Carroll William Westfall

Buildings in our Form and Figure

Traditional buildings always allude to the form and figure of man. Vitruvius said as much 2000 years ago, and innumerable images have been drawn to make that point. A familiar one that not everyone connects to building portrays a well-shaped man fitted within a circle and a square.

This Vitruvian man, and other images based on his text, stress the several proportions that can be extracted from the human figure and used in proportioning a building.

Literal-minded commentators extract numerical ratios from Vitruvius and classical buildings, mistaking the eye for a ruler measuring dimensional ratios. Instead, it measures proportionality as it assists in assessing whether a building to look right.

This analogy between a building and pure geometric figures and proportionality has more to do with the order that we seek in our lives and in the things we build. Here we reach the very purpose of the arts of building and of architecture. Those purposes connect building to the urbanism that a civil order builds. Buildings make urbanism just as individuals make a civil order to procure protection, sustenance, and justice. Urbanism is produced over time and constantly amended with new buildings serve those ends, and it seeks to achieve its own end, which is beauty. In every tradition justice and the beautiful are modelled in the larger cosmos. It makes available the proportionate harmonies of the music of the spheres, the words in poetry and speech that stir the soul, and the peace and contentment that they eye finds in the well-made building and city.

In our country all this is embodied in our inheritance from classical antiquity and its subsequent amendments and enlargements. From our beginnings we found reciprocity between that legacy in how we govern and what we build. Like our forebearers, the classical orders that we use for our monuments resonate with the human analogy. For example, in Washington, Henry Bacon’s Doric Lincoln Memorial expresses manly strength, John Russell Pope’s nearby Jefferson Memorial uses the Ionic to refer to wisdom, the statue of Freedom atop the Capitol dome stands above a Corinthian temple front that conveys the beauty of the justice we seek through democratic self-government.

