Carroll William Westfall

Statues in Urbanism, Again

The statues on Monument Avenue in Richmond have begun to fall. On July 1, a new state law allowed local authorities to begin a minimum 60-day process leading to their removal. Richmond’s Mayor, impatient to begin, invoked emergency powers to remove Stonewall Jackson that day with Admiral Maury and two cannons marking the city’s defense line the next day. Court injunctions are protecting Robert E. Lee, the largest and most prominent, and Charlottesville’s two equestrian generals that sparked fatal demonstrations in 2017. J.E.B. Stuart may be in exiled from Richmond by the time you read this.

Monument Avenue’s meaning was been under review well before that fatal day in nearby Charlottesville, and ever since there have been various suggestions for giving it new meaning. Other cities feeling the rage of the Black Lives Matter movement in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic have had to address the statuary in their urbanism, but Richmond’s prominent in events leading to what is being protested gives national import to what happens locally. They celebrate Richmond, the Capital of the Confederacy, as the capital Lost Cause renunciation of Reconstruction and its companion, Jim Crow.

Richmond has older statues. The Virginian George Washington took his place in 1796 in Jean-Antoine Houdon’s marble statue in Thomas Jefferson’s State Capitol. On the Capitol Grounds Jefferson and five other, Virginians surround the tall equestrian statue of Washington (1850-58; the others by 1869; Thomas Crawford and Randolph Rogers), and Jefferson is in the glazed atrium of the luxury Hotel Jefferson opened in 1895 (Edward V. Valentine).

After Hollywood cemetery began receiving Confederate dead, Charles H. Dimmock in 1868-69 built a tall, steep pyramid. In 1875, the “Southern People” accepted from a group of Englishman a gift of a modest standing sculpture of General Stonewall Jackson, “soldier and patriot,” and placed it in the Capitol Square (subsequently relocated).

As veterans aged and Lost Cause sentiment deepened, Confederate monuments began proliferating in Richmond. In 1891, the native General A. P. Hill was placed above his tomb in a traffic circle. In the drill field that became Monroe Park, a monument to The Richmond Howitzers was placed in 1892, and in 1894, another to General Williams Carter Wickham, a local boy, both now toppled. Johnny Reb seems safe atop the tall column of the Confederate Soldier and Sailors Monument since 1894 but much longer?

