Restoration & Renovation

An 1853 Clock Tower Restoration by Campbellsville Industries

The people of Winchester, Kentucky, can’t help but look up to the Clark County Court House. The showy Greek Revival structure, whose clock and bell tower is topped by a golden dome and a shining sword-of-justice-like finial, is the tallest building in the city.

Built in 1853 and added to the National Register of Historic Places 120 years later, the courthouse, home to the Circuit Courtroom and the Family Courtroom for the Administrative Office of the Courts, is the centerpiece of Winchester’s downtown.

Sadly, after more than 160 years, its wooden clock tower had deteriorated.

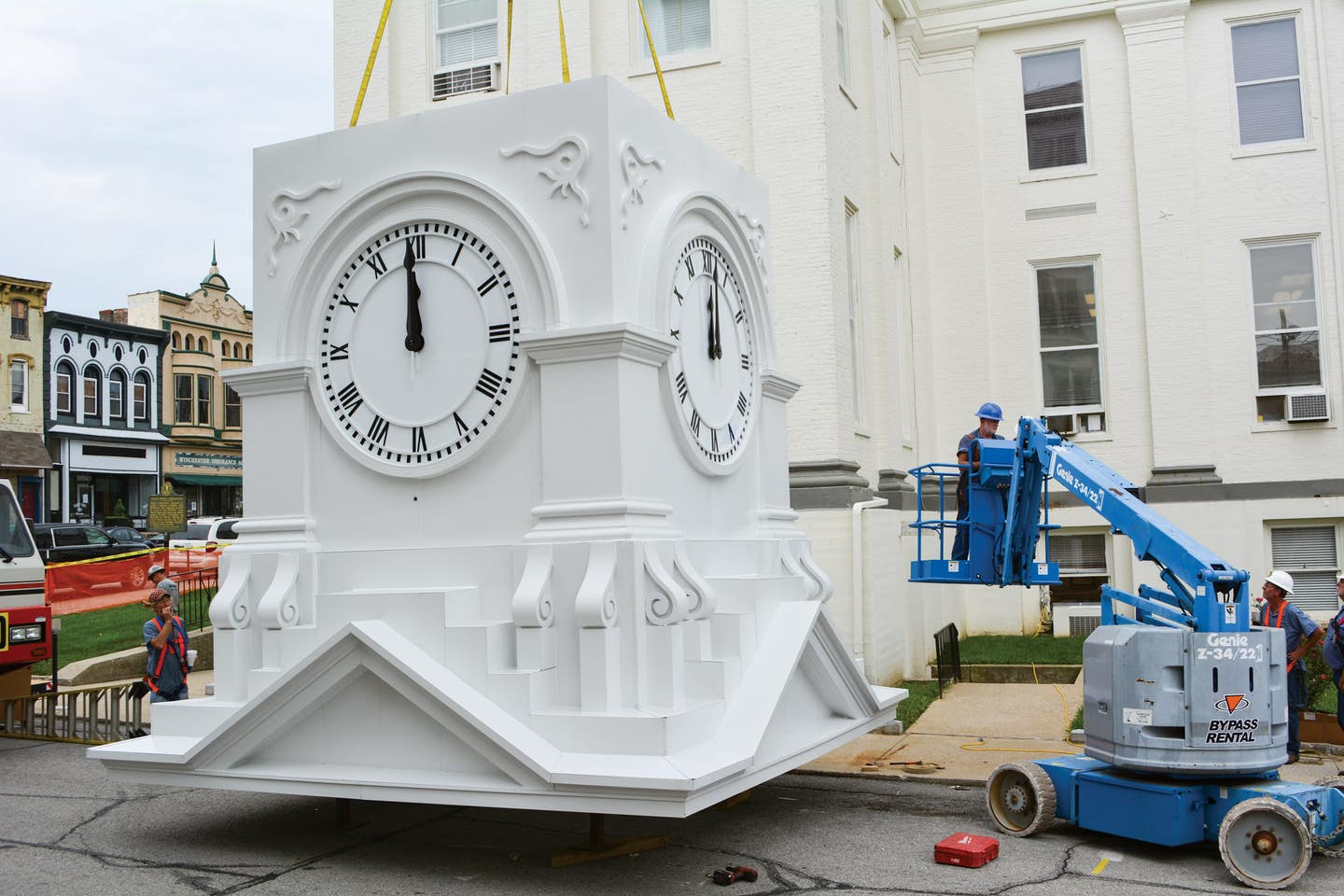

In 2017, the tower, which weighed over 30,000 pounds and stood 165 feet tall, was removed and replaced with a prefabricated steel and aluminum replica manufactured by Campbellsville Industries of Campbellsville, Kentucky. The company, which was established in 1955, has made a name for itself as the oldest and largest steeple maker in America. Nicknamed “The Steeple People,” the firm’s 19,867 projects include the 229-foot spire for the First Baptist Church of Huntsville, Alabama, which was listed in the 1990 Guinness Book of World Records as the “world’s largest prefabricated steeple.”

