Carroll William Westfall

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Death of Urbanism

Note: This text is adapted from “Two Architects and Their Cities: Marshall and Wright,” presented at The Benjamin Marshall Society Symposium “Mansions in the Sky: Chicago Apartments between the Wars,” Chicago Cultural Center, November 21, 2017. For a YouTube version of the entire paper see http://cantv.org/watch-now/mansions-in-the-sky-chicago-apartments-between-the-wars/ between 18:08 or so and 30:38. Other presentations in this cablecast are also worth reviewing.

The city is the most important thing people build. We strive to build the good city to enable us to live the civil life that assists all of us to enjoy our natural rights and pursue our happiness, to use the words of 1776.

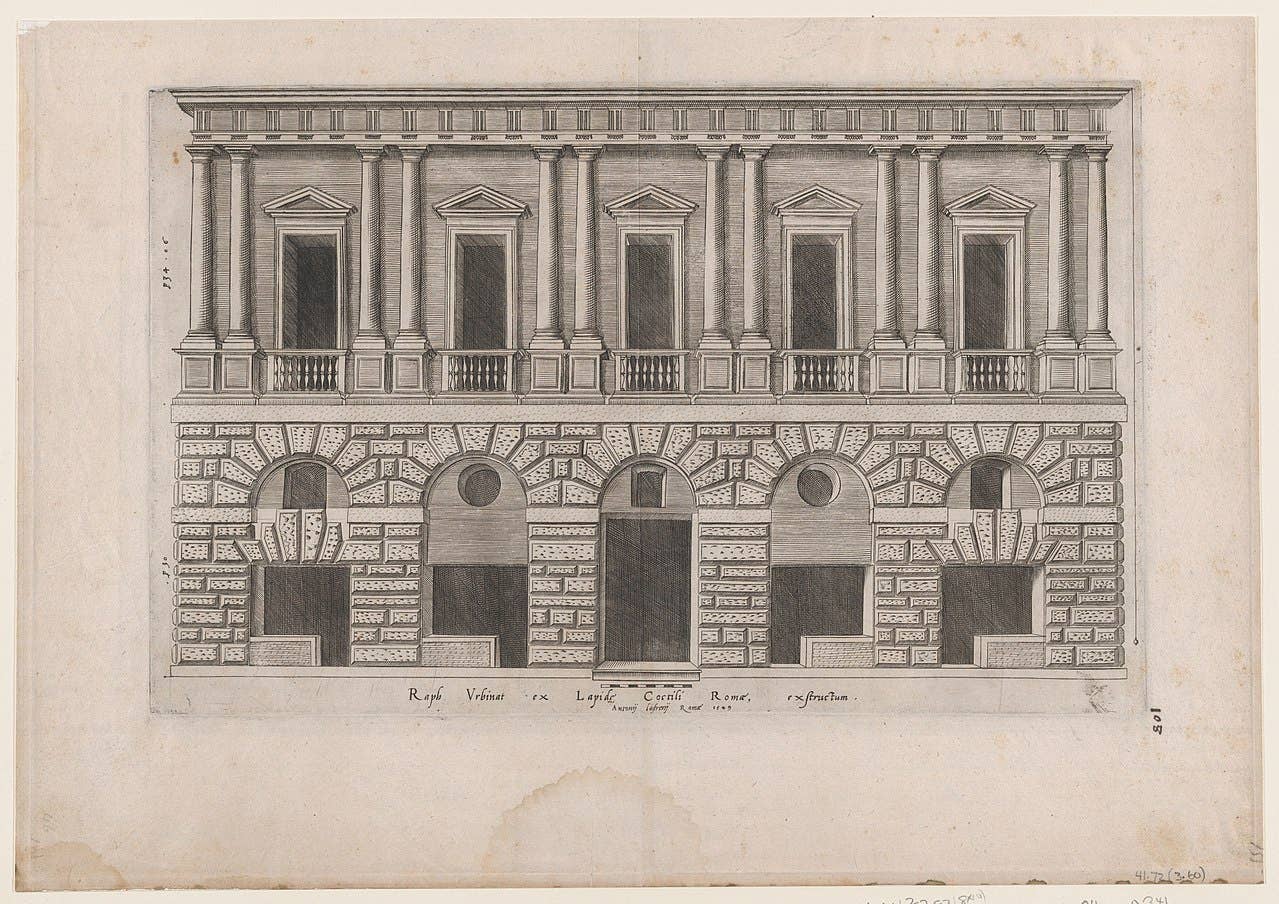

At the center of the good city is the commons where people come to know the character of others. This knowledge requires more than the casual, occasional and superficial encounters that suburbs, and now increasingly cities, offer. A commons can have any number of forms. The most familiar now is a street where people intermingle framed by a variety of residential, commercial and institutional buildings at the center of a neighborhood or town and where diverse individuals feel at home. Traditional architecture and urbanism has always provided the guidance necessary to build a commons.