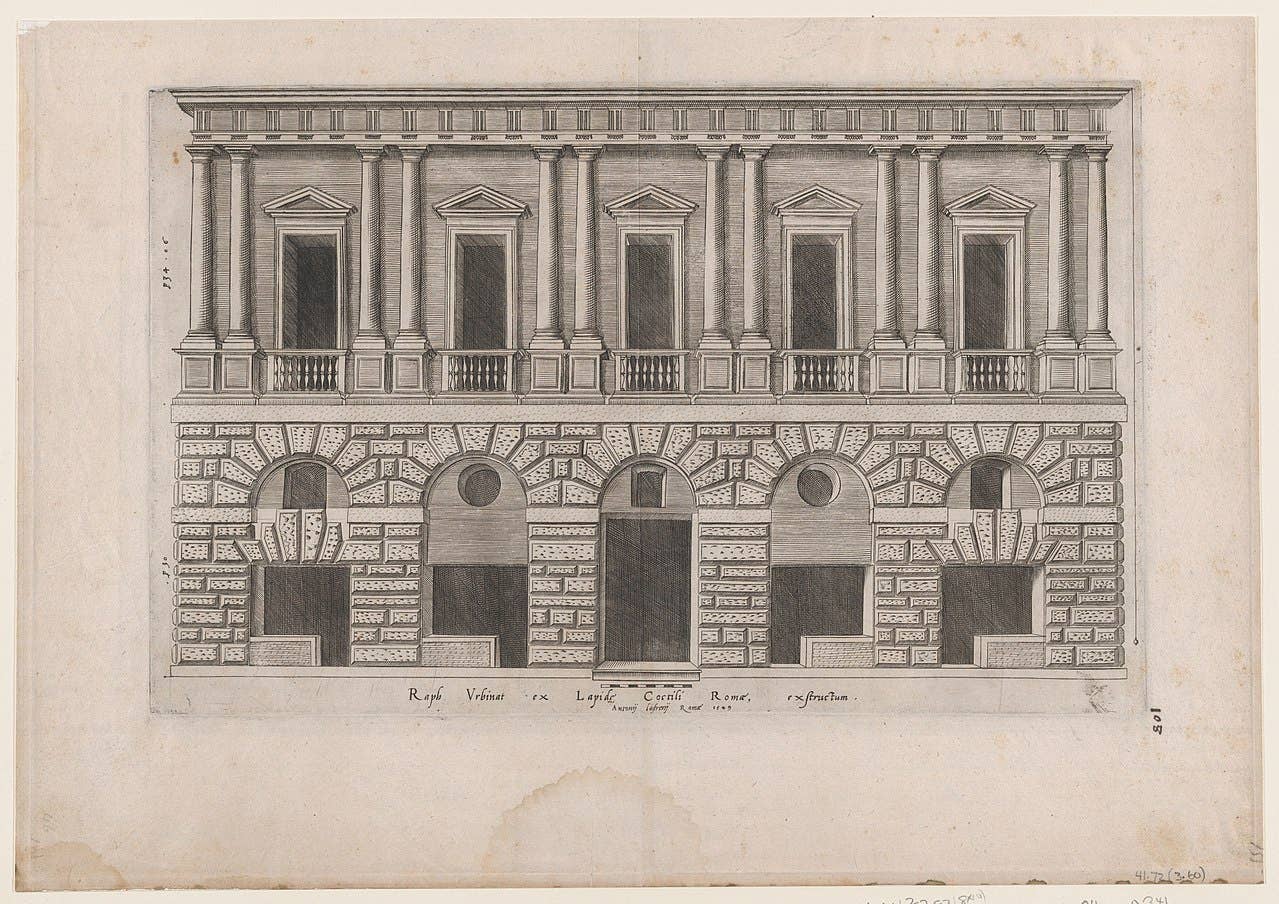

Things intensified when The Lee Monument Association got busy. In 1887, Colonel Otway C. Allen, son of a successful land developer, platted an eleven-acre development with a brief boulevard, Allen Street, and the broad Monument Avenue beginning at an area being filled in by solid citizens and extended over time with a fifty-foot turf and arboreal median to produce a posh neighborhood with smaller streets and lots behind. At their intersection, a 100-foot circle within a 200-foot circle was offered to the state and accepted by Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of Lee, a former General and now Governor. Maruis-Jean-Antonin Mercié was selected to sculpt the monument in Paris, and in 1890 it was unveiled on its monumental pedestal before a crowd of 100,000.

Next came Cavalry General J.E.B. Stuart (Frederick Moynihan) astride a spirited horse in a smaller circle at the Avenue’s head, and four blocks east of Lee was Jefferson Davis (also 1907; Edward V. Valentine, toppled; setting by W. C. Noland with Vindicatrix or more popularly Miss Confederacy atop a 60-foot column). Their dedications just four days apart attracted a procession of 1000 veterans and their sons and as many as 200,000 spectators. General Stonewall Jackson atop his horse (1919; F. William Sievers) got his due three blocks farther west, and two blocks farther and 1.2 miles from Stuart came Matthew Fontaine Maury, “pathfinder of the seas” (1929; Sievers).

Elsewhere in the city were Columbus (1927; thrown into a nearby lake) and a monument to the First Virginia Regiment (now the Virginia Defense Force; 1930) formed in 1754 and engaged in every war ever since was cast down because it had fought in the Civil War.

Richmond’s protesters have given the Avenue’s monuments the most extensive graffiti. While its present residents are like those who first lived there, in close proximity are university students and other young people. The city’s protesters, largely young and white and calling for what Reconstruction ought to have delivered, have made the Lee circle the center of their activities and renamed it Marcus-Davis Peters Circle, after an African American educator gunned down by a police officer in 2018. The early assemblies and processions sometimes spilled over into looting and burning nearby shops, and police, on cue, intervened with chemical weapons and arrests; the city now has its third police chief since late June.

More recently, a smaller and festive crowd in the evening offers hot dogs to visitors as they dance, sing, play basketball, and project images on the base Lee still occupies. Police occasionally carry off their equipment but provide information about where to retrieve it.

**************

Virginians gradually became less “Southern People.” In 1969, Douglas Wilder was elected to the Virginia Senate, the first African American since Reconstruction, and in 1986 in another first, he was elected governor. As Governor he secured a place far down Monument Avenue for a statue installed in 1996 of Arthur Ashe, a Richmond African American international tennis star and philanthropist encouraging reading. In 1973, another Richmond native, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson (Jack Witt, in aluminium), was installed in perpetual dance in the center of African American business and social activities. Nearby in 2017 Maggie Walker, an African American entrepreneur and philanthropic millionaire, was honored with a statue by Toby Mendez on the city’s principal street near her home. Last year a Native American and an African American were among seven of the intended ten statues for the Virginia Women’s Monument (Ivan Schwartz) in Capitol Square. The only nonfigurative work of any importance is a 27 foot spire with the text of the 1786 statue that Thomas Jefferson drafted at the First Freedom Center and Monument attached to a hotel opened in 2015.

