Product Reports

Fresco Painting Techniques

By David Mayernik

Of all the methods that painters employ, painting on the wall is the most masterly and beautiful, because it consists in doing in a single day that which, in the other methods, may be retouched day after day, over the work already done. — Giorgio Vasari, excerpted from his Lives of the Artists (1568), in Vasari On Technique, Dover

When the Renaissance painter and architect Giorgio Vasari says “painting on the wall,” he was referring to the ancient technique of fresco painting. Many people today use the words fresco and mural almost interchangeably, but while virtually all fresco painting is mural painting, not all mural painting is fresco.

Fresco painting (or in Italian affresco) is painting into fresh (fresco) lime plaster; this is also what Italians have always called buon fresco, or true, good fresco—because there are other ways of working with lime plaster that don’t involve working while the plaster is curing, and these are generally less durable than true fresco. A mural (from the Latin muralis, wall) is any painting on a wall.

Part of the durability of fresco depends on the wall itself—its relative stability (it doesn’t move much, if at all), its capacity to translate and not trap moisture, and how free it is of salts or other damaging agents that can leach through the surface and damage the plaster along with the painting. Indeed, since the fresco is effectively integral to the plaster, the painting is only as durable as the plaster.

While it is the slow-curing nature of the lime itself that enables the fresco process, it is also the qualities of lime plaster—relative flexibility in response to movement or climate change, its ability to translate and not trap moisture—that contributes to the durability of fresco painting. In other words, a solid masonry support using lime mortar, and exclusively lime plaster for the scratch, brown and finish coats, are the default conditions for a durable fresco painting.

The great technical advantage of the fresco medium is, in fact, its long-term durability.

On the other hand, the great challenge of fresco painting is the speed required to accomplish it. Since you must work within the plaster’s curing time—a day’s work, essentially, or a giornata in Italian—and the plaster is constantly changing while it’s curing, you must accomplish your work according to the plaster’s schedule; not to mention that, after an initial hour or two when the lime is quite active on the surface and you can, to an extent, “erase,” otherwise for most of the day (and more so as the day goes on), what you put on the wall you’re stuck with.

This is why Leonardo da Vinci tried to modify the fresco medium in the Last Supper to allow his slower, meticulous working process, to disastrous effect on its durability. Now, lime plaster being an almost living thing, it behaves differently in different climates; so, if you want a long giornata, pray for rain. I’ve worked in dry conditions where I had maybe eight or nine hours to paint from the moment the plastering is complete, to working outside on a cold, rainy April day where I could have painted for almost 24 hours.

The unusual aspect of fresco painting is that there really is no painting medium, or binder per se (like oil)—instead, the medium is, in fact, the lime in the plaster. In buon fresco painting, pure powdered pigments are brushed on simply with water, although some have advocated using lime water (which increases the bond with the plaster but also lightens the colors as they dry). Brushing the pigments suspended in water onto the curing lime plaster surface activates the lime, which bonds the pigments into the matrix of the plaster as the water evaporates.

In true fresco, the pigments become slightly embedded in the surface of the plaster. Part of the sparkle in a fresco then comes from the glistening effects of the plaster’s aggregate—typically river sand, but marble dust may be added, and in Rome pozzolana, or volcanic ash, was common (Michelangelo used it on the Sistine ceiling). Each of these aggregates influences the color of the plaster and therefore the fresco: sand can vary from gray to yellow, marble dust is brilliantly white, and pozzolana has a mauve hue.

It tended to be true historically that fresco was considered a relatively cheap way of covering a lot of wall, or ceiling surface, with paintings. It is also the nature of mural or ceiling painting that the overall effect, seen from a distance, was primary. Speed, conditioned by the medium, economics and context, had inevitable consequences for painting technique.

