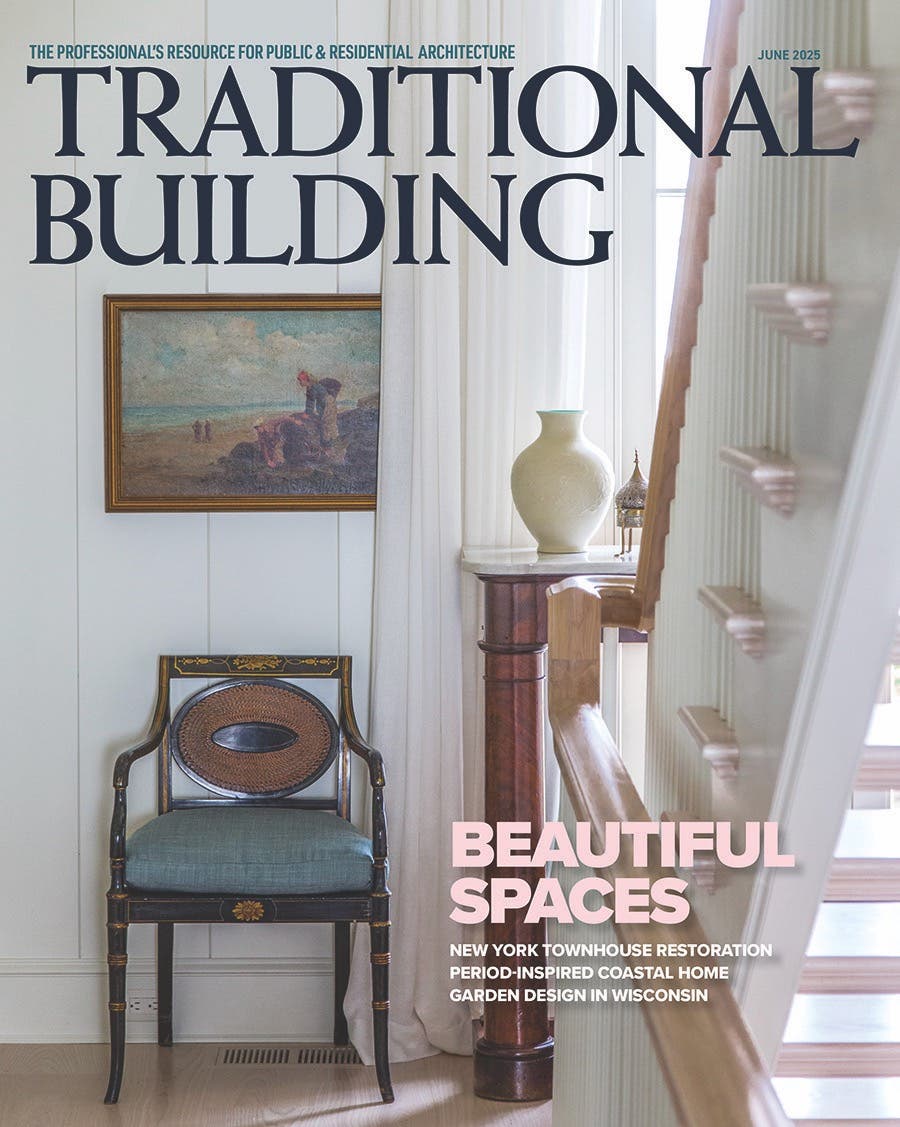

Materials & Methods

The Spirit in the Thread: Merida’s Art-First Approach to Rug Making

hands at work behind the loom.

Credit: Photo by Jared LeedsOn any given day, the 40,000-square-foot textile workshop hums as 25 artisans use natural yarns and an array of equipment—jacquard looms, dobby looms, robo-tufter—for the quiet, effortful work of weaving rugs by hand. Instead of a factory floor grinding against faster-faster-faster mandates, the pace is intentional, bordering on meditative.