Certainly other cities have important figurative, commemorative statues. As if tit-for-tat, an equestrian statue of Ulysses. S. Grant (Louis T. Rebisso) in Lincoln Park atop a high, arched triumphal base was unveiled before a crowd of, again, 200,000, in 1891. Lincoln Park already had a “Standing Lincoln” in 1887, and in 1908 Grant Park got the “Seated Lincoln” (both August Saint-Gaudens and settings by Stanford White). In 1956, Lincoln by Avard Fairbanks is in Lincoln Square, Chicago. Even Richmond has a Lincoln. Since 2003, he and his son Tad (David Frech) have been seated at the National Battlefield Park at Tredegar Iron Works where Confederate armament and materiel were manufactured to commemorate their visit to Richmond April 4 and 5, 1865.

The statues have their defenders. A lawsuit seeking to protect Lee cites, the original deed of gift that requires the state to keep the site “perpetually sacred” and “faithfully guard it and affectionately protect it.” If the statue goes, the Allan heirs would get the land back. The other suit contends that its removal would have “a substantial adverse impact” including “the loss of favorable tax treatment and reduction in property values.” Five plaintiffs, fearful for their and their family’s safety, remain anonymous. So far three judges have recused themselves without giving reasons and a fourth has done so to avoid an unspecified “conflict of interest.”

In anticipation of their removal, a lively local topic has been what next? Proposals fall into four categories. Replace them with new statues with suggestions including Sojourner Truth, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, Martin Luther King, Jr., W.E.B. DuBois, Blacks in their Union uniforms, and various local leaders. Another would have non-statuary art, such as fountains that are among Rome’s great attractions, or new uses such as playgrounds for children. A third would leave the pedestals empty and graffiti-covered: let the statues “just be gone.” Others would have the Lee circle remain a performance and gathering place where a local resident has given well-received recitals on her cello, images of admired individuals have been projected on the empty base; have this continue. And of course, there are those who would replace the Confederates with “public sculpture,” which is certainly the worst idea.

At present, this means works such as Alexander Calder’s Flamingo added to the Federal Plaza in Chicago in 1974 or the Bean (officially Cloud Gate) by Anish Kapoor in Chicago’s lakefront park since 2006. These offer enjoyment, fun, and diversion, which is fine, but they would hardly do the work that the Lost Cause partisans did, which was take a stand in the civil discourse that is the most important work of a city. Their stand was for an unjust a cause, and that is what the renewed stand must be about as we seek to right the wrongs of the past with a revised and revivified urbanism not just locally but nationally.

Urbanism serves civility, and civility serves and protects the right to pursue happiness, but there is no right to do a wrong, which those Confederates clearly and unambiguously sought to do. Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and other Virginians and Americans have been tarred with the same brush, but surely on balance their words and actions to promote the good outweigh their other actions, wrong as some of them were. Leave them alone.

But renew Monument Avenue to bring our understanding of the past up to date and address a future that will serve social, economic, and political justice.

We have the materials available to take that first step. Shortly before his recent death, Bill Royall and his wife Pam provided the money for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to acquire Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War (2019) after its debut in Times Square. In a conversation with the artist reported way back on December 21, 2019, the artist said he did not favor melting the monuments down but “creating more speech that allows the language of domination, of monumentality, to be recycled, towards the betterment of society.” Citing refutations of Holocaust deniers, he said “history is something that should be returned to, but also kept within the right context.” He explained that he made the rider on his mount explicitly African American and used the J.E.B. Stuart monument was the model for his sculpture.

The sculpture now occupies a pedestal at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts that in 1883 became Lee Camp Number One for indigent Confederate veterans. Elsewhere on the site but not visible from the new statue is the popular statue of a haggard Civil War Horse (1997) at Virginia Historical Society. Now that the law allows it, this statue ought to replace Lee a block from Stuart who ought to remain on his lesser base or, if removed, brought back. Over time the remaining vacant bases and new ones in new circles along the Avenue can be used to display new figures who have led us in our fight for social, economic, and racial justice.

Surely the conversation deciding who belongs there, if conducted with goodwill, could provide the community with a healing balm, which is one of the primary marks of civility and good urbanism.

A native of Richmond said it well. He never looked up at Lee but now as he drove past the graffiti and protesters he felt “empowered as a Black man on Monument Avenue, a thoroughfare anchored by tributes to people who fought for slavery, and lined by old-money homes.” As a first step toward an urbanism that serves all the people, we need to restore that street and every street in every city to make them routes that empower everyone to achieve the rewards that the few have kept from too many.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.