Carroll William Westfall

The Propylaeon

In honor of Mark Schimmenti, my boon companion for two summers in Pompeii as part of John Dobbins’s Pompeii Forum Project at the University of Virginia.

The temple front and the propylaeon are two distinctive compositional motifs that allow a building to stand out among other buildings. A temple is instantly recognized as iconic even today when reduced to a pedimented columnar front. When the temple was merged with a basilica, it became a church. Miniaturized, its front became an aedicule. And further reduced it decorates and enriches a door or a window with a frame.

The temple separates the best from the rest, while the propylaeon separates the better from the others with a row of columns. It might stand alone and even carry a pediment when serving as a gate separating one place from another, or be attached to a façade that separates inside from outside, staking a claim for importance among other buildings.

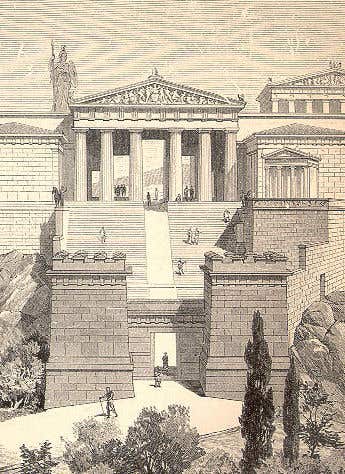

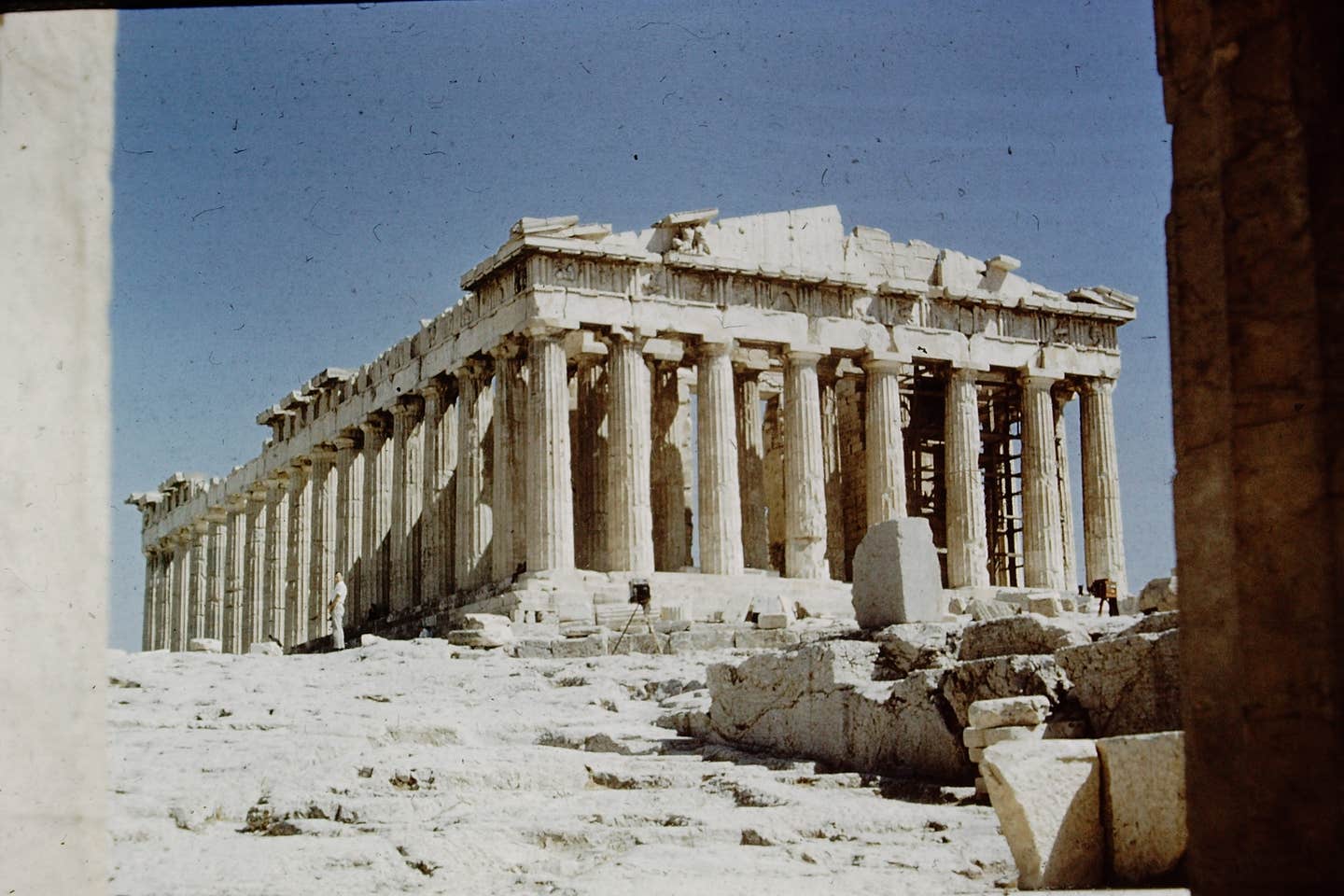

(1-3) The most famous propylaeon provides entry from the city where the Athenian mortals lived and into the high city or acropolis, the walled precinct built as a home for the gods whose favor they sought. Six Doric columns beneath a pediment were flanked on each side by an outbuilding facing west with a central aisle leading into the sacred precinct. Dead ahead was the large statue of Athena Promachos whose spearpoint provided seafarers with a navigation point. Passing through the four bays of the Propylaeon’s aisle and into the pedimented exit porch, off to the left the Erechtheum, a shrine honoring the gifts of the gods, is fully visible. The Doric Parthenon is off to the right rising above the ground’s slope. In our image we see it framed by the Propylaeon’s columns. Facing us is the chamber holding the treasury of the Delian League with its other, east front open to the statue of Athena. Upon entering the acropolis, we see the two great structures obliquely, which reveals the massing holding the Erechtheum’s three major elements and presents the Doric Parthenon in a view revealing it as a totality, an analogy to the comprehensive view available to the officials presiding over a public assembly of those responsible for formulating policies affecting all the Athenians. The worshipful processions entering the acropolis proceeded past the east-facing Ionic front of the Erechtheum and on to the Parthenon’s front facing east to welcome the gods’ visits to this sacred precinct.

