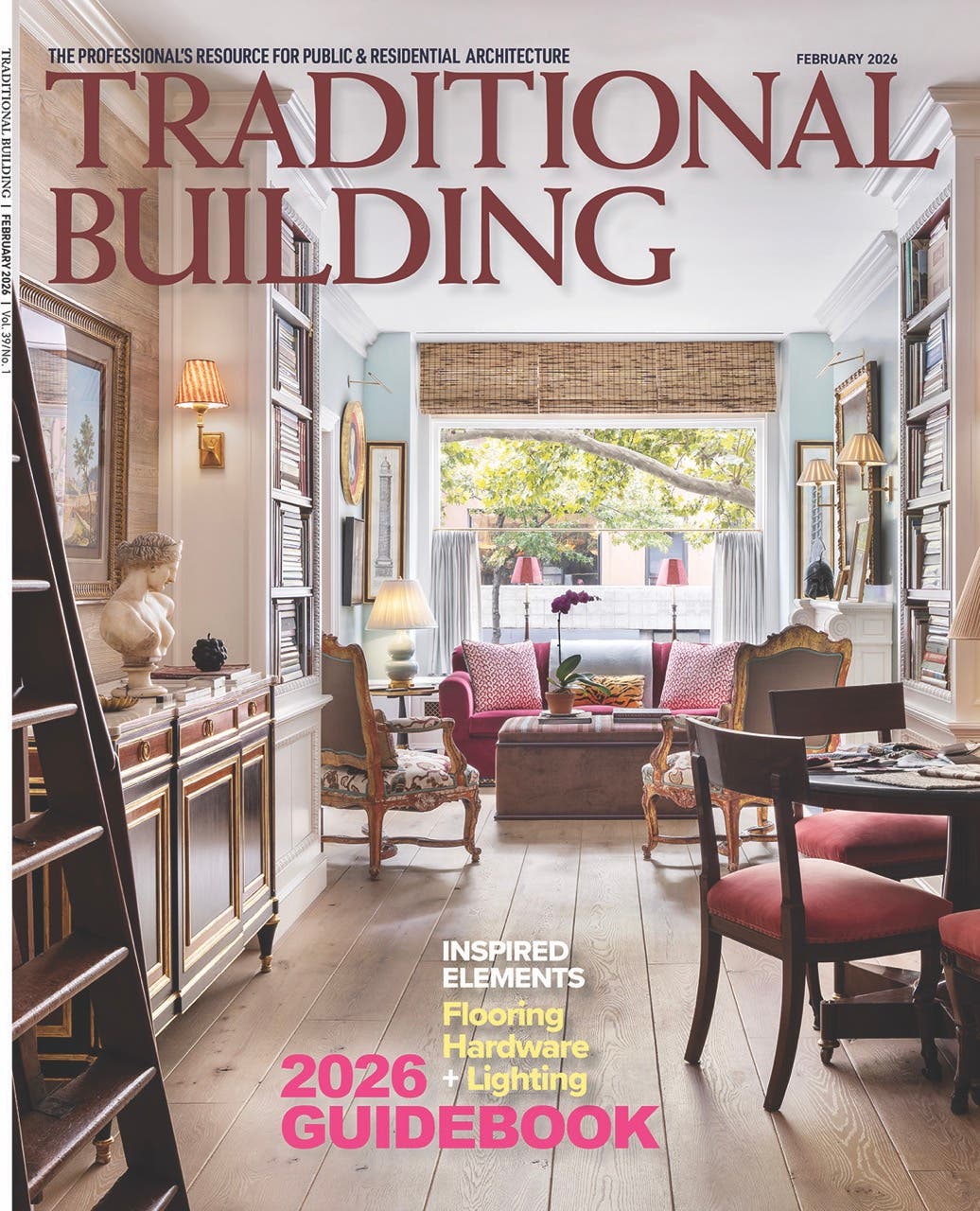

Carroll William Westfall

Right Sizing Commerce in Rome and Richmond

When I lived in Rome four decades ago the side of the Pantheon blocked most of my view from my apartment. The building’s other residents were equally low budget, but its piazza was ours. Today the building remains low budget, but most of the nearby buildings have moved upscale.