Right, Chrome (2024) by Sylvie Johnson in Maison La Roche.

Photos by Richard Powers

“We really were a manufacturing company,” Connolly says. “We’re not a manufacturing company anymore.”

Eighteen years into the company’s second act, Merida embraces a design-driven approach to high-end rug making, elevating natural, sustainable materials and the efforts of its tiny coterie of expert craftspeople. In materializing the concepts emanating from the mind of artist-in-residence Sylvie Johnson, the brand places an abiding emphasis on process over product. “We’ve moved toward works of art that express things, that have depth and life,” Connolly says. “It just took time.”

Initially headquartered in Syracuse, New York, as an importer of sisal wallcoverings for Mormon churches, in 1978 Hiram Samel purchased the company and developed novel methods for cutting and binding sisal into elegant rugs. For nearly 30 years under Samel’s leadership, Merida thrived as a manufacturer and wholesaler to carpet retailers. But by the 2000s, with a flood of foreign-made imitation sisal rugs hitting the market and the essentials of Merida’s business model on shaky ground, Samel sought help from Connolly, an acquaintance and a CEO for a telecommunications market research consultancy who was mulling a career pivot.

Connolly was immediately taken with the company’s employees and its craft-first ethos. Sustaining its craft-first spirit, she thought, meant a shift from manufacturing toward creating a true artisan textile workshop with a direct line to its customers. “I wanted to do something original and provide designers and customers with an experience that’s unique, focusing more on creating an experience than selling a product,” says Connolly, who took the helm in 2007.

By 2010, Merida had centralized its production in Fall River, a scrappy city on Massachusetts’s South Coast with a rich but receding textile-manufacturing history. “Most of the big mills have closed, but the DNA of textiles and of weaving is there, and I’m not alone in hoping to be part of the ecosystem that supports manufacturing of all kinds in this incredible area.” Connolly also connected with Sylvie Johnson, a Paris-based weaver with an overflow of ideas and unmatched design sensibility, to lend the brand a new creative identity. “She heard my intention to create something extraordinary,” Connolly says, “and she is extraordinary.”

Drawing on the blend of elegance and restraint embedded in Johnson’s designs, the company uses all-natural materials like wool, linen, jute, and mohair to create pieces from yarns dyed specifically for each order. Their Studio Series offers a curated range of versatile designs that bring texture and dimension to everyday interiors, while the site-specific, limited-edition pieces that comprise the Atelier Collection are even more elevated, with sculptural weaves and tonal palettes tailored for high-concept spaces.

The concept for each piece stems from concepts created by Johnson, who splits her time between Paris and Fall River and communicates with the workshop daily throughout production. “I came from the world of market research, where you figure out what the market needs and you make it. Here, we are doing the opposite,” Connolly says. “We’re saying: Sylvie, what’s on your mind? What are you trying to accomplish with the yarn, with the series, and with our talented craftspeople? If we’re going to provide something original, we have to be intentional about where the ideas are coming from, versus, ‘Okay, they need more round rugs.’”