The Carracci cousins who painted the great Galleria in the Palazzo Farnese worked remarkably differently in oil and fresco. Up on the ceiling, up close, there are aspects that are almost impressionistic, and they allowed—even required—visible brushstrokes in ways they never would have allowed on a canvas. But these are not compromises. This bravura technique is what gives fresco its liveliness, its freshness, its sparkle. But it also demands what Renaissance Italians meant by disegno—preparatory drawing, to be sure, but also design, or composition. Much of what sustains the loose brushstroke of frescoes up close is the way the strong drawing and design carries the composition from a distance.

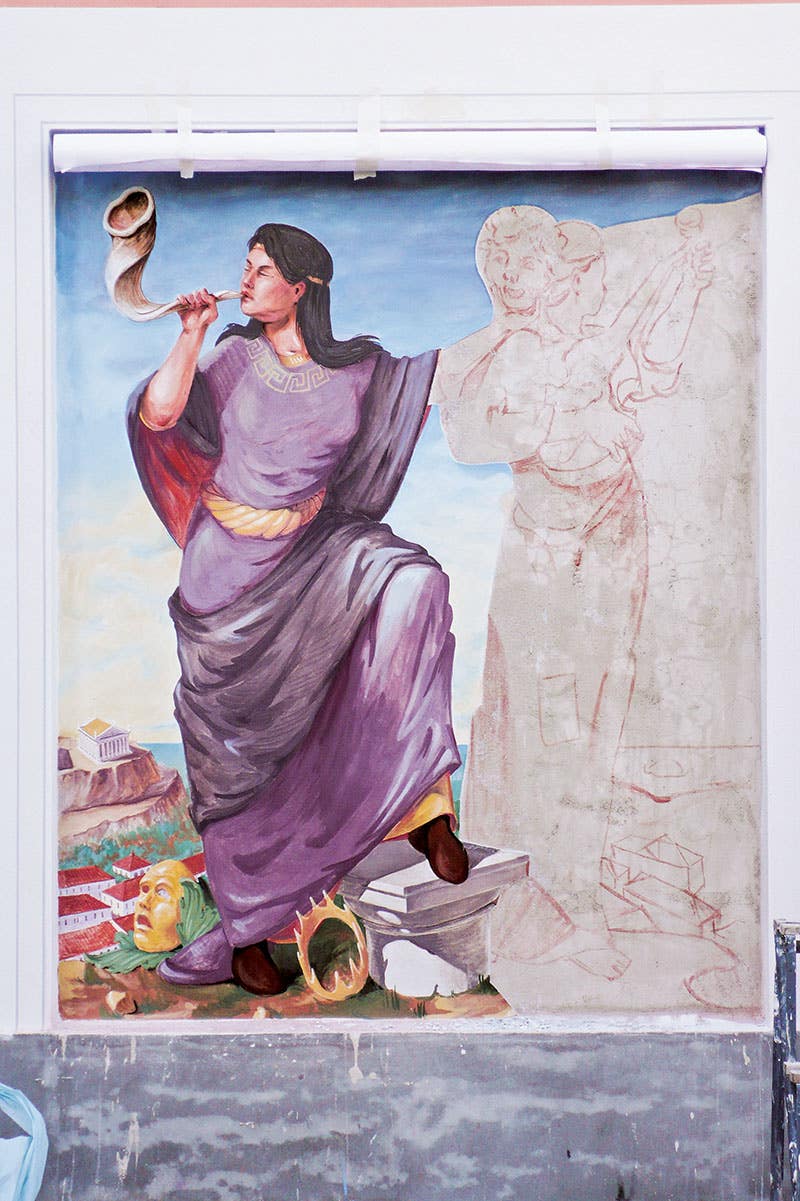

But drawing wasn’t just necessary for the aesthetic effects of the painting, it was essential to the execution because the commitment fresco required demanded careful preparation: first concept sketches, then often an oil color sketch, or bozzetto, and finally the full-size cartoon that was transferred directly on the wall either by punching holes and pouncing, or (the dominant mode from the later Renaissance on) by tracing the cartoon with a stylus and making a slight incision into the plaster surface (incisione). If you look closely, you can still see these incisions in raking light.