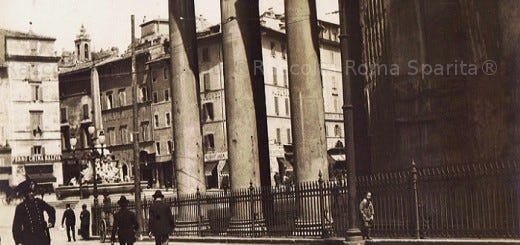

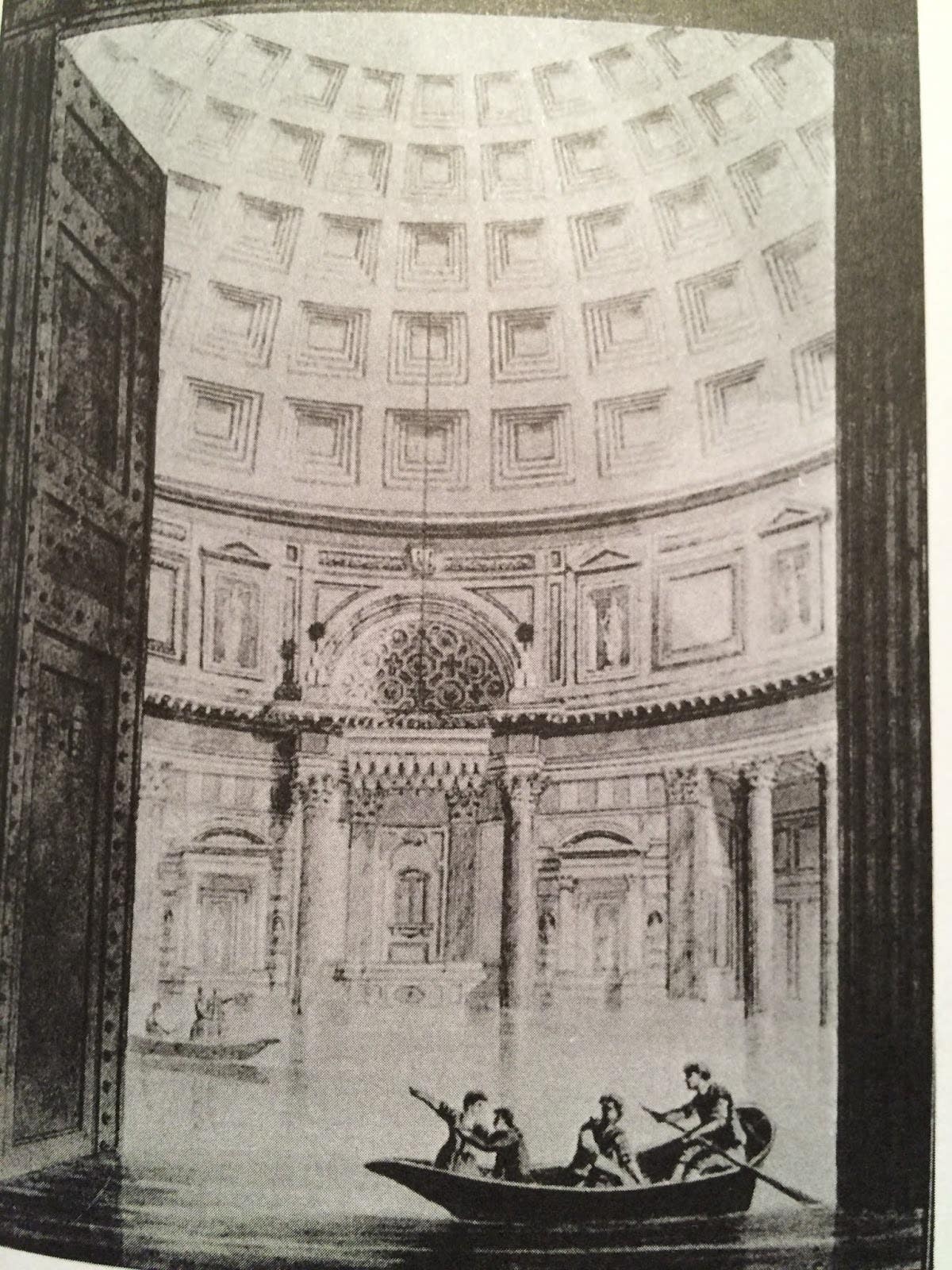

The Pantheon was built within a walled precinct above broad steps. Today we walk down across the piazza to enter it because for a thousand years uncollected garbage, collapsing buildings, and Tiber floods raised Rome’s ground level an estimated foot a century. Around 1450 the local government began paving streets and collecting and dumping waste in the Tiber, which stabilized street grades but exacerbated flooding; in the down-at-the-heels bar facing the Pantheon there was a photograph of people in a rowboat inside the Pantheon. [Figure 1, 2.]

Men waiting for a day’s labor hung out at that bar. As the days got shorter and colder they followed the narrow shaft of warming sun moving along the piazza’s edge.