boundary-pushing splicing techniques used in this

year’s Atelier works. Photo by Richard Powers

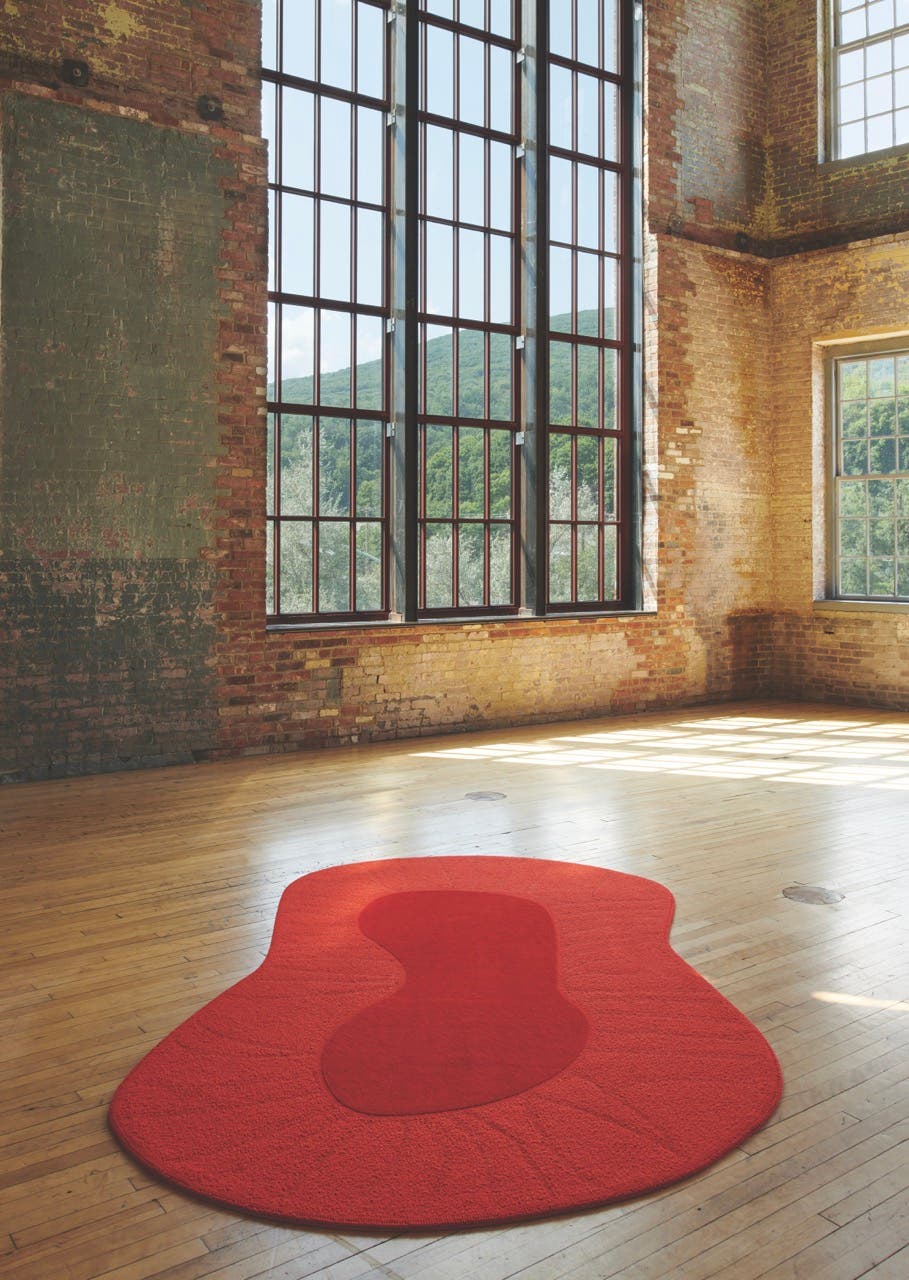

Right, Reef (2023) by Sylvie Johnson in MASS MoCA.

Photo by Richard Power

Along with coordinating summer apprenticeships with local high school students, in recent years Merida has instituted an apprentice-to-master-craftsman program to bolster its local pipeline of artisanal weavers and pass along essential knowledge. “It takes a long time to develop the skills and talent, but it also shows in the work.”

In an enterprise that foregrounds creativity and innovation, that perspective is essential. Connolly talks about the idea of “opening the space in our minds and our lives for experiences that reverberate deeply”—the seemingly simple meal prepared by a chef for every step between the soil and the plate, the furniture crafted by an artisan who spent decades developing an eye for imperceptible details.

“It’s ineffable, but people feel it in the rug,” she says. “That’s what distinguishes this level of work: everybody puts a piece of themselves into it, and you feel the joy and the spirit of the maker.” TB