Windows & Doors

Wood Doors for Historic Buildings

Quality wood doors create lasting first impressions.

By Martha McDonald

Few would deny that an entry door, like a person's face, is one of the most important elements of a building. A visitor looks for the entry when searching for a building, sees it up close when entering, and touches it when entering and exiting the building. And, this happens hundreds, maybe thousands of times a day, in a commercial or institutional setting.

Suppliers agree that wood is an ideal material for an entry door. It offers a sense of quality, warmth and durability. In addition, wood doors can be built to almost any size, shape and style. Look for wood quality, solid-wood construction, joinery, thickness, proven custom capabilities, and hardware, they say, when specifying a wood door.

"Wood is especially important when dealing in the traditional realm," says Michael Iwanyczko, director of marketing, Reilly Windows & Doors, Calverton, NY. "If you are looking for a certain aesthetic and warmth, it's the only material you can use. Imagine a Gothic entry door for a church with a lot of carved details. It would have to be wood."

He adds that wood doors can also be used for skyscrapers. "We are working on a new 20-story limestone skyscraper. All three of the entry doors (main, service and retail) are wood, and all of the windows and doors in the public spaces on the two lower floors are wood, creating great warmth and a richness you can't get from aluminum."

At HeartWood Fine Windows & Doors, Rochester, NY, director Tim Forster agrees. "For years, wood was the only material available for commercial doors. Aluminum only came on the scene 60 or 70 years ago. Wood is still very appropriate for entry doors. It has the greatest ability to be customized to the architecture of the building. It creates a sense of warmth, and is unlike any other building material."

"For a traditional door, wood is by far the most used material,"

Forster adds. "Historically appropriate stops, moldings and panel profiles are only possible with wood. Another option is aluminum, which is not appropriate for a traditional building. Bronze doors can be a beautiful option, but they are very expensive, and heavy."

"Wood has a character that emits warmth and natural beauty that sets it apart from man-made materials," notes Ron Safford, president, Parrett Windows & Doors, Dorchester, WI. "Often the entry door makes a statement about the building. Craftsmen can generate levels of style and beauty in wood that cannot be created with any other material. Furthermore, wood has ecological benefits in that it comes from a renewable resource."

"No other material speaks the way wood does, has the gravitas," adds Steve Hendricks, owner, Historic Doors of Kempton, PA. "Also, wood offers design flexibility in fitting the style of the door to the building. Any style of architecture can find its unique expression in the style of door. Wood is a great material for rendering those different ideas."

Durability is also a key factor. Suppliers note that a properly maintained wood entry door can last for centuries. "I was in Europe a couple of years ago, taking photos of very old buildings, 500 to 600 years old, and they still had the original wood doors," Forster points out. "They were made the same way we make doors today, with mortise-and-tenon construction. Wood can be a very durable product if the door is made properly and is maintained."

"Wood will definitely last for a long time," says Iwanyczko. "Sometimes it looks better as it ages. As long as it is maintained, it weathers with the building."

Durability also depends on where the door is placed. "Modern architecture often gives little thought to the placement of an entry door," says Hendricks. "The best entrance is one protected by an overhang, recess or porch roof. These features also help announce where the entrance is.

"A correctly situated entry will also help protect its finish," he adds. "Finishes of all sorts have to be maintained. The basic difference between modern and traditional finishes is that modern finishes are a plastic coating that keeps moisture in. Older finishes penetrate the wood and act as a preservative. We use a European linseed finish that our clients will be able to maintain."

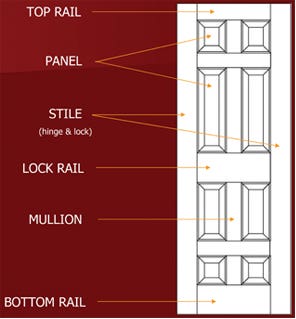

Construction

The construction techniques used to build wood doors have remained constant over the years. Rail-and-stile, stave, and batten are typical historic types of construction still used today. A batten door consists of horizontal boards (battens) set across a set of vertical boards with braces set at an angle.

A solid-wood rail-and-stile (or frame-and-panel) door is considered more stable than batten because it allows the wood to move with seasonal changes. It is comprised of horizontal (rails) and vertical (stiles) pieces that frame panels. Stave construction involves three layers of wood, laid with the grain in opposite directions. The interior and exterior layers can be a facing or a thinner veneer.

Joinery for traditional doors is often mortise-and-tenon, considered stronger than dowel construction. "We believe a mortise-and-tenon construction is stronger," says Forster. "You carve out a pocket and the tenon is a tongue that slides into it. You get a lot more glue surface and overall strength than with dowels."

