Clem Labine

The Hidden Costs of ‘Starchitecture’

It’s obvious that trustees of most museums and other cultural institutions are bedazzled by the idea of "starchitecture." When commissioning new buildings, they don’t merely want a structure to house the functions of their institutions. Their primary desire is for a sculptural edifice that will attract acclaim from architecture critics and "buzz" in the popular press.

What these institutional trustees don’t realize is that many of these “cutting edge” buildings by brand-name architects come with major unanticipated costs. The latest example is in Denver, where Daniel Libeskind’s radically designed new pavilion for the Denver Art Museum is undergoing a major re-roofing because of leaks it’s had ever since it opened in 2006. The building’s official construction cost was $110 million – but that doesn’t include the price of replacing much of the leaky roof. No one is saying how much the massive roof repairs will cost – nor who is going to pay for them.

Another well-publicized example is the lawsuit MIT filed against architect Frank Gehry and the building contractor for MIT’s new Stata Center, which is full of dizzying angles. The suit alleges that deficient design services and drawings caused leaks to spring, masonry to crack, mold to grow, drainage to back up and falling ice and debris to block emergency exits.

And at Harvard, modernist Otto Hall, opened just 19 years ago, is slated for demolition because its exterior walls have deteriorated so badly that Harvard says it’s cheaper to tear it down and start over.

Leaning towards the absurd

The question here is not who is going to pay to correct these building defects? Rather, the real question is: Why is anyone surprised these buildings have problems? Institutional clients have set themselves up to incur these extra costs by becoming mesmerized by what former Boston University president John Silber has called “the architecture of the absurd.” Problems with radically designed “absurd” buildings are common enough that it has given rise to the aphorism: “All prize-awarded buildings have multiple defects.” Yet despite this track record, clients profess to be shocked and irate when their “cutting edge” buildings require extensive, expensive repairs.

Advocates of traditional architecture have always pointed out that traditional design is more likely to produce successful outcomes because it is based on generations of experience about what actually works. The more iconoclastic a design becomes, the more the architect has to invent untested building details. As the designer piles on convoluted geometry, new materials of construction, innovative mechanical systems, custom-fabricated components, etc., the chances of unanticipated consequences increase exponentially.

Paradoxically, computer design seems to have compounded the problem. Sophisticated software now gives architects the confidence they can design anything. A building with convoluted twists, turns and angles works just fine inside a computer. However, it doesn’t rain inside computers.

The moral for institutional clients is clear: If you want your starchitect to produce a never-seen-before extreme design, just make sure your trustees and donors have extra-deep pockets. Because you’ll have to pay to erect the building – and then pay to fix it afterwards.

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.

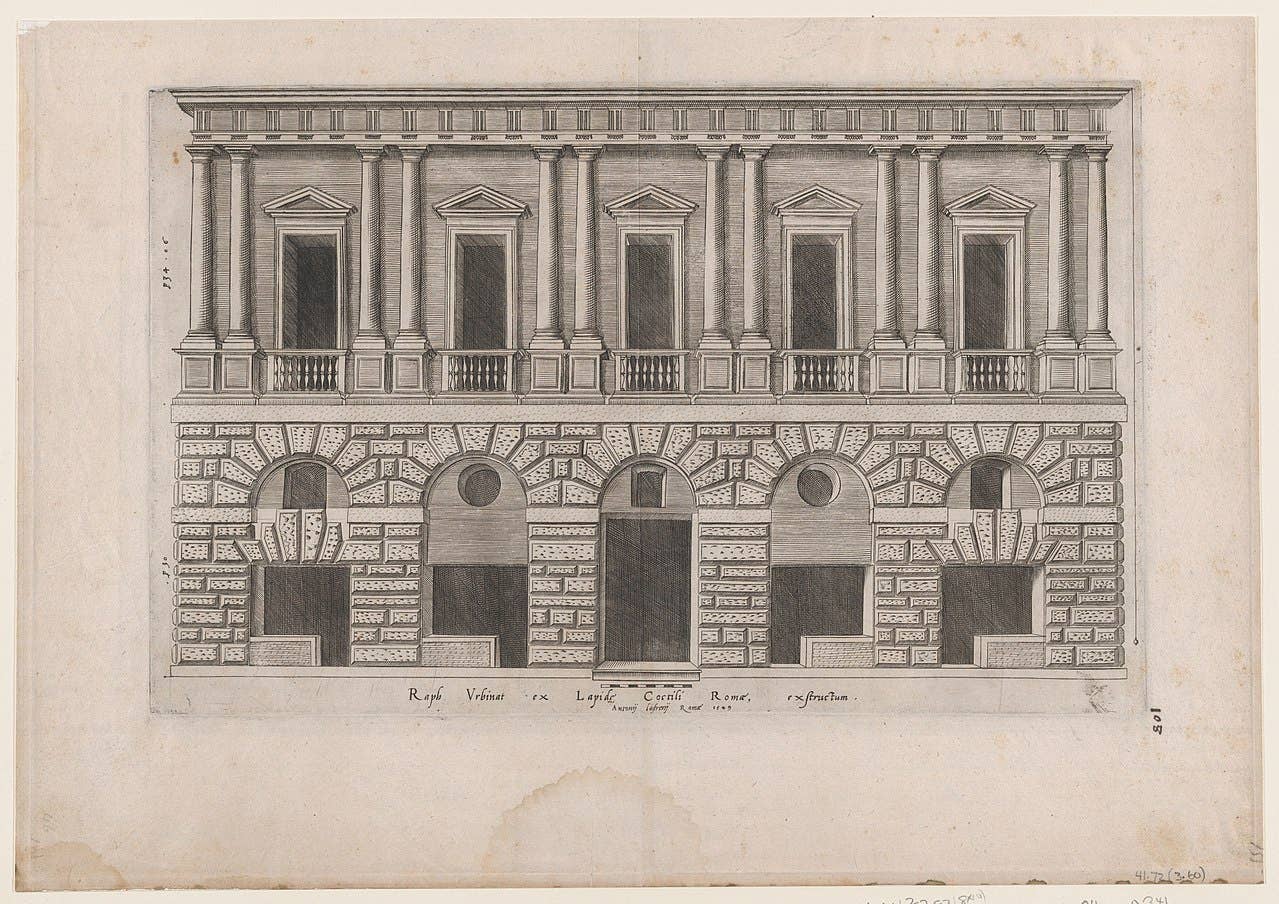

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.