The Pantheon was consecrated as the Christian church in 609, and remains one today. Its environs have always been lively with appendages holding shops and flats and even a butcher market under part of the portico. [Figures 3, 4, 5] Those are gone now. The capitals at the butcher-shop end are 17th-century replacements (the others, eroded originals remain), and a modern moat reveals the ancient grade. Since Rome’s 15th-century revival the district’s buildings facing the piazza and main streets have grown to four, five and six stories but still with residences above ground floor shops. As tourism and prosperity increased the down-at-the-heels bar became a McDonalds. Now, with more than six million tourists a year visiting the Pantheon, it is an upscale bar associated with the neighboring restaurant and tables, chairs and umbrellas in the piazza.

In the street leading toward the Pantheon’s rear is the Cartoleria Pantheon. Here architects equip themselves with sketchbooks, and others find beautiful papers and leather-bound notebooks probably not unlike the ones it has offered since it opened in 1910. The façade of its tall building has been repristinato but otherwise remains unchanged since who knows when. [Figure 6]

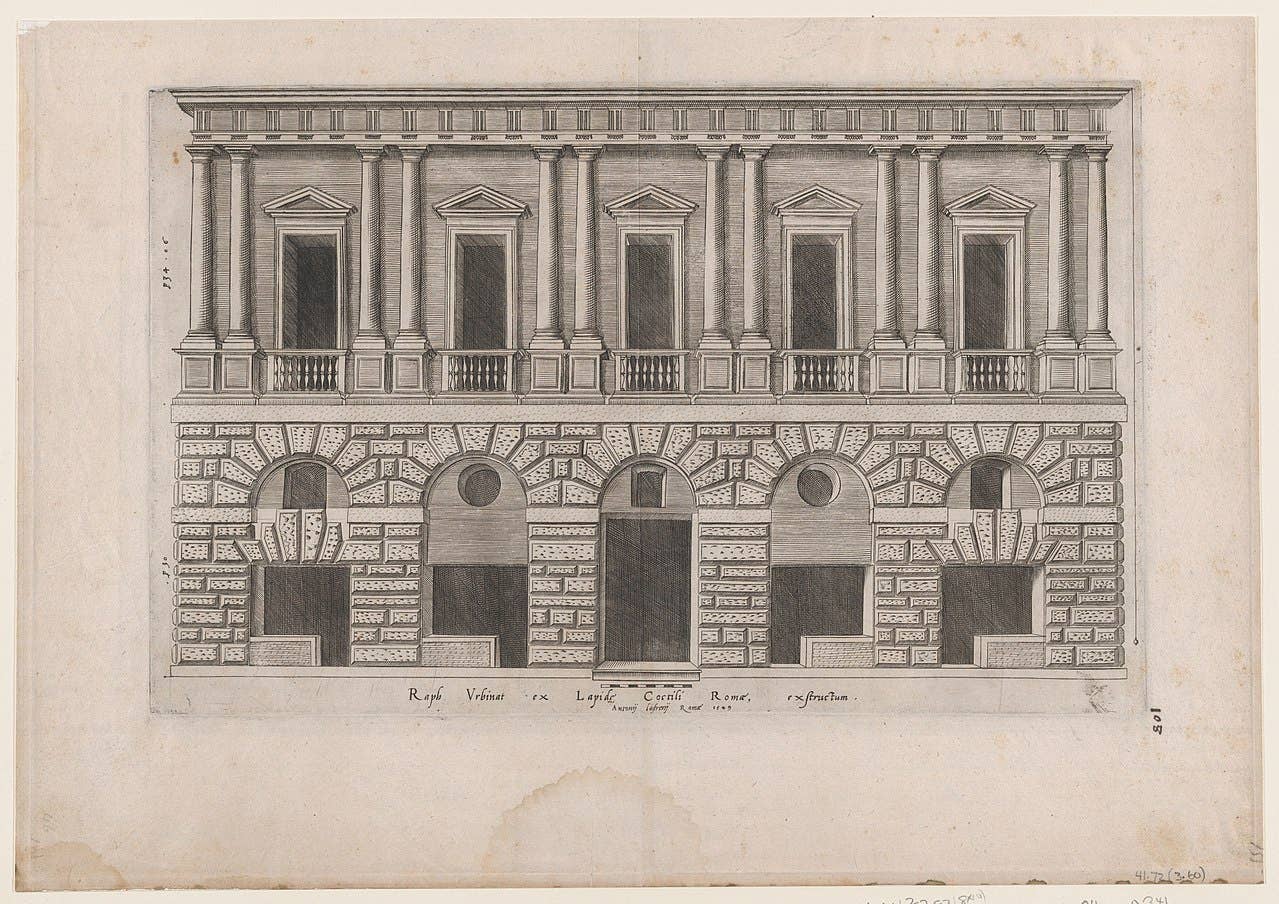

The same has been the case for nearly all of the buildings facing Rome’s streets and piazzas. Rome’s traditions of building and design have furnished the same parts and pieces for them and for the Pantheon and the other great monuments, but there is never any confusion about the relative importance of the buildings’ roles in the city. They all achieve firmitas, to use a Vitruvian term, but they differ in commodity, that is, their role in the civil life, and those roles are far from equal. The differences are clearly expressed in the size, scale, composition of massing and skins, materials, etc. To invoke another Vitruvian term, this allows their architecture to honor decorum, a quality that allows classical and traditional buildings to express the diverse roles they play in the city.

Commerce

Offering coffee and paper goods are important services, although both most likely arrived in the city well after the shops offering them were built. Even since 1910 commerce and urban populations have grown and rural populations have shrunk. In the last few decades commercial activity has claimed an increasing presence in cities leading many retail establishments to claim ever larger floor areas. Within a few hundred steps of the Pantheon supermarkets are offering goods along sometimes labyrinthine routes winding through the ground floor of contiguous buildings, leaving intact the older fabric that makes Rome an enduring, commodious, useful and beautiful city.

In Rome as in traditional, walkable cities ground floor commerce within the various neighborhoods enliven the interactions of citizens who come to know one another’s needs and interests. But a Venetian friend of mine dislikes Rome, as Venetians tend to do, not least because it let modern convenience undermined civility. He found their citizens to be cold and its local government unresponsive to the city’s needs. When going about their daily rounds they seal themselves away in busses, scooters, Fiats and Lancias that are constantly threatening those on foot. In his Venice (before the tourist inundation changed things) the small size and intimate scale of piazzette and vincoli with shops scattered along them allowed the pedestrians wearing fur coats and in workingmen’s cloth to interact and come to know one another’s needs and interests.

