Features

Book Review: Mughal Architecture Revisited

Mughal Architecture & Gardens

by George Michell, photos by Amit Pasricha

Antique Collectors' Club, Suffolk, UK; 2011

402 pages; hardcover; 270 color photos; $89.50

ISBN 978-1-85149-670-9

Reviewed by Eve M. Kahn

A weird but enlightening fact is buried halfway through this gob-smackingly gorgeous book: Akbar was probably dyslexic. The author, the British historian George Michell, mentions this detail while describing palaces, forts, mosques and tombs that Akbar's dynasties commissioned between the 1520s and 1840s. Akbar himself, ruling from 1556 to 1605, put up buildings scattered from the Arabian Sea to the Himalayan foothills.

His roving masons carved slabs of white marble and red sandstone. His armies kept creating more potential construction sites by capturing more territory. He tracked his empire's progress in his head, since his learning disabilities rendered him borderline illiterate. "Books from his extensive library were regularly read out to him, and he is credited with a formidable memory," Michell writes.

The prose never gushes, but any less restrained writer would likely have burbled throughout this study of Mughal rulers' architectural patronage. Michell allows in only the occasional exclamation mark, and stays calm even as the New Delhi photographer Amit Pasricha's panoramic images (many in full-bleed and gatefold formats) astound.

"The northern apartment of the Jahangiri Mahal is of interest for the double-height hall with a flat ceiling partly carried on diagonal struts carved with serpentine brackets emerging from monster mouths," he writes. "Of interest," according to the surreal adjacent photo, refers to dusty red sandstone snakes soaring over part of Akbar's 1560s quarters in Agra.The text sounds only slightly awed by a 1630s room in the same Agra building. "Ceilings glitter with countless mirror pieces set into the faceted plaster vaults," the historian reports.

Michell organized the chapters geographically, one for each major Mughal capital. Some of the settlements fell into provincial torpor when the empire dissolved, while in the modern-day sprawl of Delhi and Lahore, development threatens to engulf Mughal architecture. Pasricha captured evidence of the landmarks' overbuilt or overgrown contexts and frequent poor treatment over the years. Minarets overlook ratty apartment buildings. Goats graze at the bases of ruined "pleasure pavilions" on riverbanks. Across the Yamuna River from the meticulously maintained Taj Mahal, the eroded ruin of an octagonal pool was long mistaken for the foundation of a twin domed building, a legendary "Black Taj."

Foreign armies often caused the destruction. In chronicling the fate of post-1730s Delhi, Michell lists massacres and thefts at the hands of Iranians, Afghans and maharajas. The British imposed some order in 1803, but then an 1857 native uprising "gave the English an excuse for an orgy of pillage and demolition," Michell writes. In some cases he knows where the salvage traveled next. White marble panels and columns from a vaulted bathhouse at Agra "were removed (some to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London)," he writes.

Although much documentation vanished along with the architectural salvage, Michell can still dole out background information about how structures arose and were used. (Floor plans and maps flesh out his descriptions.) He points out where animal trophies were hung on spiky towers at hunting estates, women courtiers behind screens could eavesdrop on imperial decision-making, and Akbar's successors draped fabric over poles to shelter lines of visitors at his Agra tomb.

