Product Reports

Bricks: Building Blocks

Masonry consists of units cemented together with mortar such that the individual elements act together to transfer loads. The masonry units can consist of brick, block, stone, or terracotta; only brick will be discussed in this column. Brick can be used for load-bearing applications, veneer cladding, walls, floors, vaults, arches, and decorative elements. It is a versatile material, with a variety of sizes, colors, textures, and bond patterns, which can create interesting details on many levels.

History

Bricks date to 7,000 BC, using sun-dried mud and later, clay. About 3500 BC, Egyptians fired bricks in ovens, and this began the use of clay bricks in cooler climates where sun baking wasn’t possible. During the Roman Empire, bricks were fired by mobile kilns, spreading the use of bricks through Europe. In North America, Taos Pueblo was built with adobe (mud and straw bricks) a thousand years ago. Bricks and masons came to North America with the migration of the Dutch and British in the 1600s, and with the Industrial Revolution came machines for increased production. In the 1900s, concrete blocks and bricks went into production after the invention of Portland cement.

Current Production

Bricks are formed from clay and placed in a drying shed to reduce the moisture sufficiently for the bricks to be fired. Before the advent of modern kilns, which move the air through the kiln for more even heat, old kilns had uneven heat that resulted in a variety of brick strengths: Black-heads, which were closest to the fire, picked up a black skin from the soot from the fire and were well vitrified. Red stretchers were close to the heat, evenly fired and the strongest. “Salmon” brick—those farthest from the heat—were soft and porous, did not vitrify well, and were typically used only on the interior of a building.

By contrast, concrete bricks, having a chemical strengthening process, are formed and left to cure.