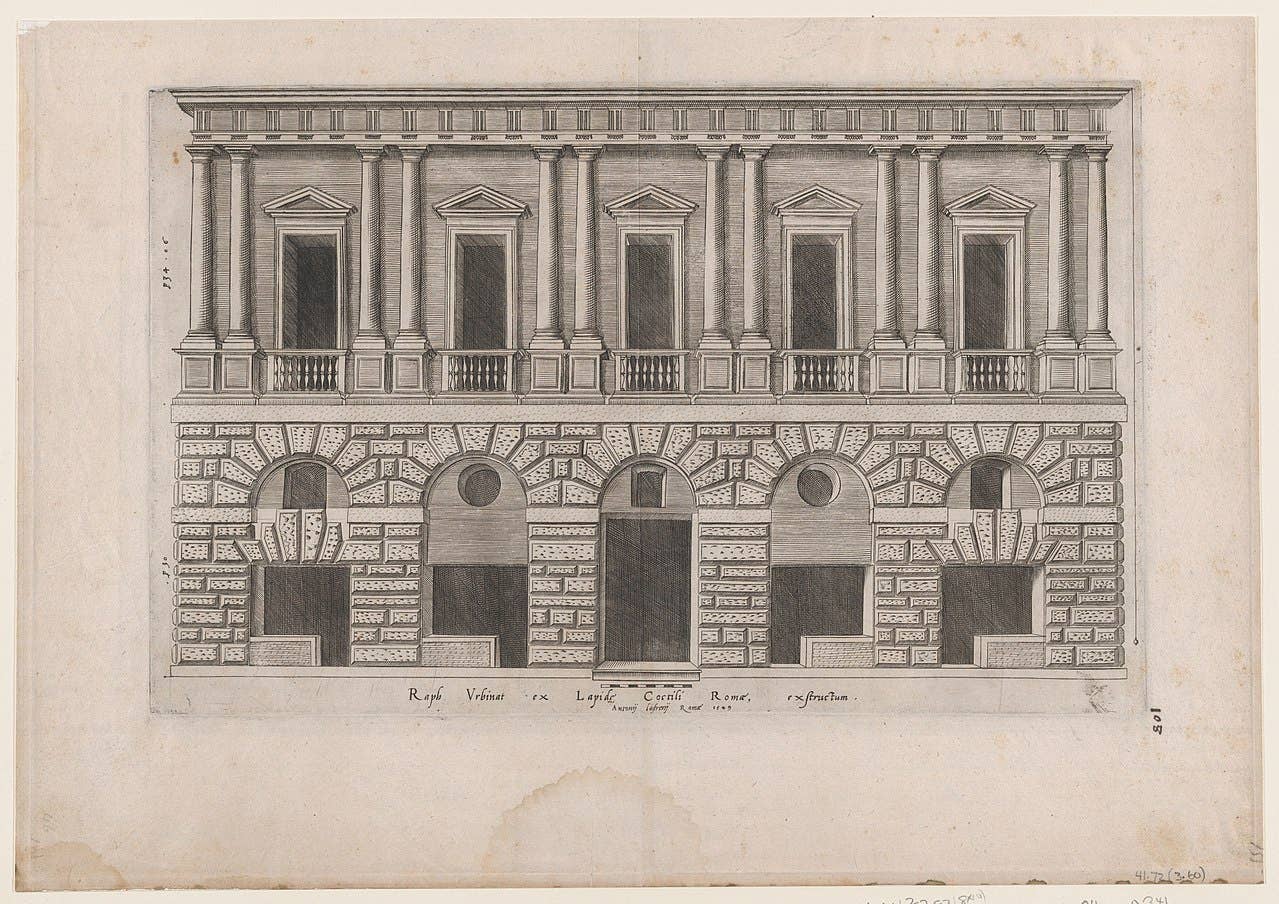

These are monuments; most buildings are not. Increasingly over the last three centuries designs have been invented to fill the graded ranks between monuments and humble background buildings--libraries, clubs, stock exchanges, banks, railroad stations, jails, poorhouses, etc. Their designs were carefully calculated to represent their status within the hierarchy of their roles in the civil orders by diluting and simplifying the designs of their superiors.

Their massing and configuration suggested their principal interior volumes, while the flexibility and variety of the classical apparatus of forms and compositions were designed to present civil faces to the public realm.

These buildings respect and acknowledge the legacy of antiquity and the successive centuries that were also bound into our democratic governance. This commonality in our civil order and civil architecture serving it made a tangible and visible expression of the filiation of institutions and the hierarchical distinctions between them. Building and urbanism serving national, state, county, and city administrations remind us of their intimate and separable relationships. When used for schools we see the role in the education in citizenship, while banks, stores, and even movie theaters display their roles in serving the common good.

Together, these buildings and the urbanism they form to serve a civil order is a testament to a dedication to the common good sought by individuals, each of them different but different in the same human way, and assembled into families neighborhoods cities, states, and a nation.

Vitruvius also told the oft-repeated story about how the first individuals worked together to make a shelter, the primitive hut, that they then improved over time to become a temple for attracting the gods’ favor. The classical temple, the best of the best that was built, would then be adapted to serve the entire rank of buildings down to their own homes, a castle or palace for a king and a humble hut for the peasant.

In a democracy, our family’s home is our castle. We build them in proximity to kin or neighbors, in neighborhoods that are particular places that from cities within the nation’s many distinctive regions.

Just as civic buildings from capitols to elementary schools often absorbed regional traits, so did Americans’ homes, even in the ranchburger end of the housing market. Their designers were seldom trained in architecture school, instead acquiring their expertise through apprenticeship and by using in their art of building what the art of architecture was producing in higher-end markets. Today we find the best continuity in regional design that complements the traditions followed by the monuments. Unfortunately, a “sore thumb house” occasionally appears to damage a cityscape, and more often a new school or churches does the damage.

These increasingly numerous blemishes in urbanism are designed by people trained in architecture school where tradition and classical are purged words.

For example, schools are receiving a program-driven design that determines the plan with an exterior enclosure given as much “design” as the budget will allow and the architect can remember from architecture school or has seen in the professional press. The inevitable result is a building seriously at odds with its neighborhood, and with an appearance that alienates it from, rather than unifies it with, the region’s buildings serving civic purposes and the homes where people live.

Not long ago there prevailed a general understanding that buildings, like citizens, were parts of a larger collective whole, with each person and building making its appropriate contribution to the common good. This was taught in civics classes and practiced by the bankers and builders and others in the culture of architecture. It was taught by architecture school instructors. And it was practiced in offices.

When this understanding was threatened, citizens resisted. In 1899, provoked by T. F. Schneider’s twelve-story Cairo Apartments built in 1894 in Washington, the Congress instituted height controls because it challenged the Capitol’s supremacy in the cityscape. In 1924 Santa Barbara, California quickly instituted a Board of Review to assure that rebuilding after that year’s devastating earthquake would maintain the city’s regional character. The next guardian was preservation. Since 1931 it has protected Charleston, South Carolina, while from Chicago to New York and in between, the loss of a treasured traditional building to build an inferior new one has been the kick-starter for preservation movements. Preservation is a poor tool for assuring continuity and promoting continued invention within tradition, especially when, if it is taught in architecture schools, it is taught as a fringe interest.

Readers of Traditional Building know that traditional classic and classical traditional designs are rarely used for the country’s major buildings, public or private. Among its most fierce (or merely benighted?) enemies are universities, courts of justice, churches, and important government agencies and cultural institutions that eagerly (or reflexively?) build the latest, flashiest, and therefore most quickly obsolete and anti-urban, self-expressive designs. Their sponsors hold the deluded, uncivil, and erroneous belief, promoted by the delf-interested fringe population of Modernists, that traditional buildings are uneconomical and unsuitable for the modern age.

