Clem Labine

Teaching Architectural Design a New Way

A radical new full-year, full-time program for teaching young architects unique design skills is now underway in New York City, sponsored by the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA). This revolutionary school is called The Beaux-Arts Atelier and has already attracted the attention of national media like The Wall Street Journal. The fundamental goal of the curriculum is to develop an architect’s artistic sense and appreciation for beauty of form, while at the same time teaching a systematic design method.

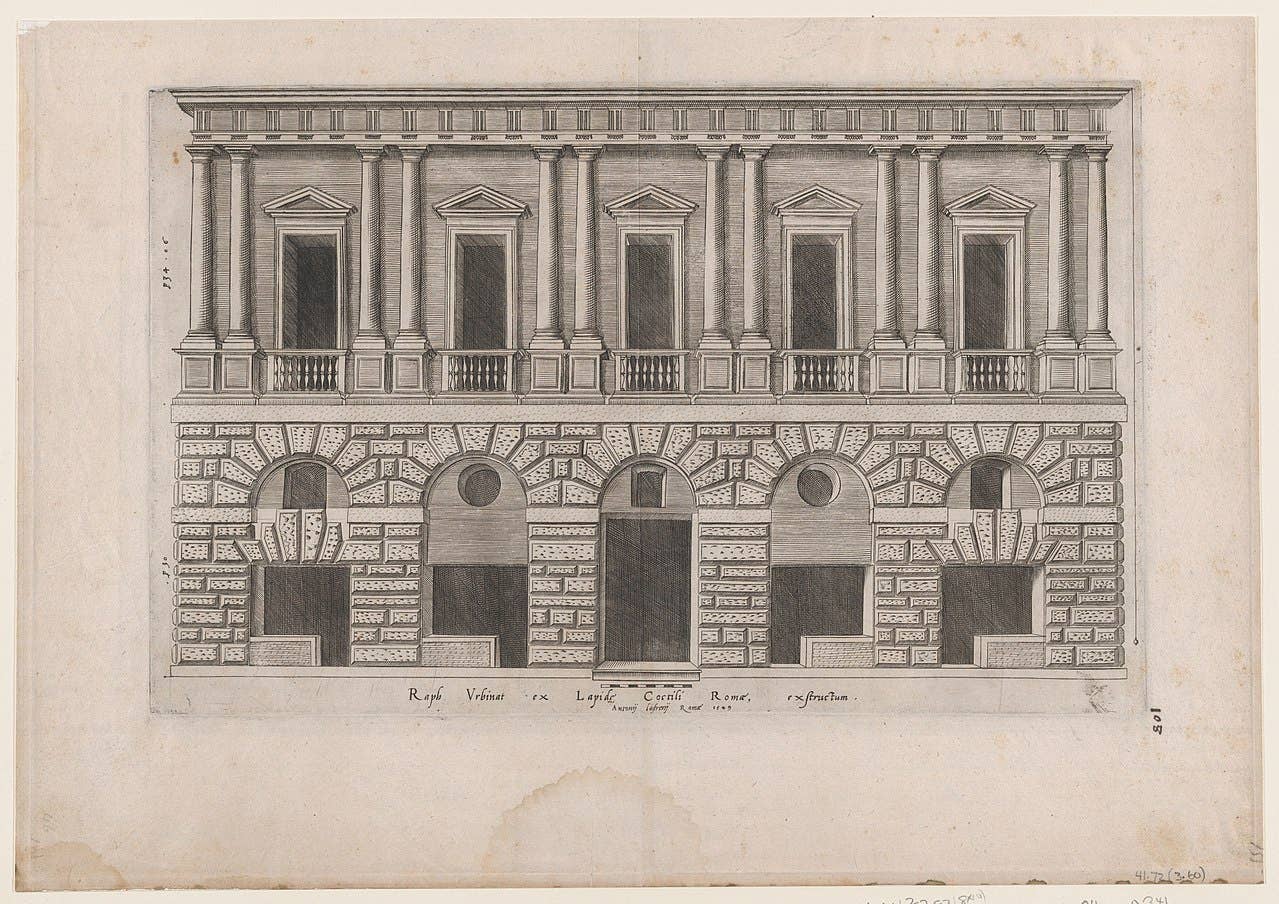

Ironically, the unique instruction system being deployed in the Atelier would have seemed quite conventional to architectural students a hundred years ago. The Atelier is based largely around teaching methods developed originally at the world-famous L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris – where many giants of American architecture were educated. By the early 20th century, most American architecture schools were using many of the Beaux-Arts teaching methods – as set forth in John F. Harbeson’s pioneering book, The Study of Architecture. However, the Beaux-Arts system was ejected from architectural courses after World War II when Modernist faculties took control of the academies – and Harbeson’s book ended up in trash bins. (Happily, Harbeson’s book has been reprinted.)

The Curriculum

Beaux-Arts teaching is built around manual skills – especially drawing and sketching – so that the hand can educate the brain. In the age of AutoCAD, many young architects don’t learn how to draw; as a result, an ability to relate to the natural world is lost. There are no straight lines in nature, and the capacity to capture subtle curves and the interplay of light and shadow learned through hand drawing enhances the ability to design beautiful structures. That’s why you’ll find no computers in the Beaux-Arts Atelier – and why the curriculum includes such classes as figure drawing, hand-drafting, modeling and sculpting, the classical orders, proportion and geometry and architectural rendering.

All the newly heightened aesthetic skills come together in the Design Studio, where students are taught a systematic design method that lies at the core of the curriculum. To start off this year’s Design Studio, students were sent off to New York’s Bryant Park to take careful measurements of a small pavilion by Carrere & Hastings that is part of the 1911 New York Public Library complex. After making drawings based on their measurements, the students are challenged to analyze the components of the design and then to use those concepts as the basis for a large urban gateway. The idea is to guide students slowly through successive design problems – and to systematically teach something new at each step in the process.

To keep the intimate atelier atmosphere, the program is limited to 12 students per year. Having 10 instructors for the students makes the Beaux-Arts Atelier quite a varied and rich educational experience. To cap off their academic year, students spend two weeks in Rome drawing and painting – and studying how Rome has successfully integrated new buildings into its historic context over the centuries.

The Beaux-Arts Atelier holds the promise of teaching a new generation how to appreciate and – more important – how to design beautiful structures that will contribute to a more humane built environment. Let’s hope its influence spreads.

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.