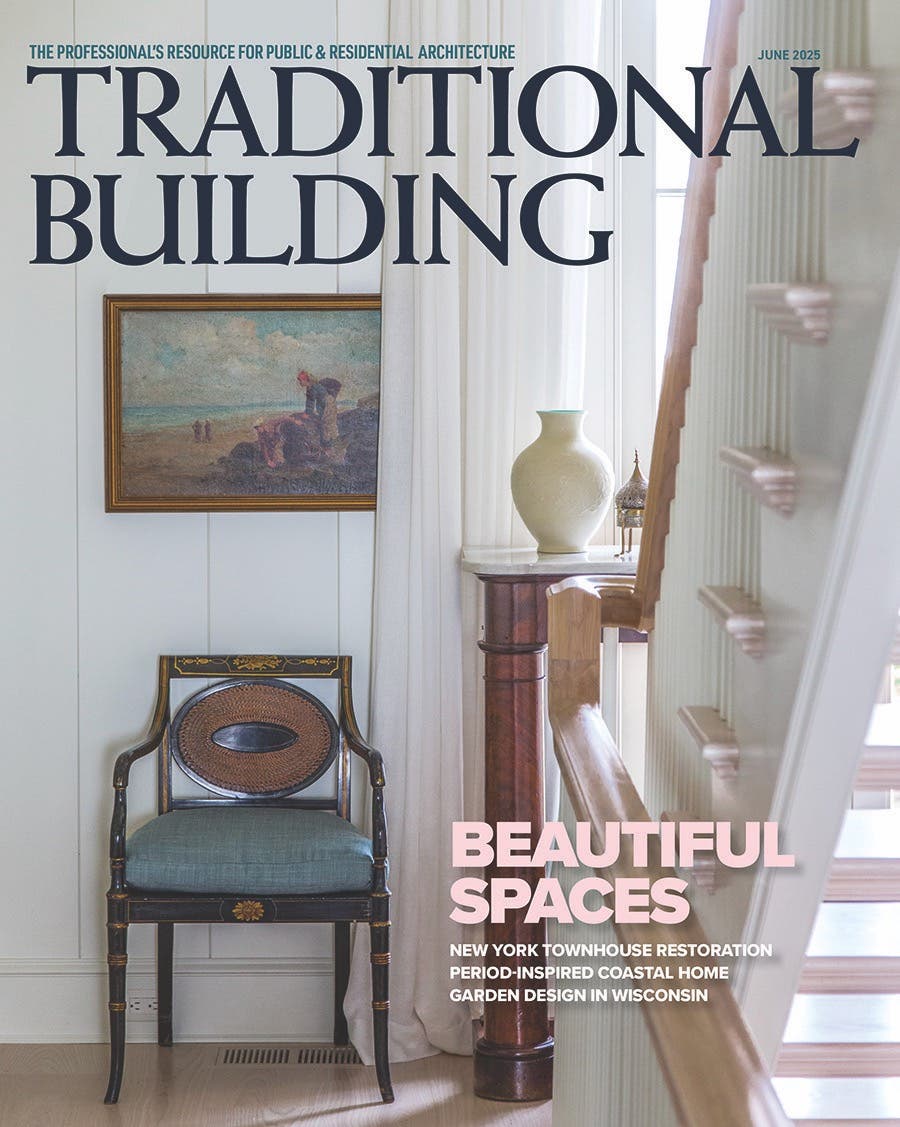

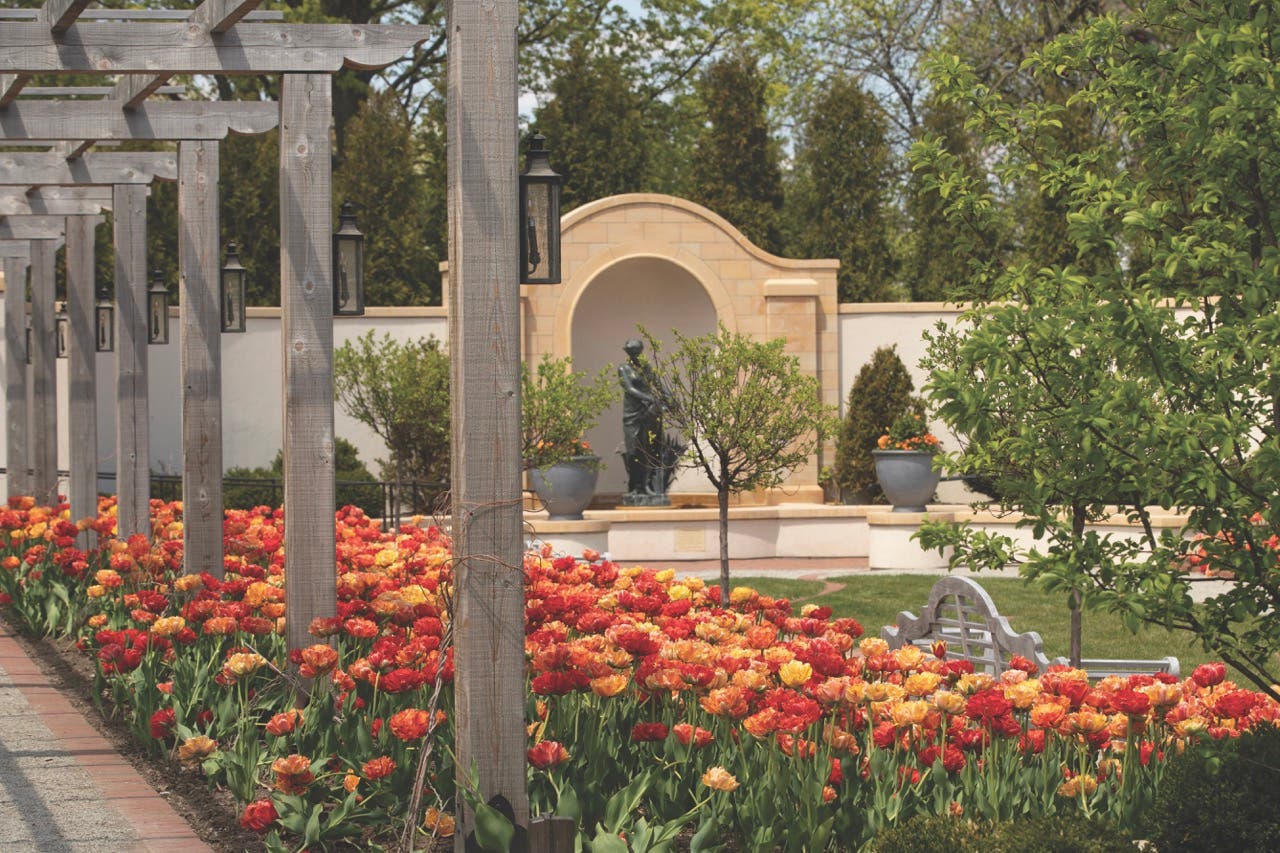

With my independent practice I hope to continue to design all the many building types I worked on over the course of my career to date. Currently I’m working on a Brooklyn townhouse renovation; a historic house restoration in Connecticut; a new oceanfront house outside of Charleston; and a concept design for an apartment building and park for a DPZ-planned community in Alabama. Of course, I continue to tinker with my own classic American Foursquare house, the subject of a recent Homeworthy video—especially the interiors and the gardens.

Other than practice, what have you been doing in recent years?

Mark Ferguson, the Dean of Catholic University’s School of Architecture and Planning, invited me to serve as Classical Concentration Visiting Critic in the fall of 2024, and though I’d often served on end-of-term school design juries in the past, I’d never led a design studio. It was a refreshing challenge. The school also mounted a public exhibition of my work and gave me the opportunity to present a lecture on the history of the American preservation movement to the entire university community.

My studio assignment was a new visitors’ center at Untermyer Gardens in Yonkers, New York, a Classical- and Persian-inspired now-public park designed by William Welles Bosworth with a central garden based on ancient precedents—I’m very interested in teaching students and illustrating to the greater profession how to design buildings that are appropriate to very specific places, and in particular, projects that combine preservation with new construction.