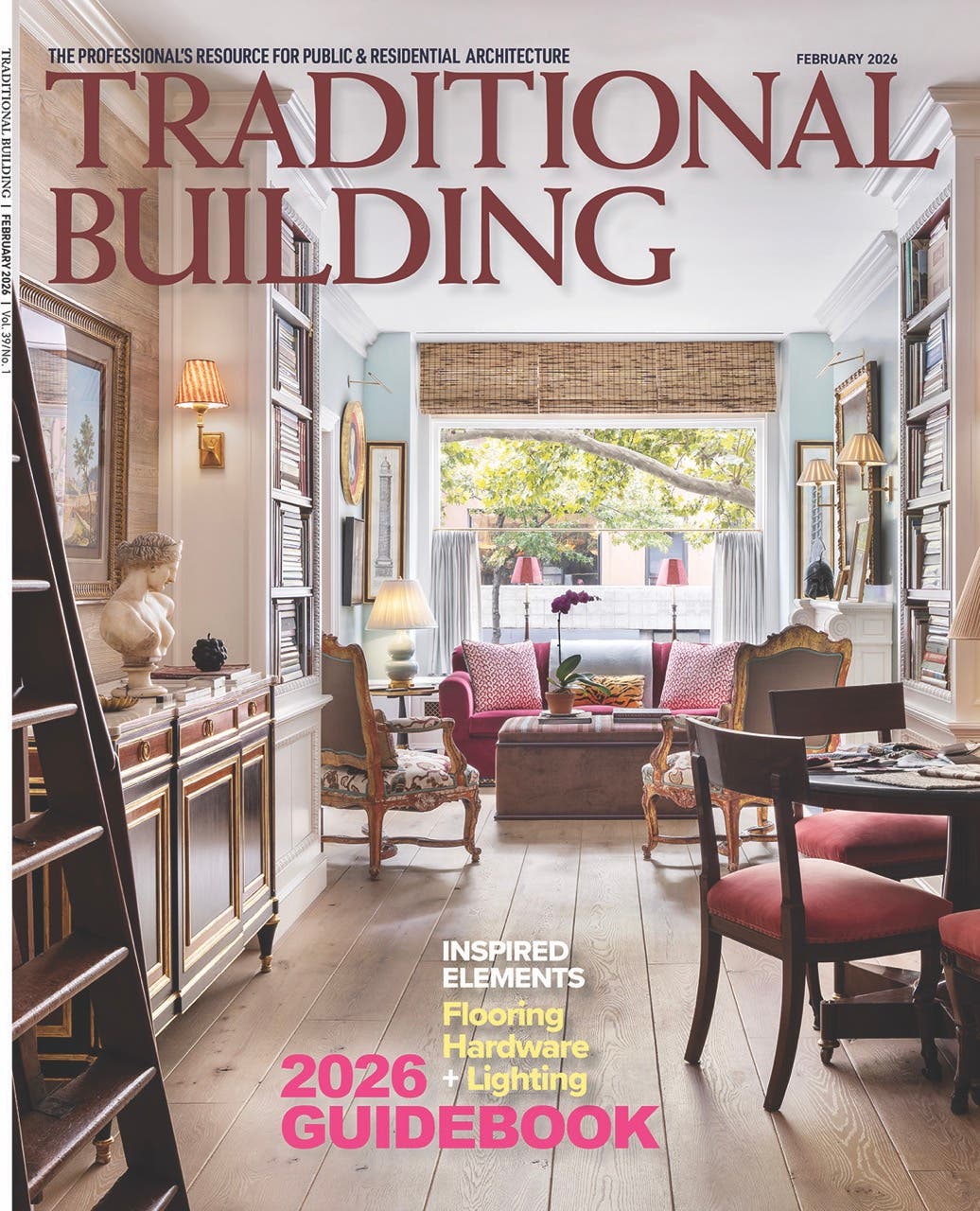

The buildings featured in Traditional Building are the residences and local private and civic cultural institutions that value traditional materials and craftsmanship, the unique beauty of a traditional design well done, and its contribution to the urbanism that holds the common good as its principal interest. They know that the brick Georgian houses we admire in Boston would not belong in Santa Fe, and the best of Santa Barbara would be as out of place as Charleston’s best would be in Santa Barbara. They admire the wide regional variations in American foursquare houses in Oak Park and Evanston, Illinois, in Fresno, California and in Richmond, Virginia. And the value, and learn from, the best of their superiors was they insert fresh, new traditional and classical buildings into the ever-renewing cityscape.

Vitruvius would see that in our present practices, the higher we go up the hierarchy of buildings, the more industrial production has come to dominate architecture. New buildings no longer allude to the form and figure of man. They no longer seek to contribute to a constantly revitalized, sustainable, and enduring urbanism serving a civil order’s common good. Instead, we illustrate the uncivil dedication of architects using their inventiveness, industry’s capacity, and misguided clients’ wishes to build not a civil architecture but something never-before-seen that before long will not be given a second look.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.