Carroll William Westfall

Incremental Change and Tradition

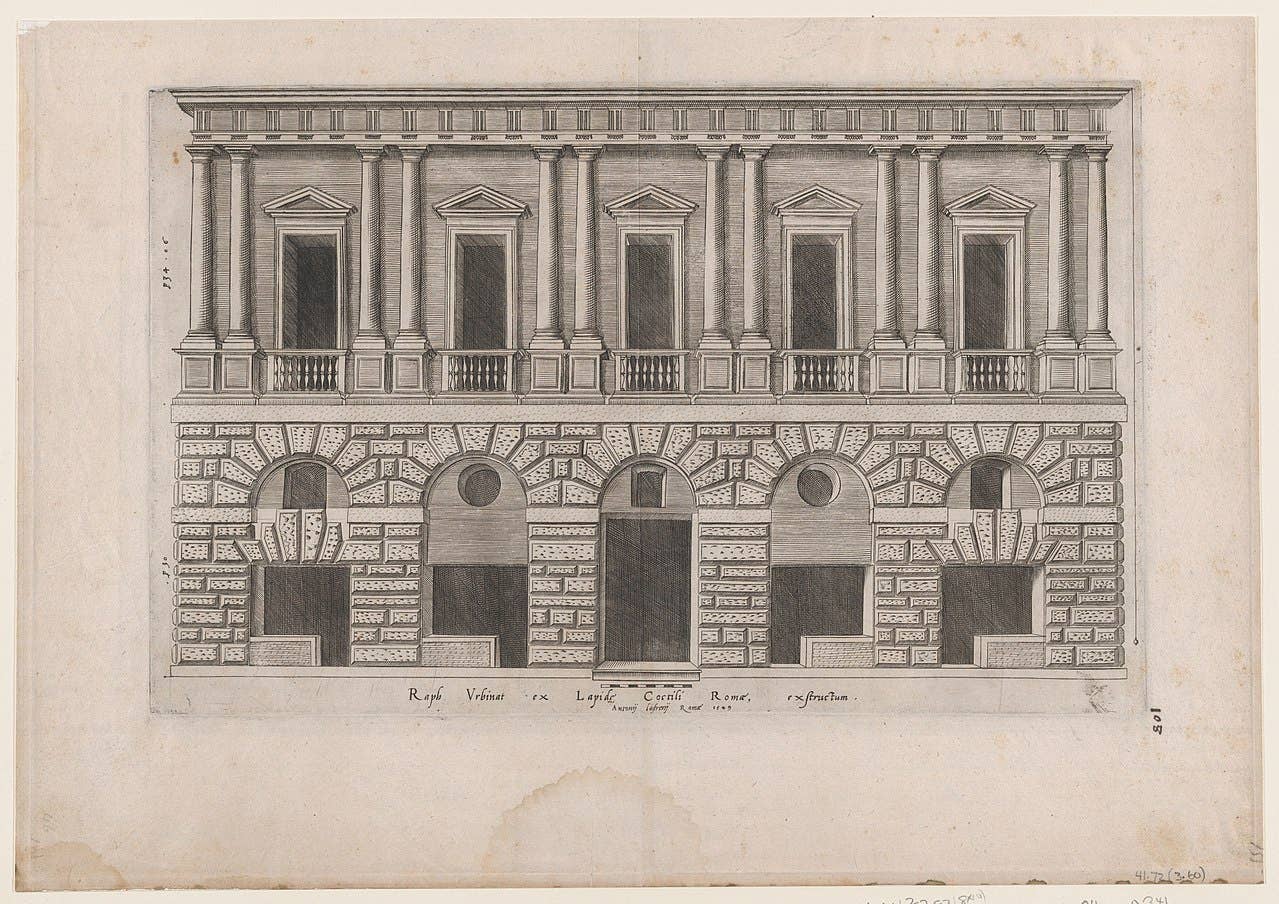

The most conspicuous pieces are the buildings, and buildings constitute architecture at a bigger scale and built over a longer span of time is urbanism.

Urbanism is built incrementally, piece by piece over time, with tradition guiding but not dictating the result. Building incrementally allows us to adjust to change, which is inevitable and constant in our lives. Sometimes change is slow and hardly noticed, and sometimes, especially in our modern age, it is rapid, which makes tradition’s guidance and innovation’s adaptions of tradition even more important in maintaining continuity and vitality in a city’s urbanism.

Yes-but methods have been a constant in classical architecture and urbanism, a term that includes various gothic and romantic variants. Using incremental change connects us with the traditions that we value, which in our nation reaches back to its ancient roots, its English heritage, and its own history, all of which is visible in our buildings and the urbanism they dominate.

For example, we can see the predecessors for common traditional American houses that are built even today in the temples of the ancient Greeks. Allan Greenberg reminds us that temple-fronted houses, even if their entrance porches are abbreviated temples, tell us that the importance of American citizens in our cities is like that of the gods in the ancient polis.

The change from gods to citizens happened step by step, and so did the architecture of the temples that have been built to serve and honor their builders. In every step the precedents remained visible and retained the role of expressing the authority of the activities the buildings served. The temples, like the gods they housed, dominated the ancient city.

In our democratic republic the long stream of yes-but innovations in the architecture of those ancient temples allows our buildings to express the complexity of our civil order where liberty and authority are served in single family houses, schools, churches, court houses, city halls and capitols and also in the banks, railroad stations and other commercial activities that serve other civil activities.

Imports, whether people or ideas or ways of addressing the yes-but method, have been especially important in enriching our nation and our urbanism. Medieval Europe villages are here, and so are rural England, the neat streets of London and Bath, and the treasured varieties of other sources and our own inventions. A century or more ago when we began reforming our distressed urbanism, we inserted grand civic buildings that emulated what the French had adapted from what ancient and modern Romans had imported from their Greek instructors and adapted to their uses.

The first colonists planted towns and cities on land that they thought of as void of civilization.

They and other plantings grew incrementally and at both an increasing rate of speed and with a larger reach but with ever less grace. The pleasant, older residential neighborhoods that we value were platted with lots that were sold separately or in small numbers and were then built on, sometimes quite quickly, by people, often of varying incomes, and always with innovations and diversity that gave a freshness to good urbanism’s traditional “look.” The result honored variety within tradition and expressed the diverse individuality of people and activities in a community.

To retain the qualities of the architecture and urbanism that serve and express our quest for liberty and justice requires continued attention to the reciprocity between tradition and innovation in incremental changes. Too much, too big, too different and too quickly are as destructive to the urbanism serving the good city as radical revolution is to the civil order, as Jane Jacobs reminded us. Radical interventions rupture a community’s social and economic traditions and offer no compensating innovations. And misguided and ill-informed modifications to buildings and the insertion of new ones can, bit by bit, erode what is valued to the point that the pieces, and certainly not the whole, have any lasting value anymore.

After all, who visits sprawl for the pleasure of being there? Who does not miss the rural areas that are “developed” with curvy streets, landscaping and minor variations in standard-plan houses intended for the same income populace? Why not build a new version of the traditional town, village or neighborhood that earlier, incremental practices produced?

Incremental change has been a constant in architecture and urbanism, and it has always served engineering and technology. The Thunderbird did not follow immediately after the Model T. Medicine and economics, and farther afield in ecology and education, the value of incremental change compared to radical intervention is becoming increasing clear.

And so has the value of traditional building, whose other name is incremental change. Tradition lets us protect what is precious as we adapt what we build to the changes that, like the weather, are unpredictable in the short term but inevitable in the long term, and like the weather is every bit as essential and unavoidable in our lives.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.