Fresco Techniques in Context

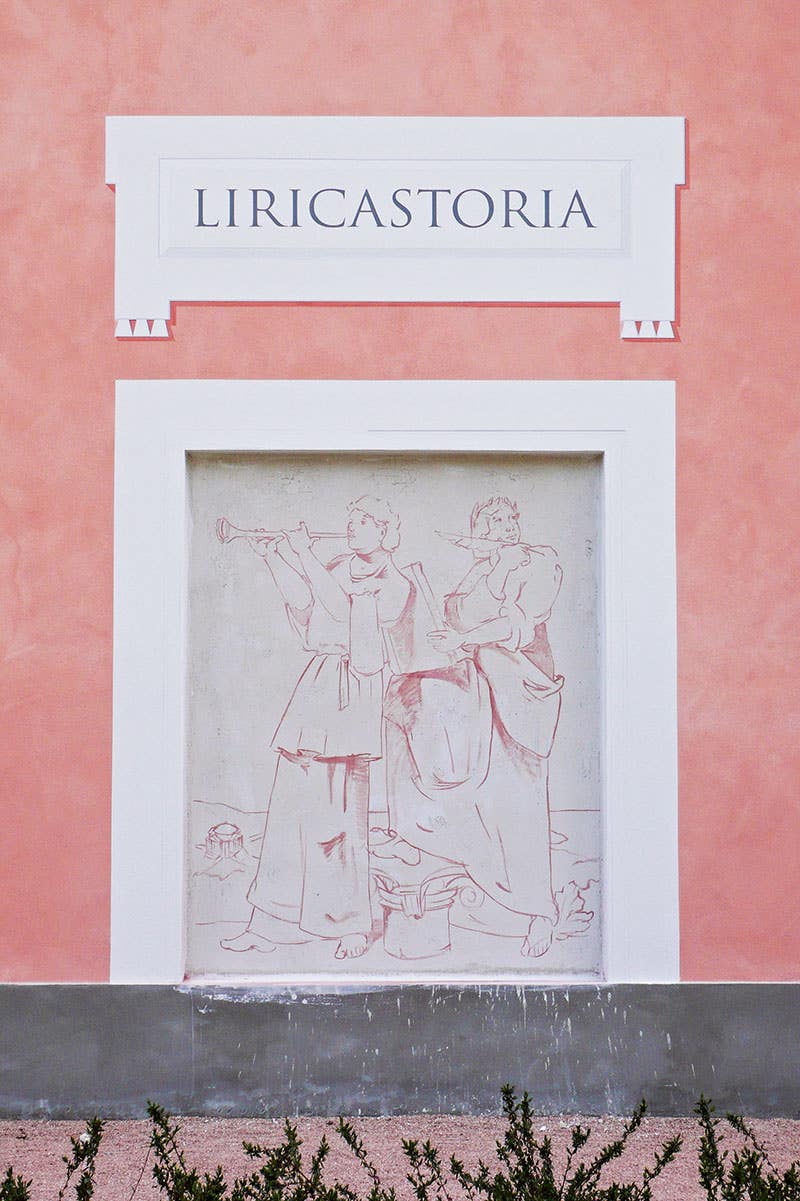

While Italy may be the land of fresco painting, frescoes can be found outdoors even as far afield as Russia; and while we associate fresco with Mediterranean warmth, it is mostly true that only in colder northern Italy do you find a quantity of frescoed facades (there are exceptions, of course, in both Florence and Rome). Outdoors the great enemy of fresco isn’t so much the rainwater itself as abrasion from constant washing, and, of course, the corrosive agents in modern rain. For these reasons anything other than buon fresco is rarely used outdoors. Sunlight doesn’t damage frescoes, since the colors used are all lightfast.