Today’s new buildings fail to make the commons for the urbanism that allows the good city to thrive. There are many causes for this, but here I point to only one: the lust for fame that architects have and public adulation fulfills. America’s most famous architect was Frank Lloyd Wright who became the model for his successors. Today’s Wright is another Frank, Frank Gehry, whose renown, like that of the earlier Frank, comes from his novel designs that are the farthest remove from anything traditional, that present each building as an isolated, unique, and novel work of art, and disrupt the urbanism that serves and expresses civility.

Wright’s disdain for the city is well known. He never really escaped his early childhood in the rural Wisconsin fictionalized in Little House on the Prairie by another Wisconsin native, Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Examples of Frank Lloyd Wright's Homes

Wright’s early, suburban Oak Park home was an original interpretation of current styles, but his fame began with inventive houses for artistically inclined middle class suburbanites. These early houses belong in two categories.

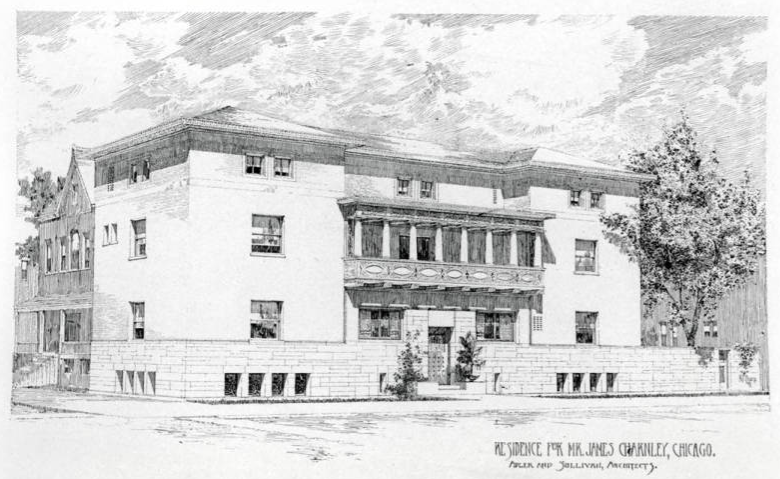

One category treats the house as a formal composition. The Charnley and Winslow Houses are examples. Their entrances are prominent parts of a geometric composition rather than examples of architectural penetration leading to an interior beyond an exterior, public façade and tectonic wall. The façade’s character seems to say: This is first of all art and only secondarily a house offering shelter.

