Features

Appropriate Architecture for Historic Charleston, SC

The history of 404 King Street in Charleston, SC, illustrates the conflicts between Modernism and traditional design.

By David Payne

What is considered appropriate architecture for the 21st century? Is it, as the Modernists would have us believe, only architecture that represents the latest in technological trends and cutting-edge design – or is there still room for architecture rooted in tradition, yet unmistakably 21st century? The evolution of the built environment at 404 King Street in Charleston, SC, provides a case study of architecture and historic preservation theories and practice through its several centuries of existence.

The most recent building on the site, the old Charleston County Library was built in 1960 in a controversial Modernist design; it replaced a traditional building. It was recently demolished in August, 2013, to allow construction of a Classically-inspired hotel building more fitting with the character of Charleston.

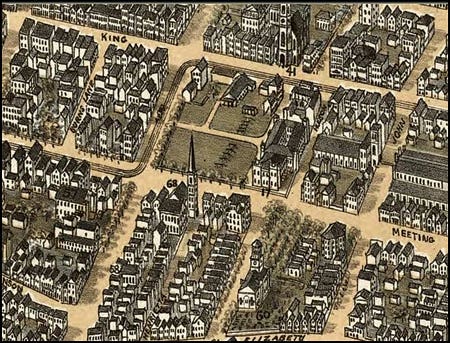

The site at 404 King Street borders Marion Square, Charleston’s major open space, on the west and has had a succession of buildings. The history of 404 King Street begins with the incorporation of the city of Charleston on August 13, 1783. At that time, land just outside of the original boundary of the city and bounded by King, Hutson, Meeting and Boundary Streets (the current site of Marion Square) was given to the city. Six years later, on August 18, 1789, the northern portion of the site, consisting of 1.5 acres and bounded by King, Hutson, Meeting and Tobacco Streets, was deeded to the Commissioners of Tobacco Inspection for the State of South Carolina to build a brick warehouse for their use. In 1822, an aborted slave uprising prompted the establishment of a city guard house where the tobacco inspection building was located.

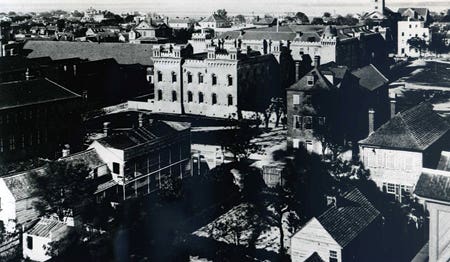

In 1829, a fortress known as The Citadel was completed by architect Frederick Wesner on the north side of Marion Square. It still stands today.

The site is most significantly associated with this building, which later evolved into the Military College of South Carolina. 404 King Street was later occupied by both the west wing of The Citadel, constructed in 1854 and rebuilt in 1889 after a fire, and a police station built in 1887 after the earthquake of 1886. Both of these buildings were torn down for the construction of the new library building in 1959.

The Original Controversy

Few architectural controversies in Charleston have reached the intensity of the fight over the design of the new Charleston County Library in the late 1950s. The controversy was especially interesting, considering that the purview of the Board of Architectural Review did not even reach this section of the city at this point in time. On April 20, 1957, the News and Courier published an editorial agreeing with the site for the new library, but arguing that the current building should be preserved. They believed that it represented a central location, accessible for all citizens, and made their position about the building very clear. The editorial stated: “Tear down the Old Citadel? No, a thousand times no!”

A later article in the Evening Post on June 2nd brought up the same issue of reuse or demolition, but seemed to begin to accept the inevitable when it commented that it hoped the new building would reflect Charleston’s architectural atmosphere. It commented that the west wing of the building was still being used as faculty quarters and the old police station was now county and public offices and that both sections were being discussed as a site for the new library.

An earlier structural report in 1947 had found that it was not economically feasible to repair the building and architect C.T. Cummings – ironically, the architect later given the commission for the new library building – was quoted as saying that the buildings could be converted to a library that “would have been considered adequate 100 years ago.”

By August of 1957, the decision to tear down the west wing of the Old Citadel and the police station had been made by the library committee, based on the recommendations of architect C.T. Cummings. He clearly preferred a new building, stating in an August 9, 1957 News and Courier editorial, “In my opinion, it would be more economical to tear the building down completely and start anew. Then you can start a new building and you’re not confined. You can’t plan well if you’re confined.”

