Carroll William Westfall

Urbanism and Happiness

Our understanding of happiness goes back to the ideas of the ancient Greeks, the same people who gave us the architecture that still occupies a fundamental position in our traditional architecture. There is, then, no wonder that their ideas and ours about happiness and architecture have deep connections.

So what is happiness? Here is a quick definition. Happiness is the fulfillment of our human nature. The ancient Greeks laid the groundwork for that definition, and they recognized that it is not a gift of the gods but attained through our exertions. They organized the work it required into three categories and defined an ideal for each: We act to achieve justice and the good; we observe and dispute to know what is true; and we make things to embody the beautiful.

Individuals do these activities, and so do communities, which are essential in assisting individual efforts. They found these ideals in nature where they believed that the gods active, and they identified nature with the cosmos that provided the best models for them to imitate when acting, seeking to knowing, and making.

To gain knowledge of the ideals, they engaged in never ending reasoned debates about what they observed the gods were doing and the changes they observed in the cosmos. Their efforts concentrated on separating the chaotic and unpredictable from the orderly and enduring to discern nature’s unchanging principles that would guide them as they imitated the ideals in their own acts, in their quest for truth, and in their making of things. They recognized that they could achieve these ideals only imperfectly, but in the striving, they could find the happiness that is allotted to them.

Their understanding of nature is ours as well, with the only important differences in the career of the discussion across the millennia concerning the actors in nature. Pagan gods? A Christian God? Some other divinity? No god at all but simply the inner workings of nature itself? To their credit the Founders in Philadelphia made a civil order based on imitating nature that left belief in the actors in nature up to each individual and used the force of government to protect each individual’s right to that belief.

Maintained all through the changes over the millennia has been the tenet that the ideals of the good, the true, and the beautiful enjoy an essential unity residing in an inner core within nature. This tenet also holds that in the lives of individuals and in their communities, each of these ideals plays its way out in acting, in knowing, and in making, and that in doing so it carries along that essential unity.

Misunderstanding the relationship between the entity on the surface and the unity in the core has led to all kinds of mischief. If they share a unity is goodness truth? Is truth beautiful? Is beauty good? Can evil or falsity be beautiful? Fallacy rather than insight can result if care is not exercised here.