Characteristics of Brick

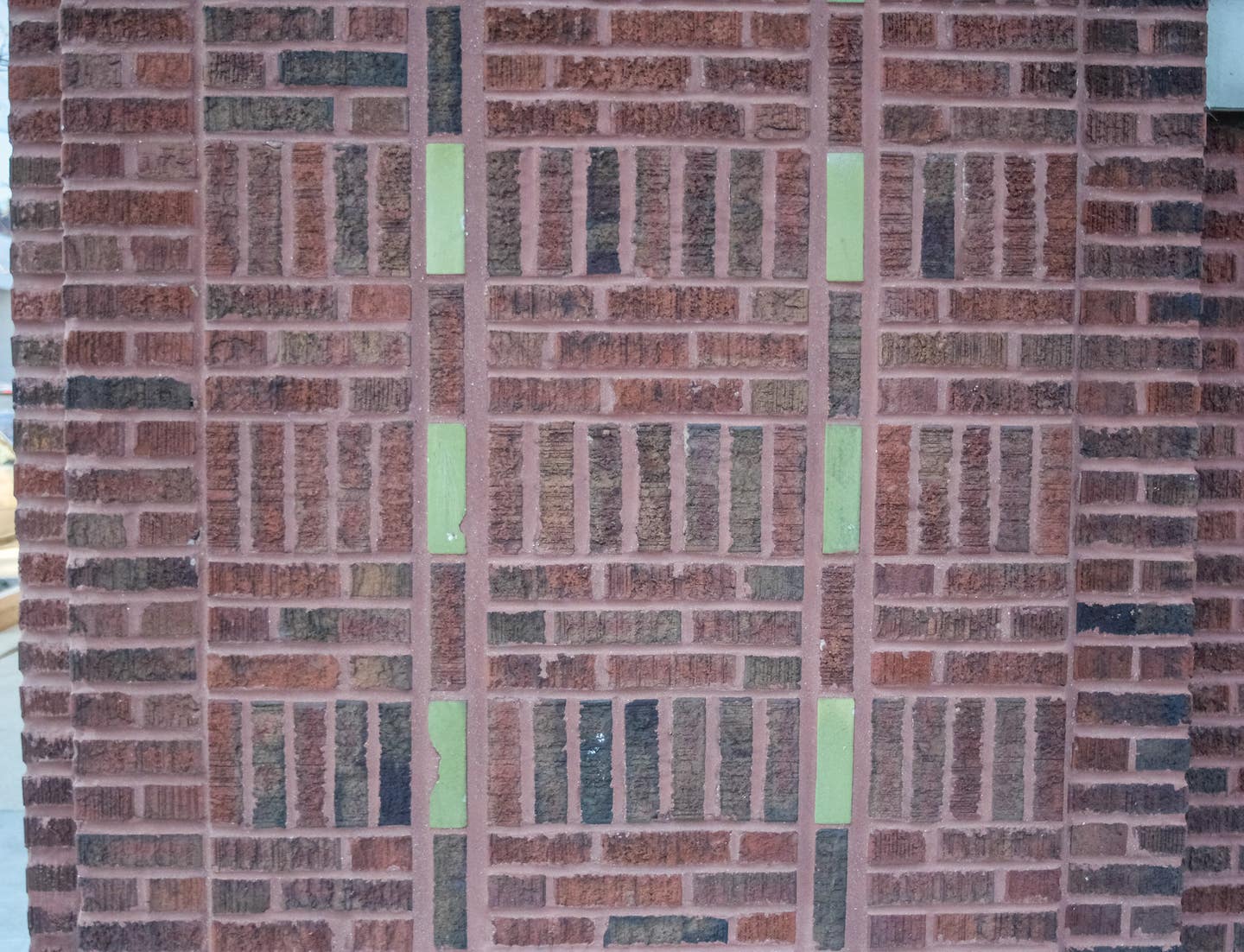

When repairing a historic structure, new bricks need to be carefully matched for all their properties. This includes color, texture, porosity, strength, dimensions, and texture.

Clay brick’s particular hue comes from the intrinsic color of the clay, while concrete bricks require a colorant to overcome Portland gray, making it less colorfast. While visually similar, they behave very differently in the wall and should not be combined. Clay bricks are porous and expand with moisture, requiring expansion joints. In a Comparison of the Behaviors of Clay and Concrete Masonry in Compression, R.H. Atkinson G.R. Kingsley writes, “Concrete bricks are impervious and shrink over time, requiring control joints. While clay and concrete bricks behave similarly for engineering purposes,” they do not for architectural purposes and should not be combined. Brick strength varies depending on its material and the method of production, ranging from minimum 1800 PSI to 5000 PSI. Existing brick strength should be tested to determine the strength of the mortar to be used, so that the mortar is always softer than the brick.

A range of sizes are standardized for modern brick. Bricks also have what are known as “specials,” bricks that have a particular feature, such as a bullnose corner (or two), a curved face, or a chamfer. These are all fabricated to perform a particular function on the building, such as for a water course, a sill, or coping.

Brick matches can sometimes be obtained from modern manufacturers, but frequently the best match is a salvaged unit. For dimensions, it is most important to match the height of the brick, while the length of the brick can be made up with the vertical mortar joints. When performing a renovation that removes any quantities of brick, the units should be salvaged for reuse in later repairs for the greatest success. This is especially true for bricks containing iron spots.

The texture of a brick provides visual interest and affects the reflectivity of the unit in the sun. If not matched correctly, the new unit will be obviously different in certain light, even if all other factors are matched. Some bricks are glazed, which makes them less pervious but provides a weathering face that is very durable. These bricks need to be matched for color of the substrate, the color of the glaze, and the gloss of the finish.

Deterioration

Bricks are a very durable material that can last indefinitely when properly designed and maintained. The mortar that combines the bricks is less durable by design, in order to protect the bricks. The mortar, when properly installed, should last 50 years, when the wall is not otherwise subjected to deteriorating conditions.

There are a variety of failure types for masonry. These symptoms should be surveyed and recorded onto drawings, so that patterns and correlations can be made. This mapping gives clues to the causes, such as adjacency to windows, presence of steel lintels, gutters, and downspouts, or adjacent features such as salted sidewalks. Typically, each failure has a cause that must be eliminated prior to the repair of the symptomatic failure, to affect a permanent repair.