Inside, though, where the environment is less of an issue, artists since antiquity have used other techniques in parallel with, or on top of, buon fresco. One of these is so-called mezzo-fresco, or half-fresco, because you paint with limewater on an already cured plaster surface. The limewater makes a weak bond with the lime in the plaster, the pigments remaining more on the surface than in buon fresco but still bonded like-to-like with the matrix of the plaster.

The advantages of mezzo-fresco are both the extended painting time and the larger expanse of wall that can be covered. Especially large landscape paintings were done this way, where the jigsaw puzzle pattern of giornata seams would defeat the continuity of the scene. Many of the great late Baroque fresco artists, like Tiepolo, preferred mezzo-fresco on top of a buon fresco underpainting to accomplish large ceilings, where figures floated against an expanse of unbroken sky.

Frescoes were often touched up secco, or dry, using some form of tempera paint. This was relatively common in the case of blue, where historically few blue pigments were adaptable to fresco. (Today there are more blue pigments that can work in fresco.) Being a film on the surface of the plaster, however, means that tempera touch-ups are less durable, subject to flaking as their bond weakens, or removal by even light abrasion (historically, frescoes were often “cleaned” with wet sponges, sometimes even varnished to “restore” their brilliance).

Fresco Painting Today

The modern Renaissance of fresco painting can be traced to at least two sources, both in Italy: one being the great 20th-century portraitist Pietro Annigoni, who in later life largely devoted himself to pro bono painting of frescoes for churches around Italy, including contributing to the rebuilding of Montecassino. Annigoni was a great teacher, and his interest in recovering fresco technique was passed on to generations of artists, including a number of Americans, like Ben Long. It can also be traced back to restorers like Leonetto Tintori, who believed that in order to restore frescoes one had to know how they were done, and who also was a great teacher—not only of restorers, but also artists whom he welcomed into the school he set up in his home after retirement. (I was lucky enough to be one of them.)

Today there are a number of artists around the United States, in Europe, and elsewhere, who practice buon fresco painting. Many formed their knowledge on the age-old practice of copying the Old Masters. And it is true, I would argue, that the technique of fresco is associated with a way of painting that we know from ancient Rome, the late Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and Baroque; it is not only a technique, it is a tradition. This ever ancient, ever new, way of painting (to paraphrase St. Augustine) continues to enrich the world’s buildings, and merits our investment in its marvelous combination of durability and freshness.