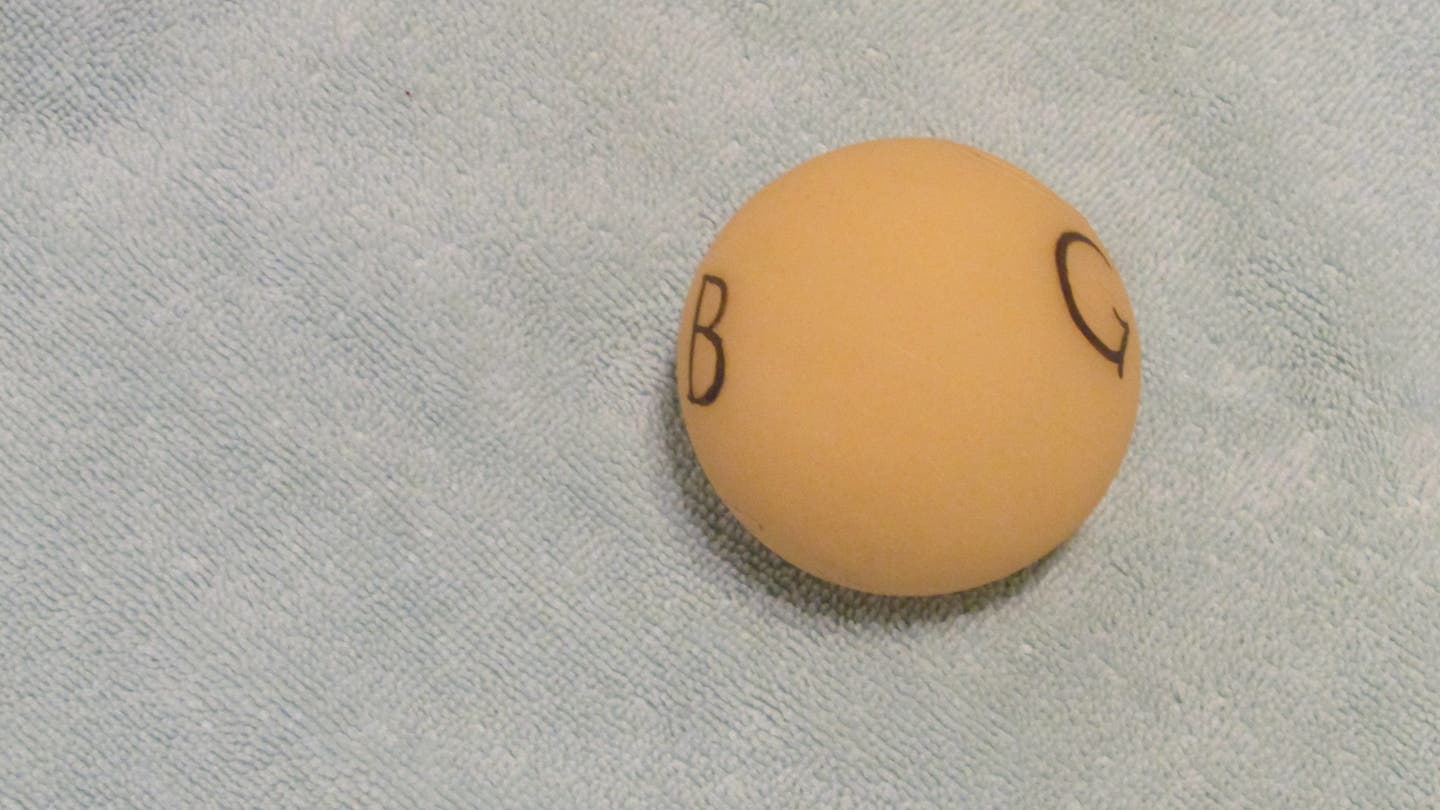

An image might help to get it right. Picture a ball with a G, a T, and a B equally separated on its surface. If our question concerns beauty, we can look at the B knowing that beneath it is the inner essence of the G and the T but they in themselves remain invisible. We know they are elsewhere on the surface, and moving the ball will reveal one or the other, but then the B is lost to sight.

Still, with that unity deep within, if our imitation of B is well made some essential part of G and T will also be present. But note: our judgment about the fullness of B’s ideal will not affected in their absence from our view of B. Now, in the best of all possible worlds when B is fully realized it will carry G and T with it, a condition only found in nature but itself an ideal for B, G, and T. In our mortal life, we have to accept G and T as counterparts of B, not as partners.

How are we to penetrate below the surface to knowledge of the ideals that guide our activities? Again, the Greeks worked this out in a way that has proven fruitful ever since. They offered an image of the great chain of all things in nature with humankind placed between the brutes and the gods. We share with brutes the capacity of utterance such as the howls of wolves and the clucks of chickens, and with the gods (or nature or God according to one’s belief), we share reason, which allows utterance to become speech.

The capacity to engage with others in reasoned speech is a capacity that is a unique endowment of humankind, and with it they discern they principles that give order to what they observe in nature, and in their own human nature, and in what they inherit from their predecessors. Using these principles enables them when acting, when seeking truth, and when making to imitate the ideals in nature that can fulfill their own nature and enjoy the profound and blessed happiness of their soul’s union with that of nature.

To attain happiness requires working with others in a community, knowing what predecessors have discovered, adapting it to new circumstances, and incorporating new knowledge. Such a community is composed of individuals bound by a common respected, even hallowed, tradition.

The largest community of this sort is a nation, which holds many smaller ones including the most fundamental, the family. Each of these uses its gifts and talents to draw on tradition as it builds a place to facilitate its pursuit. What each one builds will be both unique and a participant in the unity that nature harbors in its core. Visible to all will be the beautiful in the buildings and urbanism that facilitates the aspirations of one and all to live nobly and well and enjoy the fullness of their happiness.

In the subsequent opinion, I will cover the good and the true and then conclude with the beautiful and the sublime.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.