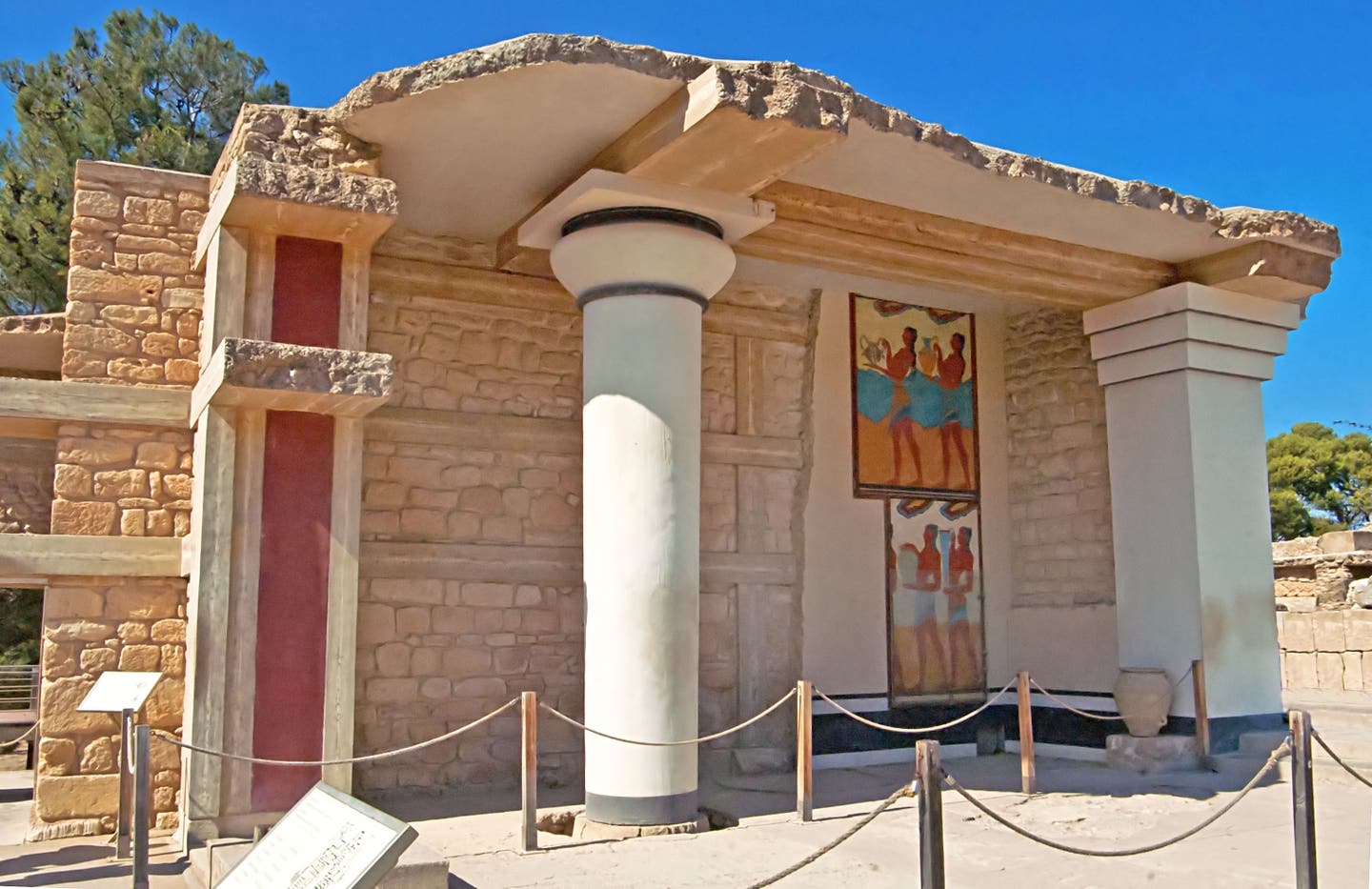

(4) A much simpler propylaeon provided entry to a special precinct in Pompeii, built sometime in the middle years of the 1st c. BC when the Samnites were adjusting to having fallen under Riman rule. It was sited to signal the presence of the triangular forum, an older site on a promontory sacred to the gods, and to the neighboring, newly built cultural district with a pair of theaters and other facilities for public use and entertainment. Its six fluted Ionic columns with no pediment was set back from the long, principal street running from the Porta Marina, across the end of the principal forum with the secular offices, and eventually reaching the amphitheater, beckoning visitors who espied it up a short side street.

(5) The Brandenburg Gate in Berlin is perhaps the most familiar propylaeon. Carl Langhans, court architect, built it in 1788-91 with its principal face inside the city’s custom walls that served as a gate separating two entities. Flanking it on it inner side is a pair of four-column temple-like custom houses with columnar stoas on their outer side. The central section’s five bays, the central one slightly wider and reserved for the king, are fronted by eight Doric columns with bases supporting an entablature and with a Victory statue on top. Lacking a pediment, otherwise it resembles a contemporary reconstruction of the Athenian Propylaeon when Germany was immersing itself in things ancient Greek.

The gate provided King Federick William II of Prussia access to his Brandenberg provinces beyond the hunting preserve, today’s Tiergarten, the more familiar side for views today. Our image shows its outer face in West Berlin on a dreary day in December 1961, four months after the infamous Wall was built.