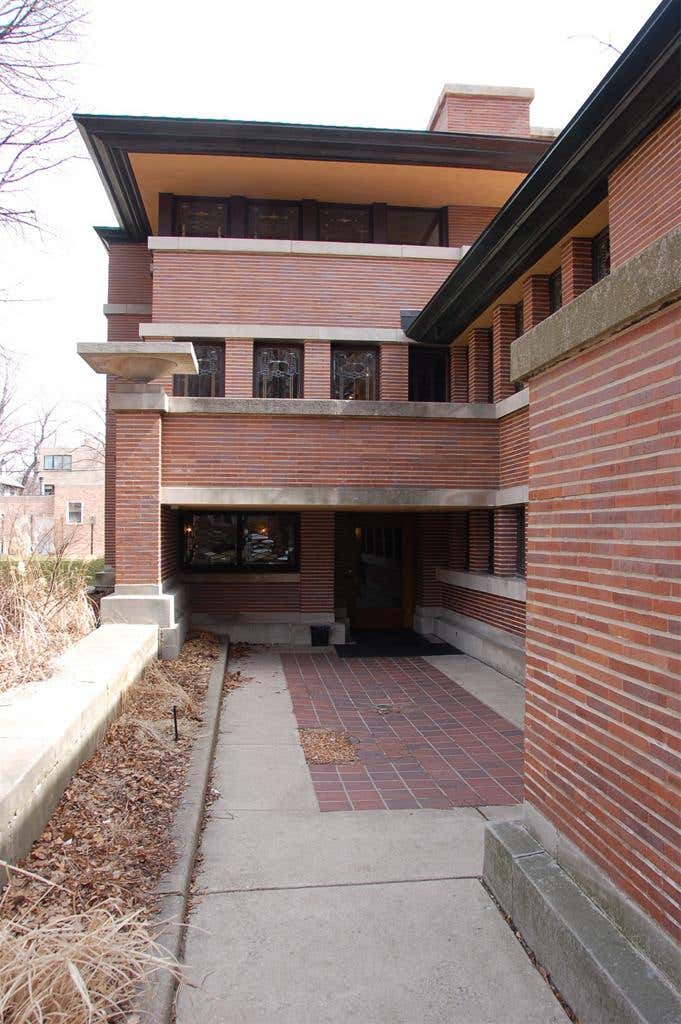

The other category is a cave-like shelter. This already appeared at the studio portion of the Oak Park home and studio, and it became a marked feature of the Robie House in Chicago. To get inside you seek out the secret passage and sneak in through a tunnel. Similarly, across the broad lawn of Oak Park the Heurtley house presents barriers and defenses as if to say: visitors are not welcome.

Wright’s houses defy urbanism. Like paperweights, they could be just as well in one place as another, something people inadvertently recognize when they rarely photograph a Wright house set amidst its neighbors. In vegetation, yes, but other houses, no.

Consider Wright’s best known house, Falling Water. Immersed in the landscape of the Pennsylvania hills, the wealth from Pittsburg’s mercantile houses made it possible. The character of this rural retreat is in its being an idiosyncratic art object and alien intruder into its setting. Wright also made contrast the principal content in his few urban buildings.

We see it in The Morris China Shop’s blank wall in San Francisco, while the china chop’s giant enlargement in New York proclaims, “I am the only thing that counts in this city.”

Wright eventually came to present himself as the successor of Thomas Jefferson. When 95% of Americans lived in rural areas the future president wrote, “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people, whose breasts He has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. … Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example.”