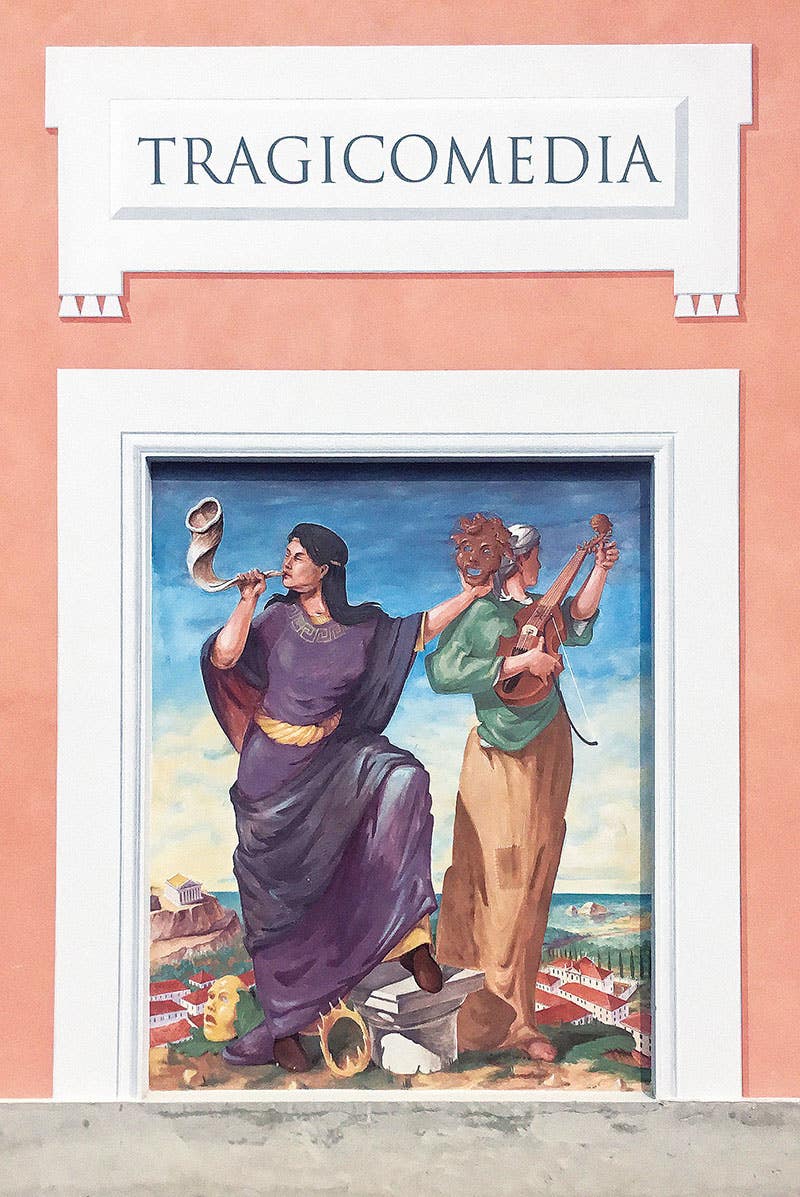

The Theater at TASIS (The American School in Switzerland)

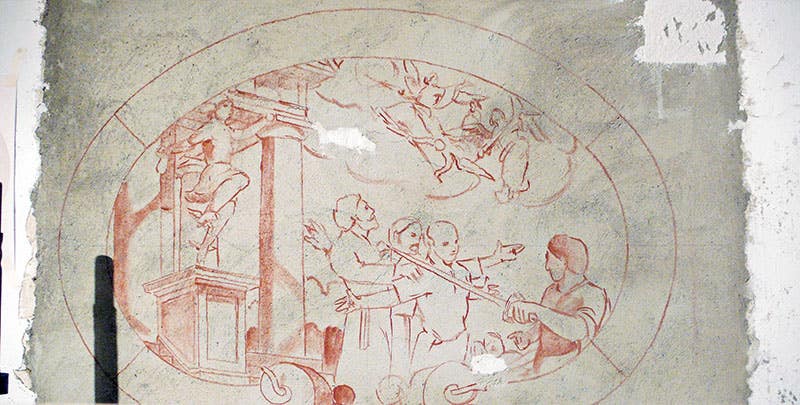

On the arriccio (the brown coat in English), or the plaster coat below the final, finish coat (the intonaco), the artist draws with a brush the sinopia (named for a red pigment from Turkey), which describes the general forms to be painted and functions as a road map for the plastering to be done each day. With each day’s plastering, the sinopia is progressively covered over; it is often mistakenly thought the sinopia functions as an underpainting, but the finish coat of plaster, being opaque, means the sinopia disappears when the intonaco is applied. Medieval and Renaissance sinopias have been found by peeling away the finish plaster for conservation.

Buon fresco paintings are composed of a jigsaw puzzle of days’ work, or giornate, based on what the artist thinks he or she can accomplish in the time it takes the plaster to cure. In painting over the course of the day, the artist works from establishing the broad modeling and subtler tonalities earlier in the day, with smaller, bolder lights and darks added later in the day when the lime bonds the pigments more quickly to the wall.

David Mayernik studied fresco technique with renowned restorer Leonetto Tintori. His first commissioned fresco was for the Library of the American Academy in Rome, where he is a Fellow. Since then he has painted frescoes for the church of S. Cresci in Valcava, in Tuscany, and his own buildings for TASIS, The American School in Switzerland.

For more information on the art of fresco, go to: www.frescotrail.com/resources.html

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.