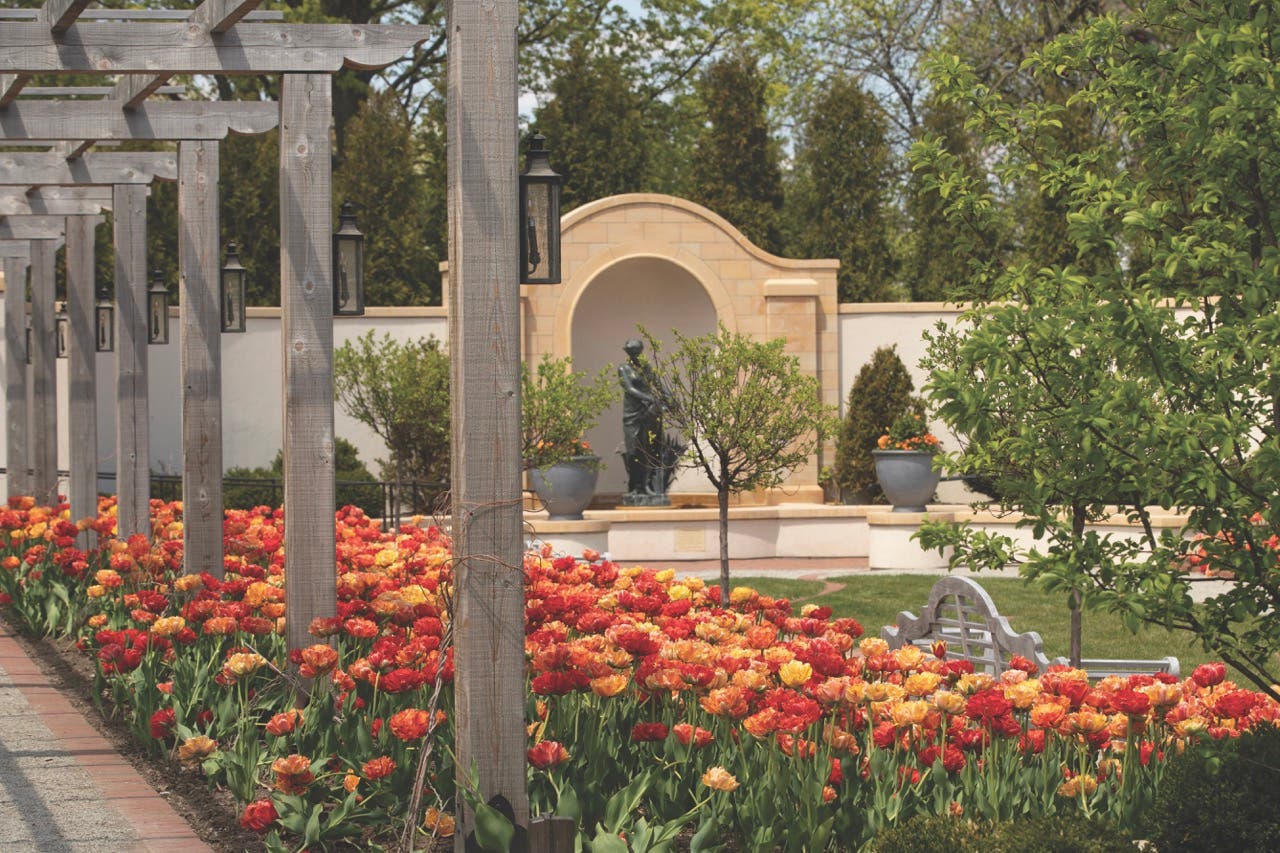

The book also explains how elaborate fountain systems on the grounds worked, as pulleys, tanks, pipes and channels fed spring water into terraces and irrigated gardens. The plantings combined Islamic and Indian horticultural traditions (orange, lemon, apple, almond, mango and date orchards) with typical Central Asian and Iranian flowers that the first Mughals would have remembered from their Uzbekistan homeland (iris, tulip, lily, rose, poppy and peony). The British, Michell adds, brought in intrusive shade trees at Mughal gardens that now "conceal rather than reveal the overall layouts."

The Mughals were confident enough in their prime to not feel threatened by foreign workers and imported design ideas.

Michell points out tapered fluted column shafts, symmetrical arabesque motifs and acanthus fronds, perhaps based on illustrations of Classical buildings in books brought in by European missionaries and dignitaries. The Mughals acquired sheets of Italian stone inlay called pietra dura, which remain installed behind the throne at Delhi's Hall of Public Audience.

The prose can bog down at times in rarefied terminology; the chhatris, chhajjas, muqarnas, pishtaqs and zenanas can require frequent trips to the book's glossary. Equally frustrating is the widespread lack of text references to particular photos. The volume seems to have started out as a coffee-table ornament, and then Michell added scholarly heft without quite coordinating words and images.

For a typical tantalizing spread, Pasricha swept his camera across a reception hall at Delhi's Red Fort, lined in floral marble inlays. The ceiling's wooden lattice is just visible, and Michell explains that its original silver plating has vanished. He also translates a line of poetry inscribed on the marble walls. It is alas nowhere in sight; the eye vainly searches for any calligraphy among the vines and petals. But the words could apply to so many rooms shown in this book: "If there be paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this!" TB