Religious Buildings

Saving St Jude-on-the-Hill

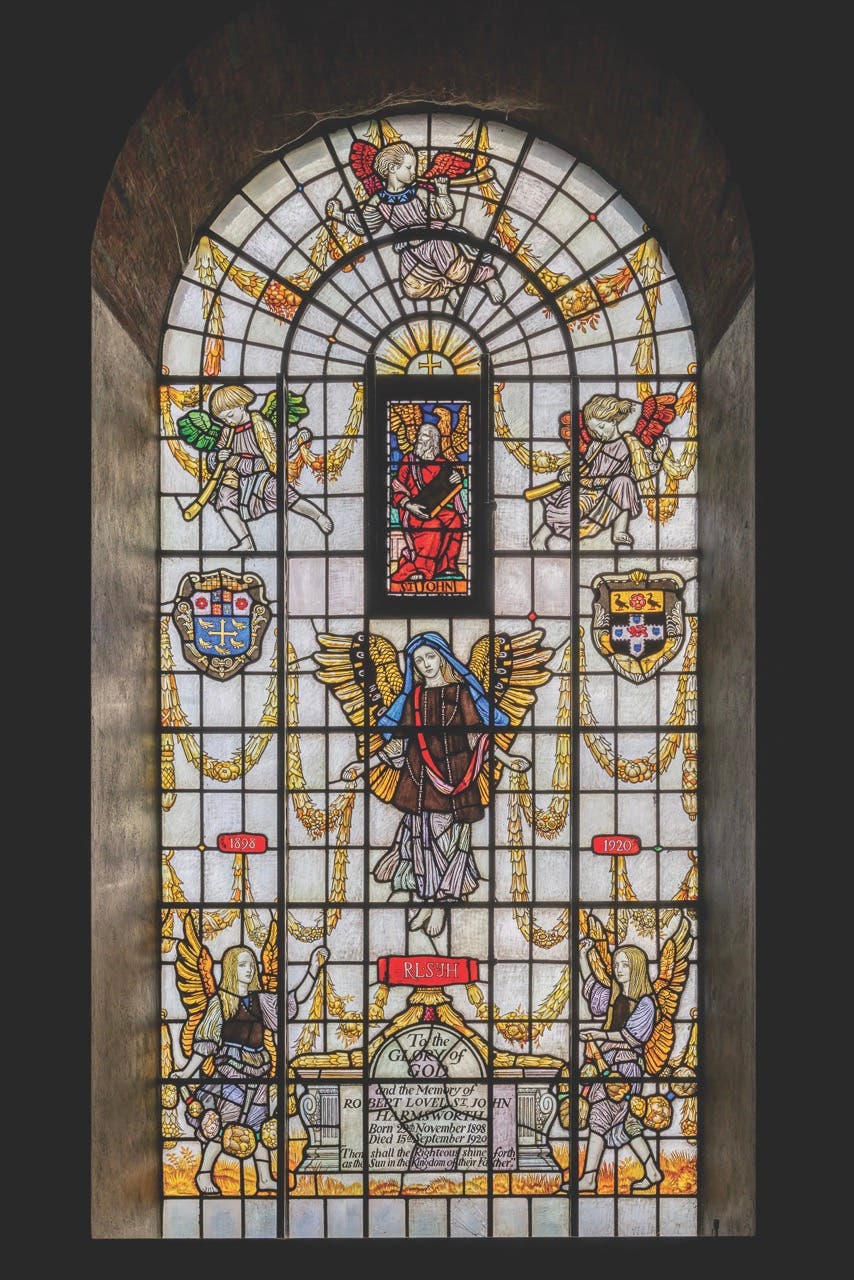

If a lay person were to wander into St Jude-on-the-Hill in north London’s Hampstead Garden Suburb, they would likely see a “beautiful traditional church,” says David Andreozzi, a Rhode Island architect and secretary of The Lutyens Trust America.

But, Andreozzi says, if he were to bring three architects to the building, designed by British architect Edwin Lutyens and consecrated in 1911, they would stare up in amazement, awestruck by unusual details: flat-roofed dormers placed unusually low on the building; blind recesses with mannerist arches; and a whimsical interplay with the Free Church, also designed by Lutyens, across the Central Square.

“Even as architects, it is a next level of architectural genius.” Andreozzi feels that when seeing his work, “He is almost playing with architectural language, completely unconfined by traditional and classical orthodoxy, yet respective of connecting to its cultural soul. Everywhere, he seems to reinvent modern and traditional archetypes, painted together with the same brush.”