In 1893 a quarter of the people in America made their way to Chicago to gape in wonder at the display of ancient architecture revised to serve the country’s achievements in the four hundred years since Columbus’s discovery. The World’s Columbian Exposition’s display jolted Americans to recognize the order and splendor that classical architecture and urbanism offered through thoughtful civic design, and hamlets and cities began their transformation supported by the era’s massive social and economic changes.

When basking in the well-earned accolades coming from the Fair’s success, its chief designer, Charles Follen McKim was commissioned by Columbia University to design a new campus on the largely barren northern Morningside Heights of Manhattan. Seth Low, a consummate New Yorker and President of Columbia from1890 to 1901 when he became New York City Mayor, selected McKim because he wanted an urban campus open to the city rather than the latest mode exemplified by the cloistered Gothicism that Henry Ives Cobb had begun 1891 for the University of Chicago a few blocks from the Fair.

(6) In 1896 Columbia moved into McKim, Mead, and White’s campus that adapted the precedents of Thomas Jefferson’s rural University of Virginia and the Fair’s exuberant urbanism. Its limestone signaled the classical, its red “Harvard brick” referred to America’s earlier classicism, with propylaea, absent from dormitories and general use buildings but present for others, providing a graded hierarchy. (6) The centerpiece is the limestone Low Library based on the Roman Pantheon but with a propylaeon of twelve fluted Ionic columns and no pediment rather than a temple front. (7) Near it is the Saint Paul’s Chapel designed by Howells & Stokes added in 1903-07. (8) And next over is Avery Hall occupied since 1912 with its four fluted Ionic columns standing free before the central entrance, built to house the premier architecture library with the facilities for Columbia’s architecture school above.

(9) The year the campus was designed, Holabird and Roche designed another of the new Chicago Commercial buildings that had been impressing the Fair’s visitors. The most rigorously classical among these early steel-framed Chicago School buildings at 16 stories is composed column-like with a base, shaft, and capital. The base has shops open to the street, and the next floor with a greater height had the prestigious banking floor. Next up, the column shaft rises as piers between broad bays filled with “Chicago windows,” culminating in the two top stories that suggest an architrave and high frieze crowned by a generous overhanging cornice. On the two street facades the outermost bays are framed with deep drafting and surface texture suggesting rustication to complete the suggestion that this is modern successor of an Italian Renaissance palace.

(10) A propylaeon attached as the entrance elevated the status of this building, an investment by Boston developers, above its peers. Its three polished Ionic columns stood between deeply drafted piers with reentrant pilasters that carried an entablature that broke out from the façade. (11) Behind the columns after a brief gap, polished marble pilasters and bronze reliefs above the four portals (surviving to decorate the building’s entrance) led into the double-height elevator lobby with Tiffany mosaics that, like the portals’ bronze panels, celebrate the 1673 transit of Marquette and Joliette through the site that would become Chicago’s.

The propylaeon’s columns, piers, and entablature are long gone, perhaps since 1950 when subway construction necessitated rebuilding front wall’s foundations or earlier, after a 1912 ordinance was enforced to purge the city sidewalks of obstacles. A sixth bay was added on its narrow side in 1904 distorting the building’s cubic massing, and in about 1950 the cornice was removed. A multi-year restoration began in 2001 has replaced it, a century of soot that blacked the building was scrubbed off to retore the red terra cotta façade, and the lobby was rejuvenated.

(12) The Marquette’s prestige was challenged when a pair of buildings used temple fronts to raise the ante. The Continental Illinois National Bank (D.H. Burnham, 1911-14) and the Federal Reserve Bank (Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White, 1919-22) were built with attached temple fronts facing one another, Ionic for the former, Corinthian for the latter, at the foot of LaSalle Street. When the Chicago Board of Trade Building at the street’s termination was replaced by its even taller replacement (Holbird and Root, 1925-30), style had drifted into the new streamlined “Art Deco” style, the third of the white clad buildings that completed one of America’s great urban ensembles.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.