Features

Book Review: The Art of Classical Details

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

The very plain title of The Art of Classical Details belies an elaborate treasure. Fortunately, the front cover photo is beguiling and beautiful, a welcoming stairwell by Wadia Associates. This excellent new book by Phillip James Dodd offers satisfaction in a greater variety of ways than most works on architectural design would attempt, let alone achieve. It is both lovely to look at and rewarding to read. It is a pleasure to pick up and quickly browse; it is also worthwhile to study.

A variety of organizational strategies makes it possible for this to serve as an attractive coffee table book as well as a serious course in design. First, throughout most of the book, a page of handsome illustration alternates with a page of explanatory text. This rhythmic pattern is refreshing for both viewer and reader, right-brain and left.

A second prudent strategy was to divide the book into two distinct halves, the first devoted to theory and the second to practice – essays and projects. The first half is divided into contrasting parts; first, from writers and scholars, then architects, craftsmen and artisans. The result is a wonderful variety of viewpoints, all personal, thoughtful, and all contributing to a comprehensive Classical outlook. Reading through this unusual procession of personal expressions from well-known authorities on a single theme is a delight. And all of us can learn from it.

Halfway through the book we shift from theory to practice, and a long series of beautiful projects are presented with commentary by the designers. This is an excellent opportunity for the readers to draw their own conclusions about how the points of view expressed in the first half of the book are exhibited in contemporary Classical design.

Among the many outstanding essays in the first half, all of which are worth contemplation, the richest surprise for this reader was an extensive discussion of how “architecture is frozen music.” This axiom came to my attention early in my own life, and ever since then I have sought to understand the comparison, attributed then to Goethe but also to many others all the way back to Pythagoras. David Watkins summarizes this foundational concept admirably, as it has existed throughout history.

Though modest in this erudite company, the contribution of my own mentor, Henry Hope Reed, was a delightful surprise. He died just last year after a lifetime of inspiring activity urging the onset of a New American Renaissance. Dodd described him as “the foremost spokesman for the classical tradition in architecture and its allied arts. In 1968, he co-founded Classical America, the pioneering organization that promoted the current resurgence in classical and tradition design.” I am grateful to Dodd for including Reed in this compendium, thereby expanding his already considerable legacy.

Highlights

To mention only some of the highlights in this vast collection of excellent essays (50 or so) is a disservice to the rest of them, but I feel I must make note of a few that spoke most clearly to me. The first, appropriately, is the Foreword by David Easton who writes “with a nod to our past and a keen eye to our future” and deftly summarizes how this book on Classical detail relates to “the broad view of the homes we live in” and the changing culture at large.

Easton’s experience, like many of our own, ranges from a Bauhaus background, tempered by the enchantments of travel, arriving happily at a career focusing on the Classical tradition. One wistful note is inserted, “the hand and eye have a special place in this innate understanding of how to lay down detail.” He wonders if we might be losing this with CAD. I worry as well, but the Foreword ends by affirming “at least for this moment, we can all marvel at the beauty of classical detailing and be glad that it has been kept alive and well.”