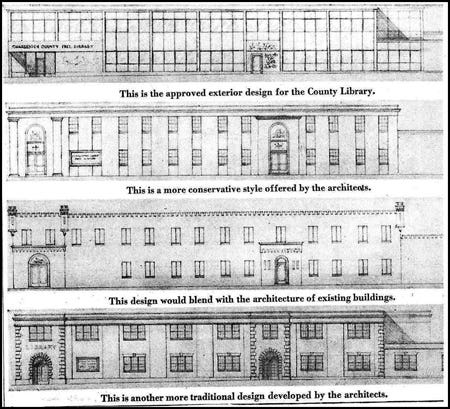

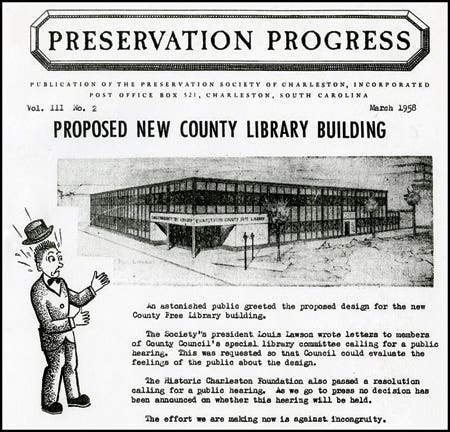

The plans and elevations prepared by the local Charleston firm of Halsey and Cummings were approved by the County Council on April 5, 1958, and they were instructed to begin preparing details and specifications. The new building was to be built of steel, concrete and masonry using curtain-wall construction. This meeting of the County Council was the first time that the plans were made available to the public – and the outcry was fierce and immediate.

Public Response

The day after the plans for the new building were revealed to the public, the Preservation Society of Charleston (PSC) immediately stated its opposition to the new design and stated that the proposed library design would not be in tune architecturally with the rest of the city. Within a week, editorials began to appear in the Charleston newspapers both for and against the new design. Anthony Harrigan wondered in a April 12, 1958 editorial in the News and Courier, “Must public buildings be glass and steel bird cages?” and “What’s so good, after all, about modernistic design that reduces home and factory, church and school, office and library to the same pattern: a flat roof, unrelieved masses of concrete, and strip windows?”

He stated that economy was not a good argument for the new building, since Charleston had always built beautiful warehouses and other utilitarian structures. While he acknowledged the need for a new library building, his opinion was that new buildings in Charleston should be modern on the interior and traditional on the exterior.

On the other hand, John Jeffries from Clemson College questioned reusing the Old Citadel building and advocated for a modern design, even though he had not even seen the proposed design. He felt that designing new buildings in old styles devalues the existing historic architecture and that the historic and modern provide a contrast that highlights each of them. In an argument that sounds like it could apply as equally to the current controversy in Charleston regarding Clemson’s proposed new architecture building, Jeffries commented in a April 14, 1958 editorial “Why should we pass up the opportunity to be the 20th century and return to one that can never return?”

The PSC and the Historic Charleston Foundation (HCF) asked for another public hearing on the design in order to gauge public opinion on it. The County Council agreed to a meeting where the design of the new library could be debated by the public in an open forum and this took place in March, 1958. While there was a brisk debate on the design of the new library, no change to it was made by the County Council.

This decision, however, did not prevent citizens from continuing to express their opinions on the design. Editorials continued to appear in the Charleston newspapers up until the time when construction actually started. Additionally, there was no lack of alternative designs proposed by the architects selected for the job, as well as others.

The PSC did not feel that the County Council was expressing the will of the citizens of Charleston in building the new, Modernistic library design and disagreed again with the County Council’s points. Their position seemed to be supported by a straw poll conducted by the Evening Post in November of 1958 that found that of 2,099 votes casts, 1,787 (85%) were against the Modern design. The County Council responded that changing the design at this stage would be costly and unfeasible. The library building finally opened to the public on November 26, 1960, with 75,000 books and a modern mechanical system. By the mid-1980s, however, the library system was determined to be inadequate for the county and voters passed a referendum committing $15.75 million to build new library buildings.

Initially, the plan was to add the additional floor to the existing library building at 404 King Street, but it was determined that the building could not survive an earthquake with the additional third floor. Mayor Joseph Riley of Charleston suggested that land be purchased on Calhoun Street for a new library, construction of which was to begin in the fall of 1994 and last two years. The once-controversial library at 404 King Street was to be sold to a private developer and demolished. That sale occurred on March 15, 1995, although the library continued to occupy the site until April 8, 1998, when it finally closed for good.

While referred to as undistinguished by some, the new library building at 68 Calhoun Street was praised in 1998 by Post and Courier architecture critic Robert Behre that its grandeur could more easily be seen by comparing it to the old building. Commenting on the old building, he noted in a March 30th, 1998 story: “Widely loathed, the old library’s most luxurious feature – pink marble siding – became obscured by a black ooze seeping from the aluminum window frames. It looks like the Blob is working away on the inside.”

Return to Classicism

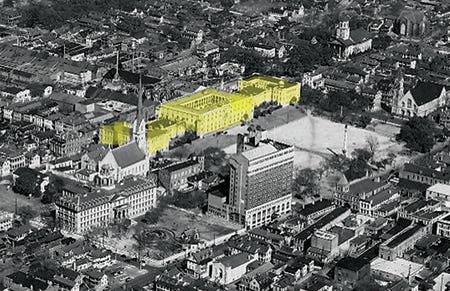

Articles discussing the future of Marion Square treated 404 King Street as if it were already a foregone conclusion that the building would be demolished. A conceptual project in 2003 sponsored by the Committee to Save the City, which advocated a return to Classical architecture that was more appropriate for Charleston, showed a series of new buildings around Marion Square. One of these new buildings, based on the architecture of the Old Citadel and including a 10-story-tower, replaced the library building.