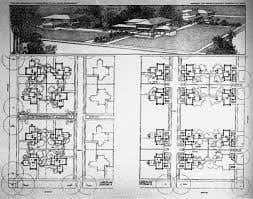

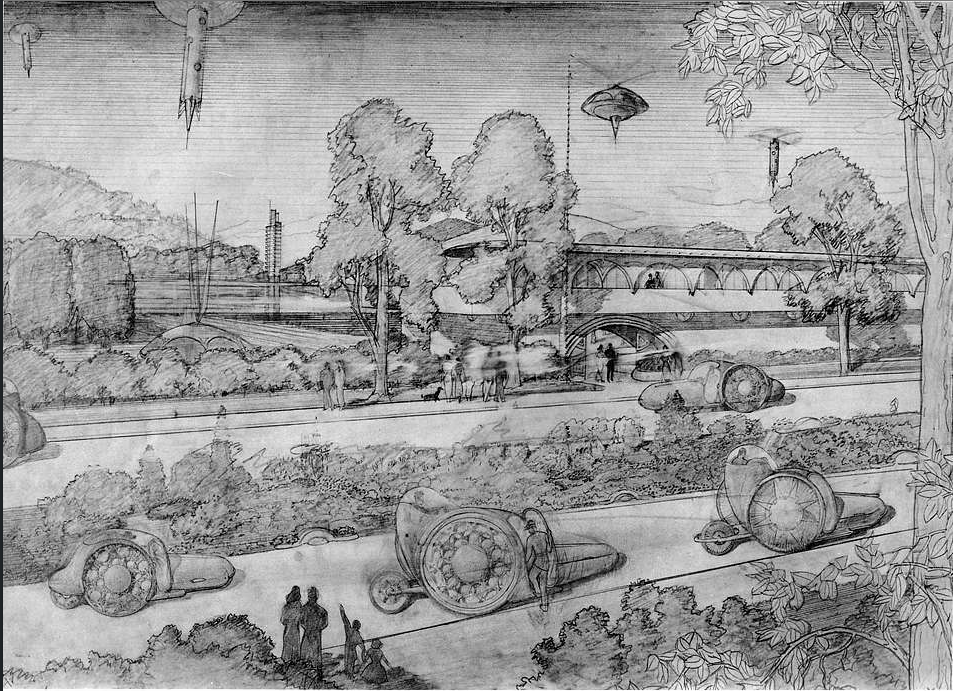

In the 1930s the census bureau found the number of rural Americans had fallen to 44% Wright imagined Americans living in Broadacre City. He would isolate each family in a little prairie house on the prairie, and from it the man of the house would go forth to work while his happy homemaker wife stayed busy at home.

Fulfilling Wright’s 1930s image were Levittowns and its ubiquitous successors. They offered the single family house his publicity had made desirable sitting on its own land that together fulfilled the post-World War II American dream.

Now add the architecture profession’s zeal to adopt Central Europe’s invention of a new architecture for a new age. An early icon for architects was the 1946 Farnsworth House, Mies van der Rohe’s reduction of the prairie house to beinehe nichts, an oxymoronic machine-made hand-crafted object set onto nature and valued for offering less, not more.

Architects now became preoccupied with creating one-off buildings-as-art-objects or to encasing urban residents and commercial activities within industry-produced wrappers rising ever taller in the cores of cities. Meanwhile, out beyond the older cities where developers and their builders were spreading vast reaches of Levittown’s spawn across the landscape and along the arterial roadways built to service them architects were hardly involved.