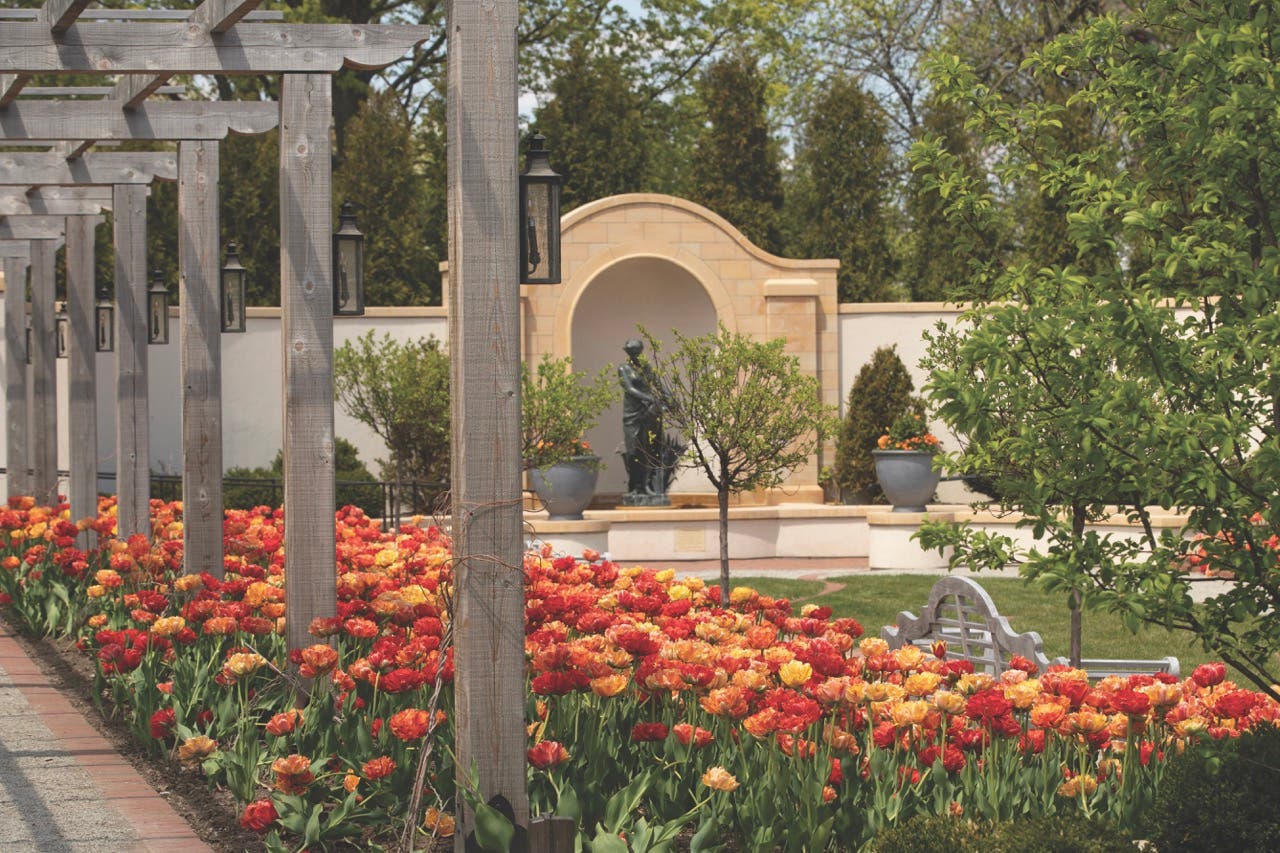

After a masterful introduction by Dodd himself, which is itself a mini-course in Classical architecture, the opening essay by Jeremy Musson makes a daring leap from the vast vision of an ancient Arcadia to any of the Classical interiors of today. He illustrates how the ideal of a harmonious, ordered and beautiful world as exemplified by Arcadia is fully expressed in the detail of a dining room fireplace by Allan Greenberg, as well as in a graceful entry hall staircase by Gil Schafer, or in a serene and simple landscape view of a contemporary Georgian home by Francis Johnson.

Midway through the book, Richard Cameron picks up the theme of the primacy of drawing, which is echoed in other essays. He makes a very persuasive argument for the merits of the Beaux Arts system of education to which he attributes much of the wonderful architecture in the early years of the 20th century in America. As a prime example, he offers the New York Public Library by Carrère and Hastings, both of whom were products of the Paris École.

A very succinct summary of the basic literature of Classical Theory is contributed by Robert Chitham from a larger work of his called “On Proportion.” The ordering principles, beginning in simplicity and zooming into splendid complexity are dramatically illustrated by a photo of the gorgeous staircase under the dome of Julian Bicknell’s well-known Henbury Hall, a project more fully detailed in several other parts of the book. An essay from Bicknell himself on the “Craft of Classical Details” enthusiastically describes the pleasures of working with skilled and knowledgeable craftsmen who happily team up to create the unified goal they all desire.

It is especially satisfying to read the many eloquent answers to so many of the accusations employed by modernists to discredit the movement toward a New American Renaissance. Hugh Petter, for instance, takes on the familiar “…of course you could not do that nowadays…” and provides ample evidence that of course we can.

Elsewhere, in rebuttal to admonition that “we must not copy,” Foster Reeve affirms that “copying from great work is probably one of the most valuable activities in developing original art.” And in a stirring conclusion to his own essay, which could serve as both introduction and finale to this whole book, Petter announces “it is time for optimism and for careful action too, to ensure that the green shoots which are emerging are carefully nurtured so that they mature into strong plants which can, in turn, embellish both current and future generations of new classical buildings with fine innovation and vigorous details of the highest quality.” And I would add: Take this book. Read. Learn. Teach.

The Art of Classical Details: History, Design, and Craftsmanship

by Phillip James Dodd; Forward by David Easton

The Images Publishing Group, Australia; 2013

256 pp; 200 color illustrations; Hardcover; $70

ISBN: 978-1864702033

Alvin Holm, AIA, is an early advocate of traditional design, in private practice since 1976, and winner of the first annual Clem Labine Award. He has lectured and taught widely, having initiated a course in Design with the Classical Orders in the National Academy of Design in 1981 and subsequently at many other institutions. He has been an ardent member of ICAA since its inception and prior to that an officer in Classical America.