Efflorescence is the deposition of salts on the surface of the brick, appearing as white staining. It is caused by moisture in the wall from broken downspouts, failing roofs, or failed window seals, which introduce moisture into the wall. This can be remedied by cleaning, as described below.

Cracking can be caused by one or more of several causes: a lack of movement joints, differential movement of the structure, or a design flaw of the support of the brick. Cracking appears as a fissure in the mortar, which can travel in a pattern indicating the stress in the brick. In extreme cases, the crack will extend through the brick itself.

Spalling can occur due to freeze/thaw cycles. If the wall can’t dry out, the trapped moisture freezes, expands within the pores of the brick, and causes the brick to fracture, typically at the face.

Bulging of the entire brick wall can occur when the wall has not been tied back to the structure. Moisture can get behind the front wythe of brick, expand, and push the brick out of plane, if not reinforced with row lock headers (or modern steel reinforcing).

Repairs

Repointing is the removal and reinstallation of mortar into the joint. (Please see the April 2019 Traditional Building article on mortars.)

Once the masonry has dried out over a summer season, efflorescence can be removed with mild chemical cleaners. This process starts with cleaning trials in a discrete location, trying solutions of the proposed cleaners to determine the lowest strength that is still effective. Work would begin with wetting the entire wall, applying cleaning solution with soft bristle brushes from the top down, then rinsing thoroughly. The wall should be tested with a pH strip to ensure that the wall has returned to a neutral pH.

To remedy the cracking, first understand and eliminate the cause. If differential movement of the structure is the cause, then the structural repairs should be effected before addressing the cracking. If the cracking is due to a design flaw, such as too great a span, too small a support angle, or where modifications have removed the support, then repairs should stabilize the structure to support the brick properly before repointing joints. If cracking is due to the building making its own movement joints, continuous expansion joints should be established in those locations. The expansion joint should receive sealant, while the rest of the cracked joints should be repointed. If any of the above causes has resulted in broken bricks, replacement bricks can be toothed in to return the integrity of the brick

When bricks spall, they are not repairable. Once the cause of the saturation is removed, replace the bricks in kind, using a full bed of matching mortar.

Where walls are bulging, they need to be stabilized. Once the cause of the bulge is removed, the one wythe can be disassembled and rebuilt. In some cases, where multiple wythes need to be tied back to the structure, there are helical anchors and other ways to stabilize the wall in its deformed state, but these require engineering.

With proper maintenance of all building systems, brick masonry will endure for generations. The greatest threat to it is uncontrolled moisture, which can be prevented by good maintenance of roofing, gutters, downspouts, window seals, and grade-level drainage.

Glazed Brick

- Like other brick, glazed brick is made from clay or concrete. Originally, brick was “salt fired,” where the kiln temperature was reduced, and salt (NaCl) was poured into the ports near the fire, which vaporized it, chemically mixing with the silicates in the brick to form a glazed finish.

- The color mostly comes from the color of the brick substrate and didn’t achieve the wide variety of hues available today. The process was not environmentally friendly and was replaced with an applied glaze.

- There are two methods for glazing brick, depending on the glaze. Some glazes can be applied to unfired bricks that are then fired at the typical high temperatures. Other glazes, which require lower temperatures for color consistency, are applied to fired bricks, and then re-fired.

- The glaze on a brick provides a design opportunity, as well as an impermeable surface which resists the accumulation of dirt and can be cleaned of graffiti. The same glazed surface also prevents clay brick’s natural drying process. As a result, the adjacent mortar must be as permeable as possible, to permit drying. If glazed bricks can’t dry out, the area immediately behind the glaze has typically the highest moisture, which can freeze, and cause spalling to the face of the brick.

- Bricks can be glazed in any number of colors. Further, the glaze can be applied to more than one face, for special shaped bricks. Glazed bricks can be interspersed with unglazed bricks, as long as all the bricks in the wall are made of either clay or concrete, but not both.

Susan D. Turner is a Canadian architect specializing in historic preservation of national registered buildings. She is the Senior Technical Architect for JLK, a woman-owned business specializing in the repair and preservation of historic buildings. She can be reached at sturner@jlkarch.com

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.