Theaters

New Life on Canal Street: The Saenger Theatre is Restored

By Nancy A. Ruhling

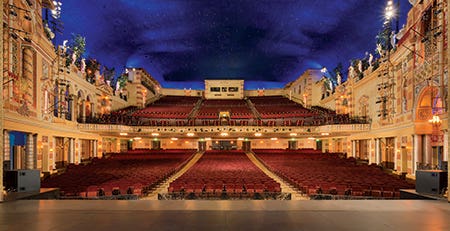

When the ill winds of Katrina blew New Orleans apart, they ripped out the heart and soul of the Saenger Theatre, an iconic and historic movie palace/entertainment center that was much beloved in the community. The 2005 storm literally “drowned” the historic landmark, which, when it opened its doors in 1927 on Canal Street, was the flagship of the celebrated 300-theater Saenger chain. Even in its day, it was a rarity. It’s an atmospheric theater: The intricate Disneyesque interior is designed to give theatergoers the illusion that they are in the great outdoors.

Unlike many historic theaters that have required saving, the Saenger, which was owned by ACE Theatrical Group, was going on with the show even though its small stage severely limited the types of productions that could play there. It became a favorite on the circuit of Broadway touring companies.

“Because of the storm damage, it opened up the opportunity to look at the theater in a whole new perspective,” says architect Gary Martinez, FAIA, principal of Martinez + Johnson, which has offices in Washington, DC, and New York City and has made a mark for itself in the restoration of historic theaters. “Ultimately, it gave us the opportunity to expand and enlarge the space.”

The renovation and restoration became possible when ACE donated the theater, which was shut down for eight years after the disaster, to the city in 2011. A private-public partnership comprised of ACE, the city and the Canal Street Development Corporation financed the project with expanded federal and state preservation tax credits, New Markets tax credits and state tax credit programs aimed at the economic recovery of the cultural and entertainment arts in New Orleans.

“We were happy to turn the Saenger over,” says ACE CEO and president David Anderson, who, with his partners, has restored more than 40 theaters in the last three decades. “Doing so allowed us to make it bigger and better than ever. It’s now the showplace of the South.”

Amenities, amenities, amenities

The biggest challenge of the project was adding patron amenities, including bathrooms and a comprehensive concession stand, while preserving the building’s historic character. Designed by architect Emile Weil, the Saenger, which is centered around two public arcades that form a T-shape, was built in two phases. The entrance and east-west façade of the 4,000-seat theater were completed in 1924, the cross north-south arcade was added in 1925, and the first performance was applauded in 1927.

Designed for silent movies and dramatic and musical performances, it houses a 2,000-pipe Robert Morton organ. The theater’s intricately intoxicating decoration required meticulous restoration. There’s a sky with twinkling stars, drifting clouds and a rising and setting sun as well as false façades, fountains and flowering plantings wrought in the rich ornament of statuary, metal grillwork, urns and painted plasterwork.

Once the financing was in place, it took a year to pump out and dry out the interior, where the water rose 8 ft. above the stage. “This was a monumental task,” Anderson says. “New Orleans is 3 ft. below sea level, and after Katrina, you could see boats floating by the theater. The water under the theater was 25-ft. deep.”

While this work was being undertaken, the scope of the project grew. The street behind the theater was closed off to provide extra stage and dressing room space as well as a loading dock, and the neighboring 20,000-sq.ft. building, which had been home to a Popeye’s fast-food restaurant, was bought and transformed into a concession stand, offices and bathrooms. Stairs and an elevator also were added in this nondescript, adjacent building.

“We had to excavate the street to enlarge the stage, which projects 16 ft. out into it,” Anderson says. “And we had to tear out the old wood pilings, which had been there since the theater opened, and put new ones in the middle of the street. Nobody had ever dug up that street before; the contractors and engineers were petrified.”

Martinez adds that the new stage was so much larger – it is 95 ft. tall and 50 ft. deep as opposed to the original 65 x 34 ft. – that extensive studies were conducted to ensure that it could be supported within the framework of the original building.

The interior and exterior of the theater were restored, as were the public interior arcades, foyer lobbies and audience chamber. The outside façades, which included decorative masonry, terra-cotta elements, sidewalk canopies and wrought-iron work, were rehabilitated, and new marquees, poster boxes and storefronts were designed to continue the vintage theme. The escalator, a decades-old obstructive addition, was removed.

The attention to detail is evident in every detail.

Although new seats were produced by Irwin Seating Co. of Grand Rapids, MI, and Altamont, IL, Martinez + Johnson salvaged some of the original decorative end pieces and made molds so each row would be finished in vintage style. The original iridescent wall and ceiling colors, too, were researched and re-created and then clear varnished as they had been in 1927.

“The trick was to build into the venue amenities people today expect and not have it look like it was two different buildings,” says Martinez. “Before we got the extra building, we were challenged.”

The seating layouts, acoustics, lighting and front-of-house units were upgraded, and the soft finishes were executed byEvergreene Architectural Arts of New York City and Oak Park, IL. The historic ornamental lighting, which includes crystal chandeliers, was restored, re-lamped and reinstalled. Schuler Shook, which has offices in Chicago, Dallas and Minneapolis, also designed more than 40 missing historic fixtures and chandeliers that were fabricated by St. Louis Antique Lighting Co. of St. Louis, MO.

“We wanted to honor the history of the building,” Martinez says. “We relied upon old photos, and working under the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation of Historic Buildings, the historically significant spaces and their finishes were meticulously studied to determine the best process for rehabilitation.”

When the Saenger reopened in 2013, it was to great fanfare. People laughed. People cried. They hugged each other. And Mayor Mitch Landrieu called it the “best symbol of resurrection, redemption and resilience of building the city, not the way she was but the way she should have always been.”

The night, according to Martinez, went on and on as only it can in The Big Easy. “It was the first major remake of a cultural institution on Canal Street,” he says. “It was extremely satisfying to see the healing that was going on.”

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.