Often cited as the most important British architect since Christopher Wren, Lutyens had a hand in more than 800 projects, in styles ranging from classical to Arts and Crafts, often with surprisingly modern touches. The Central Square development at Hampstead Garden Suburb, which also includes a building that now houses a prestigious, non-fee girls’ school, was meant to be the anchor of the planned community. But decades of deferred maintenance have left St Jude’s in a precarious state. Murals are cracking, the floor is buckling, and the heating system recently failed midwinter. Without significant support, advocates fear that the building—and an important piece of Lutyens’s legacy—could be lost.

Rev. Emily Kolltveit arrived at the Church of England parish around two years ago, tasked with helping decide whether there was any future for the struggling church. She found a parish with no treasurer, no churchwardens, and a small group of deeply committed congregants. But she also felt an instant bond with both the building and the community it was meant to serve.

“The first time I walked into the church, my heart just soared out of my chest, because it is the most extraordinary building,” Kolltveit says. “I don’t think I’d ever seen anything like it before, and I felt an instant connection—a calling to serve this parish and see if I might be able to sort out some of the problems.”

‘The First Starchitect’

Robin Prater calls St Jude “an architectural marvel.” She studied Lutyens in graduate school, and today she is the executive director of The Lutyens Trust America, which was founded in 2018. The group works closely with The Lutyens Trust (UK), itself founded in 1984, to celebrate the legacy of Lutyens, whose work spanned five decades between the late 1880s and the mid-1940s, and who is widely regarded as bridging the gap between traditionalism and modernity.

“He’s the first ‘starchitect,’” Prater says. “People wanted to get him to build their houses, even before the First World War. But he was always doing things in his own way. I think he had that in common with Frank Lloyd Wright—that he was able to convince his clients to see his vision.”

“On one level, he has an immense respect for history and tradition,” Andreozzi says. “And on another level, you begin to realize that he was trying to modernize traditional architecture all the time. He was always playing with nuance, reinterpreting things, and thinking outside the box. Personally, I feel he was toying with his fellow architectural brethren, and us in the future, asking us all to not be constrained by only the theoretical… but to think empirically and step up our games.”

Despite the breadth and importance of his contributions, Lutyens was relatively overlooked until the 1980s, perhaps helping explain why a building like St Jude—his first and largest completed church—was neglected for so long. St Jude-on-the-Hill is nearly 200 feet in length, with a spire that tops out at approximately 186 feet. The altar is thought to be the only one in the world personally designed by Lutyens. More than 1,100 square meters of murals cover the interior walls, although these were added later by English artist Walter P. Starmer.

Prater cites the interplay between St Jude and the Free Church opposite the square as a prime example of Lutyens’s wit and creativity. From the outside, St Jude at first appears to be the more traditional of the two buildings, she notes, but its interior appears “more Byzantine,” with a series of domes. The most notable feature of the Free Church’s exterior is a central dome, but once inside, visitors are greeted by classical columns. “He’s playing even between the two churches,” Prater says.

On the Precipice

Kolltveit calls the church’s heating system failure a “shot across the bow”—a warning that steps must be taken to restore St Jude and other nearby Lutyens buildings before it is too late. The floor of St Jude alone, she says, will likely cost more than 1 million British pounds to repair, with the entire St Jude restoration estimated at 5 million pounds.

“It’s significant money that we are looking for,” Kolltveit says. “However, I think that kind of money is fitting for the importance of the building.”

In addition to restoring St Jude and the Free Church, advocates are hoping to eventually tear down a hidden community building that was constructed much later than the rest of the square and replace it with a multi-use community hub and café to serve the wider community and draw people into the area.

Anglican churches are self-funding, meaning it is unlikely that St Jude will be able to obtain the restoration money from the Church of England. The building is known to have some of the best acoustics in London, and the congregation raises a significant portion of its annual revenue by renting out the space for classical recordings. On New Year’s Eve, the church hosted 600 people for a party—“a proper Rave in the Nave,” Kolltveit says.

Although plans to raise money and restore the church remain loose, Kolltveit says St Jude is far from a lost cause. “I think we’re absolutely on a roll,” she says. “But we do need allies. We need experts, and we need people who are passionate.”

“Lutyens did a lot of projects, each one needs to be preserved,” says Andreozzi. “They’re on the precipice. If we don’t do something, as guardians and patrons, we’re going to lose these magical buildings.” TB