I’ve also been doing a good deal of traveling this past year, giving myself the luxury of seeing places where I’m not actively building—architectural tours of Prague and the Netherlands, where I focused on the work of the Amsterdam School, and then to Egypt and South America. Travel has helped clear my head and renew my focus on history, urbanism, and building design. I hope to visit Lake Como this summer, participate in the ICAA’s drawing tour of Verona, and then spend some time in Rome. I believe it’s important throughout one’s career to seek out new inspiration and learn from the past.

I’ve also focused on creating a website to present my new practice—garybrewerarchitect.com—and I’ve been approached about a book.

How will you work with collaborating architects and other design professionals in your new endeavor?

For my houses, I always work closely with my clients and their interior designers and landscape architects. For houses, I’m happy to collaborate with other architects, and I also have a team of people I can work with on my own. Alternatively, I’m now free to help clients with concept designs that can then be taken forward by others.

To pursue larger work—multifamily buildings for developers, for example, or university or hospitality projects—I’ve been approached by firms interested in supplementing their portfolios with my broad experience, and I’m happy to collaborate with them, as I often did at RAMSA, where a lot of my work was realized in association with architects-of-record, often local to the project at hand.

I’ve been a faithful longtime reader of Traditional Building, which is an important publication and resource for the traditional architectural community, filling a void in the discourse with articles, awards, and inspiration. I invite your readers to check out my website, and I look forward to future opportunities to work together with like-minded colleagues. TB