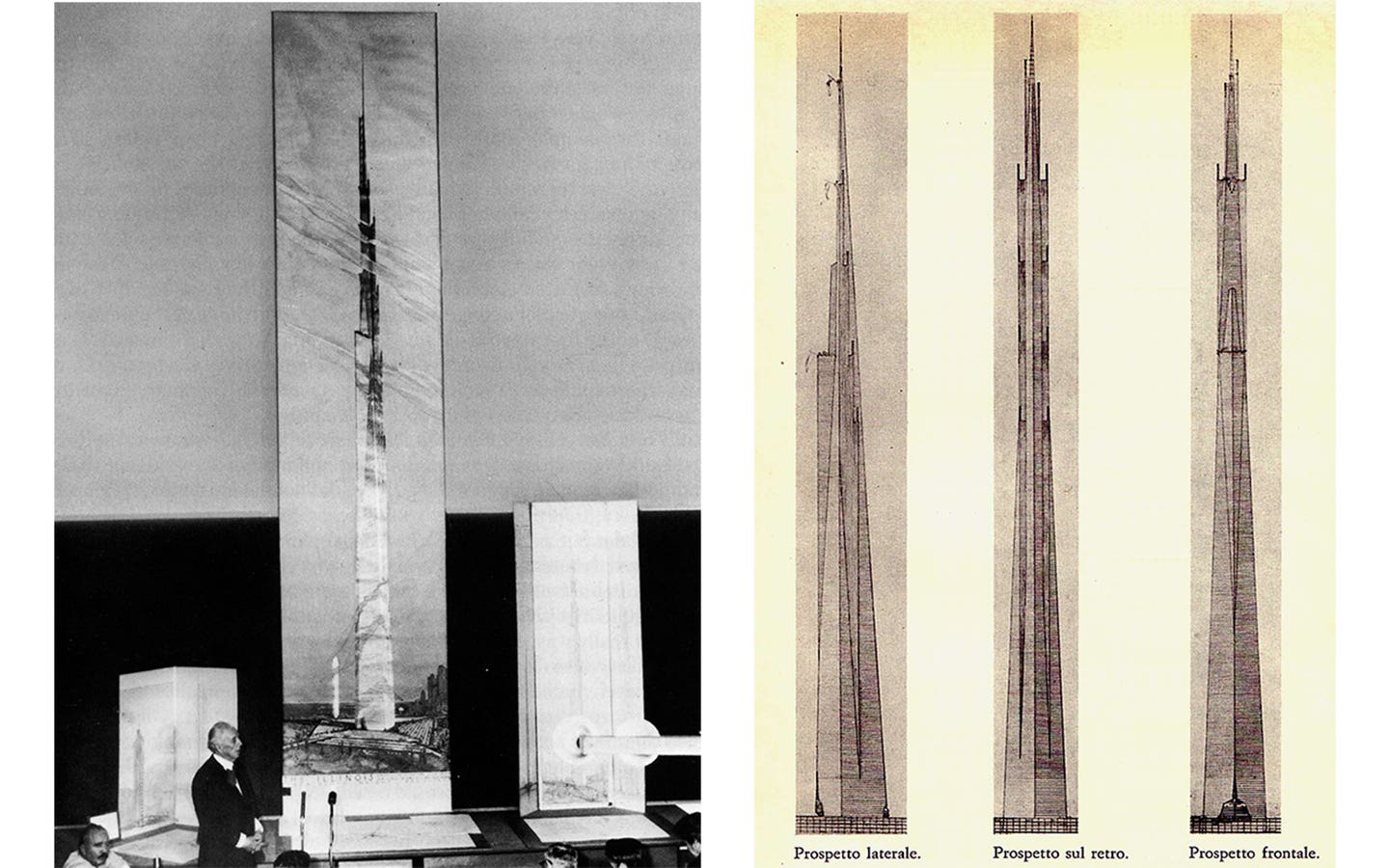

Not to be outdone, in 1956 Wright offered “The Illinois,” a mile high building on the Chicago lakefront. "In it, will be consolidated all government offices now scattered around Chicago," he said, with 100,000 or 130,000 people (sources vary), 15,000 cars, and 150 (or 100) helicopters. Again Wright was predictive, now of the anti-urban sky-thrusting towers that would accumulate in city centers. The fame that Wright had enjoyed became the brass ring that later architects would seek to grab with egocentric novelty latched to technological finesse as beauty’s surrogate while doing the bidding of the commercial interests that took charge of building in cities.

The result is our degraded commons composed of a clutter of buildings expressing narcissistic exhibitionism, many of them mansion-buildings whose multimillion dollar apartments are rarely inhabited, set against a dreary background of commercial and residential buildings sheltering workers or residents in glitzy or more often merely shabby isolation. The centers of metropolitan areas are increasingly offering only suburban ennui that alienates people from the interactions necessary to do civilization’s work.

Traditional architecture and urbanism are required to support civility, and they have begun to make headway against the practices that would destroy it. People, especially the young, have begun to inhabit or work within refitted older commercial or industrial buildings and new ones worthy of filling urbanism’s holes. Some newly built areas are seeking the mixture of uses and patterns that traditionally hosted and promoted civility. And streets that are first of all neighborhood commons are again being built.

Models worthy of guiding this practice are found throughout surviving portions of American urbanism. Even up to 1930 as the size of all urban components expanded, their scale relative to one another, their mixture, and traditional compositions and forms continued to serve and express civility. The qualities of good, traditional American commons that can guide future development survive in central areas of America’s major cities from San Francesco through Chicago to New York and in their outlying neighborhoods and suburban towns and in farther out cities like Fresno, Springfield, and Syracuse, wherever tradition guided development.

These models give the lie to the current, dominant practices that see novelty and economy as the crowning virtues of urbanism. Tradition is as strong as what people choose to draw from it. It has the power to turn the tables on misguided practices, a point that has been made from time to time in tradition’s lively history over the last 2500 years. Let tradition set things right again.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

For over two decades we have been bending and shaping iron for distinctive gates, decor, fences and railings.