Reilly and Historic Doors specialize in stave construction. Reilly's Iwanyczko explains that with stave construction, the interior layer can be any wood. "We can do a beautiful, substantial door out of oak, mahogany, teak, old-growth Douglas fir or reclaimed heart pine (not new pine) on the exterior, with cherry on the interior layer."

Historic Doors adds that joinery in a superior door will always be mortise-and-tenon, not dowel. "All of our doors are stave-core constructed with mortise-and-tenon joinery. The core is put together much like butcher block, then you sandwich that core with resawn solid lumber. Stave construction actually has a solid wood skin, not a veneer, and it results in a more stable product. It is really a re-engineered wood."

All agree that thicker is better, especially for commercial applications where the door gets a lot of use. "The minimum is 2¼ in., depending on building," Reilly's Iwanyczko explains. "You need 3-in. doors in a hurricane zone, and for bigger doors – a 4-ft. wide x 10-ft. high, for example. A door normally measures 3 x 8-ft."

"Most commercial doors are 2¼ in. thick," agrees HeartWood's Forster. "For larger doors – one architect wanted an 11 ft. tall door – the doors have to be beefy enough to endure the rigors of opening and closing over time. For this particular door, we made the stiles and rails 3-in. thick."

Species

HeartWood specializes in custom solid-wood rail-and-stile doors and works primarily in genuine mahogany from South America. "It is the best species for exterior doors," says Forster. "I would say that 80% of our exterior doors are made of genuine mahogany. It doesn't cost that much more than walnut, cherry or quarter-sawn white oak. The others don't have the same stability and rot resistance."

He adds that while quarter-sawn white oak is also extremely hard and rot resistant, it is not quite as stable in terms of shrinkage and expansion. "Usually, once doors acclimate, which can take from several months up to a year, they tend to stay stable unless there are extreme circumstances." "You need quality wood for institutional and commercial projects," Iwanyczko says. "These doors have to last 100 years. I recommend using old-growth wood that has been dried properly." He points out that the 100-year-plus-year-old doors that still exist are made of old-growth wood which is much more stable than today's new-growth wood.

"Woods vary greatly in performance," says Parrett's Safford. "Some wood species are better suited for certain climates than others. Also, hardwoods, as opposed to softwoods, will provide better protection from impact. In general, woods that are stable and resistant to decay are preferable." Hendricks says that the best species for exterior wood doors are the mahoganies, white oak (not red), walnut and Spanish cedar. "These offer a high weatherability rating," he explains. "All oak is not the same. White oak has a closed cellular structure that doesn't allow water to penetrate."

Hardware

Using the proper hardware for a commercial or institutional wood door is also an important consideration. "Your best bet for the exterior hardware is un-lacquered brass or bronze," says Iwanyczko. "These doors get so abused that the raw metal is best, or maybe a living finish like oil-rubbed bronze or antique brass. You can also take the raw brass and put a chemical on it to pre-age it, but no actual finish.

"The truth is that the hardware will age from use," he adds. "No matter how good the chrome or nickel plating you put on it, it won't look that way in five years. So you are better off going with an unfinished hardware. Over time, it will patina."

"We often use brass and bronze on traditional doors and they are usually coated to create the desired patina," says Forster. "They tend to be naturally aging finishes, like an oil-rubbed bronze, for example. If you are using bronze with a natural finish it will last forever." "Use proper size hinges," he also stresses. "A door that will be cycled a lot, like a restaurant's, requires properly sized hinges for the size and weight of the door. We always recommend premium quality heavy-weight ball-bearing hinges."

Safford agrees. "Use proven hardware that is properly suited for the door system," he says. Hendricks notes that generally speaking, it takes 8 to 12 weeks to fabricate a custom door, including shop drawing and design services. "Certainly, the earlier the better," he adds. He also points out that doors that will be fully exposed to rain should not be built with grooves that capture water. And, he adds that the top edge is often overlooked in institutional doors that swing out into the weather. "This edge should be covered," Hendricks points out. "We usually use copper flashing or epoxy."

In conclusion, suppliers agree that custom is usually the best way to go. "I will often try to get clients to go custom even if they don't have the budget to go custom elsewhere," says Iwanyczko. "We work with them on details to increase longevity, thickness, height, selecting the correct species. Clients often don't understand the amount of abuse that these doors take. If you do it right, that door will last 100 years."

In conclusion, suppliers agree that custom is usually the best way to go. "I will often try to get clients to go custom even if they don't have the budget to go custom elsewhere," says Iwanyczko. "We work with them on details to increase longevity, thickness, height, selecting the correct species. Clients often don't understand the amount of abuse that these doors take. If you do it right, that door will last 100 years."

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.