Campbellsville Industries, which also manufactures domes, dormers, clocks, louvers, columns, cornices, balustrade railing, weathervanes, towers, and other custom architectural metalwork, has executed a number of major public projects, including replicating the historic illuminated clock tower at Hoboken Terminal in New Jersey.

To ensure the historical accuracy of the Clark County Court House tower, the company worked closely with the Kentucky Historic Preservation Review Board. David England, co-owner and president of marketing and sales for the company, says that it was an important project for the town because its towering presence on the skyline has served as “an architectural exclamation point” for generations of residents.

“So many courthouses and churches don’t replace towers and steeples because they don’t have the budget,” he says. “So it’s kudos to Winchester.”

The Process

Campbellsville Industries’ manufacturing process, which marries old-world craftsmanship with new-world materials, cuts not only costs but also construction times. “In the 19th century, when this tower was built, everything was wood and whitewashed,” says England. “It was expensive to paint and hard to get access to. We use heavy aluminum with a baked-on finish that doesn’t need maintenance for years.”

England and his team based their initial damage assessments on film footage from a drone and gathered precise measurements when the clock tower elements were removed and stored. “Using a drone to get accurate conditions of the clock tower is much easier than when I used to work from a man basket hanging from a crane with high winds whipping in my face,” he says. “It’s also much more accurate.” The CAD drawings took a month to complete, and fabrication continued for 18 weeks more.

Campbellsville Industries made the tower’s LED-illuminated clock faces as well as the architectural columns, louvers, balustrades, railings, and dome from aluminum.

“People are always amazed that we start with flat pieces of aluminum and turn them into decorative details such as hand-fabricated cornices and pediments,” England says. “Everything was replicated properly and is historically accurate. We even made faux stone blocks to match the rest of the building. We left space between each to simulate grouting.”

One of the more challenging aspects of the project was the dome, whose structural aluminum angle is clad in heavy-duty .032-inch aluminum with a 23 ¼ karat gold leaf finish. “It’s not ornate, but it caused a fabrication problem because of its tapered and rounded design,” says England. “We worked hard to bend the aluminum with compound bends to get the rounded shape right, and we made several mockups to show the county for approval before one technique was selected.”

The team also took great pains to make the dome look historically accurate. “The original craftsman beat and hammered copper in a crude fashion, and the fabrication was not up to modern standards,” England says. “We were able to get exactly the same shape and also have it look aesthetically pleasing.”

An anonymous donor paid for the gold leafing of the dome and finial. England, a member of the Society of Gilders, applied the tissue-thin 3 1/8-inch squares of 23 ¾ karat gold to the dome’s surface, which covers 23,000 square inches, and to the 6-foot-5-inch-high finial.

“It took me an entire week to put on all 2,556 square inches of gold,” he says, adding that if there’s a single hole or “holiday” in the gold leaf tissue, it has to be patched. “I worked from early in the morning until late at night. I did one 10-hour stretch. My shoulders and arms were sore for a week.”

The four clock faces, including numerals, rings, and tick marks—which are illuminated with LEDs—required equally intricate work: The custom numerals were replicated from the originals and cut out on a CNC machine. England says these and other details, such as the tower’s hand-fabricated louvers backed with insect screens, define the project.

Once the components were finished, they were loaded onto special flat-bed trailers by crane and driven to their destination some 120 miles away. “It was a two-hour trip,” England says. “For the dome, we created plywood windbreakers in the front to stop bugs and debris from damaging the gold.”

Winchester’s main streets, which were laid out during horse-and-buggy times, are so narrow that getting the trucks and crane in was difficult. “They had to block the streets, and we had to work around power lines and utilities,” England says.

Finally, over two days, the pieces were set atop each other like layers of a wedding cake. “Everything was prefit in sections,” England says. “It is amazing to see the coordination of the road crews as they choreograph the different trailer loads in the tight spaces.”

According to England, it’s quite possible that the new tower will last another century and a half. “We like to think that if people in other centuries had access to the same materials, they would have used them,” he says. “At some point in time, if it is to be refinished in a generation or two, the pieces can be disassembled and brought back to our factory.”

England takes pride in the fact that the children and grandchildren of the current residents will be dazzled by the beauty of the tower. Many won’t even realize it’s a replica, which is just the way he wants it. “It’s great to see the community retain its architectural heritage,” he says. “The dome is the crowning element; the brilliance of its gold hits so hard that it’s difficult to look at.”

Key Suppliers

Clock Tower Manufacturer David England, president of sales and marketing, and Rick Green, project sales rep, Campbellsville Industries

Architect Margaret Jacobs, Tate Hill Jacobs Architects

General Contractor William Littlejohn, project engineer, SSRG (Structural Systems Repair Group)

Engineer President Christopher S. Kelly, Poage Engineering & Associates

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.