The first actual plan to demolish the building was put forward by the owners, Bennett Hofford Construction, in early 2004. Their plans called for the demolition of the existing building and construction of a new, eight-story, $35-million hotel that would contain 185 rooms. The plan received unanimous approval from the Board of Zoning Appeals and widespread approval from the community, although there was some concern expressed at the number of rooms. Bennett Hofford announced its intention to demolish the old Charleston County Library building by 2005 and open the new hotel by 2006.

After zoning approval, the next step was to bring it before the Board of Architectural Review (BAR) for conceptual approval. The BAR would also have to approve the demolition of the existing library building. Despite the criticism from preservationists, including the PSC and the HCF, that the new building was too tall, the hotel proposal was given BAR conceptual approval based on the height, scale and mass of the new building on December 14, 2005. The next step was to get a height variance although, at 104 ft., the new building would still be shorter than nearby buildings, including the Federal Building at 113 ft., the Francis Marion Hotel at 165 ft., and the steeple of St. Matthew’s at 297 ft.

To some degree, the hotel proposal brought out many of the same issues that the design of the library did 50 years previously. Citizens were concerned that the construction of such a large building in historic downtown Charleston would ruin the historic character and set a dangerous precedent.

Interestingly, there seems to be no evidence to show that anyone was particularly interested in preserving the old Charleston County Library building at this point, despite the fact that it was nearing the 50-year cutoff to be considered eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. An editorial in the September 11, 2010 edition of the Post and Courier stated: “It’s unlikely that many people want the derelict former Charleston County Library building to stay at 404 King Street. And it appears that most do not object to a hotel taking its place.” On April 20, 2008, the BAR granted preliminary approval to the project by a 5-1 vote.

At that point, the demolition of the old library building and construction of the new hotel was being delayed by lawsuits regarding the zoning approvals that were given to the project. Although the Charleston Planning Commission, the BAR and the Charleston City Council had all approved zoning variances, the PSC and the HCF sued the city, claiming that the parcel was illegally spot-zoned. Reversing a lower court decision, the SC State Supreme Court issued a ruling on October 17, 2012 allowing the hotel project to proceed.

Aside from being used temporarily as a haunted house in the late 1990s, the old Charleston County Library building had been vacant for at least 10 years. The first mention of any interest in preserving the building came from the PSC, which announced its second annual “Seven to Save” list on May 10, 2012. The second item on the list was Mid-century Modern Architecture, which was described as “controversial and misunderstood.” The old library building was one of the specific examples of this period mentioned as deserving of recognition and protection. Despite this publicity, the old Charleston County Library was torn down in August of 2013 and the site is currently awaiting construction of the new hotel building.

Context vs. Architectural Fashion

The old Charleston County Library building is a prime example of ignoring the existing context and building to suit the immediate architectural fashion. Since the building was completed, traditional architecture has begun to make a comeback, partially as building more sustainably has become an important focus. Preservation cannot continue to work against the tradition that built the buildings that the movement preserved in the first place. And it cannot prevent the current generation from constructing buildings that future generations will want to preserve – unlike the vast majority of buildings that are being built now early in the 21st century.

Due to the flaws in its ideological background, historic preservation is attempting to further separate contemporary practice from architectural tradition. While tradition is a living thing that changes and adapts over time, historic preservation seeks to capture a moment in time rather than perpetuating the tradition that created that moment in the first place. One of the issues with current preservation policies is that they were developed during a completely different architectural culture. The guidelines are ambiguous and meant to prevent uninformed and sloppy traditional architecture. However, the preservation standards have not kept up with the recent interest and growth in knowledge of traditional architecture.

The recent history of 404 King Street provides numerous lessons for the theory and practice of architecture and historic preservation in the 21st century. While the historic preservation movement has been enormously successful in preserving both individual buildings and historic districts in the United States, its philosophy, policy and practice have struggled to incorporate Modern buildings. The Modern movement emphasized a complete break from the past and produced buildings that, in some cases, replaced historic buildings that early preservationists fought vainly to save.

In short, current preservation philosophy is advocating for the preservation of existing buildings like the old Charleston County library that contradict the original aims of the movement and hamper efforts to build new buildings like the new hotel at 404 King Street that are more similar to buildings that inspired preservationists in the first place and more likely to be treasured landmarks in the future.

David Payne is a Professor of Architecture and Design at the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, and an adjunct faculty member at the College of Charleston. He holds master’s degrees in Historic Preservation from the University of Vermont and Architecture from the University of Miami. He recently completed his doctoral degree in the Planning, Design, and the Built Environment program at Clemson University and his dissertation was entitled Charleston Contradictions: A Case Study of Historic Preservation Theories and Policies. His research interests include the impact of Modern architecture on historic preservation and the role of traditional architecture in the 21st century.

Custom fabricator & installer of architectural cladding systems: columns, capitals, balustrades, commercial building façades & storefronts; natural stone, tile & terra cotta; commercial, institutional & religious buildings.