American cities used to be more like Rome and even Venice. They were built piecemeal, although more quickly and with smaller scale buildings until recently. When commerce gained dominance dense, specialized commercial districts developed in the transportation center with residential districts accessible on foot surrounding them. Large houses on large lots stood in front of narrow streets with row houses on small lots on narrow streets with the occasional corner two- or three-story flats-above-a-shop or strip of single story shops; many still thrive. [Figures 7, 8, 9]

When the nation’s first electric street car system began running in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888 the city’s development could jump the industrial land along the railroad hemming in the built up area and open the outskirts to “city additions” with small and large lots. These were sold individually with houses proportionate to the lots and built on across time (mine in 1937; in my block six others between 1918 and two in 1951, one of them a two-flat.)

A few streets had sidewalk-hugging strips of stores, but never enough or close enough. [Figures 10, 11] In them as in Rome, when the shop’s business changes so does its public face but the building’s fabric remains intact, its firmitas absorbing the changes that the new business demands. And they honor decorum (unless misguided remodeling makes alterations, often reversible). They become welcome members of their neighborhood by their proximity to residences and by following the residential styles but at a properly diluted level. Their neighbors are the individual residences where one or perhaps a few families live, and the residences occupy yards as do the churches, schools and neighborhood library, all scattered about and themselves dutifully honoring decorum. Parking? Many patrons walk to the shops, but others find convenient parking on the street or in a vacant lot across the street.

Every city has thrown-away districts whose roads host fast-food outlets wearing their own livery and coming and going with disturbing frequency. [Figure 12] Near them one often finds disused, low-slung century-old warehouses and factories now offering shelter to low-budget commercial activity. Gentrification is changing some areas, but others remain, displaying the failure of recent practices in urbanism and civility where minimal services are offered to the residents of their neighboring low-cost rental housing and public housing projects.

Meanwhile the more affluent flock to the other visible failure, the ever vaster and inhospitable suburban fringes and the urban routes leading out to them. Among their many faults is their failure to insert vernacular commerce into habitable, walkable neighborhoods. Rome does so, and so did Richmond and every other city in between, each in its own way. Instead those in charge of rehabilitating and expanding our cities treat urbanism as a service to developers’ and builders’ bottom lines and sources of (always inadequate) tax revenue, forgetting that they ought to be building areas where urbanism assures that commerce serves the civil life of their citizens. A healthy, civil society needs diversity of every sort but recent default practices merely amplify isolation.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.